Instinct is often spoken about by artists but it is not the same kind of animal instinct that allows birds to fly backwards and forwards across the globe or any other instinctive behaviour of animals. Artists’ instincts are largely composed of memories of art, or of life itself. We all have memories of life, whether we are artists or not, it is this allows communication to take place. An artist’s instinct is cultural rather than genuinely instinctive. It seems instinctive only in the sense that it is learnt through vision not through rational, verbal communication. Much of the judgement made by artists under the banner of ‘instinct’ is built-in cultural preference.

Where this instinct comes in for artists is the use of the 5000 year old language of form, which is mainly inherited and cannot be sensibly expanded without cause. Artists often speak of standing on the shoulders of masters, that is because we have a history, not remotely that art historians convey. Art history for artists should be taught by artists. The art historians version is for consumers and mostly like Rembrandt scholarship, grossly misleading. Considering I pointed out the failures in my article in The Burlington Feb.1977. One has to be extra generous to overlook the criminal mis-information that is still taught in high places.

I have written a lot about the alternative tradition because on the whole it is neglected. It is based on Roman geometry, which developed as a result of making copies of terracotta portraits or Greek sculpture. It is a three dimensional geometry, developed from a measuring boss on the sculpture itself that leads the mind of the artist towards the Platonic solids, resulting in a more accurate description of the visible world. It is present in the major works of Masaccio, Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas, Giacometti and many lesser names. Rome has had a bad press since Wincklemann but if you understand my point about these artists you will see that the bad press is horribly undeserved. My discovery that the most revered works on The Parthenon are in fact Roman restorations adds considerable weight to this argument. See link to A Sculptor’s Perspective.

The two traditions of form, the Greek and the Roman have dominated western art. The modern obsession with originality, that is in truth no more than novelty, is actually undermining the time-honoured visual language, which was used for telling religious stories also to the illiterate. The arts of drama and dance contribute alongside sculpture, painting and drawing to the refinement of that language. It was universally comprehensible because it was the same body-language that teaches us to navigate life itself. Art cannot tell valuable stories without the human body. “History Painting” as it was called, was once regarded as the highest form of art and should remain so; the rest is decorative, life-enhancing maybe but not central to human cooperative existence.

What I am saying is that all these arts had a beneficial effect on human communication that has been neglected by the modern preference for abstraction in the arts. This has done incalculable damage to inter-human understanding. Our universal, non-verbal communication is obviously in steep decline.

Prepare for the massive changes in art history that will result from recent discoveries

by studying with Nigel Konstam at Verrocchio

“Verrocchio” at the Strozzi Palace is a important exhibition because it sets Verrocchio in his artistic tradition – his antecedents as well as his influence on future generations. Vasari describes him as having “a somewhat hard, crude manner” which is not untrue by the standards of Vasari’s day but I would choose much more positive words such as classic, Roman, geometric, observant. Phrases like a meticulous delight in the volumes of nature, dedicated to visual truths, a great draughtsman. Verrocchio was trained as a goldsmith working on a small scale but his ambition grew in scale when in Rome fairly late. He had the misfortune to mature in the long shadow of Donatello and his reputation was later over-shadowed by his star pupil Leonardo da Vinci. But as a teacher he also had many other famous names as his students or followers.

As far as I’m concerned I would reverse the usual judgement and say that Leonardo’s greatest work, his curiosity and inventiveness was strongly influenced by Verrocchhio. There are very obvious influences and habits in common, both loved drawing complicated hair arrangements, both had a wide curiosity about natural appearances, about anatomy, about landscape and most of all about natural forces and how to master them. Both would leave works for a long time and come back to them with a fresh eye perhaps after years. Both found it difficult to finish their work to order.

Verrocchhio died while casting his great final masterpiece The Colleoni Monument in Venice; he was only 50. The great importance of Verroocchio is the seriousness and dedication with which he pursued the physical three dimensional likeness of his subject matter he was a great teacher and a great artist. Sadly the present catalogue follows the normal approach by calling the exhibition “Verrrocchio, Masterr of Leonardo”. This is a shame. The catalogue spends half a page trying to persuade us that his nick-name Verrocchio means winch rather than true eye, which is so much more appropriate. Added to which some of his most impressive works have been attributed to other masters: The portrait of his major patron Lorenzo the Magnificent (still in Washhington) is attributed to an imitator but what a magnificent job the ‘imitator’ made of it – infinitely better than the master himself in his portrait of Piero Medici (included in the exhibition), which is a fairly run of the mill production in a great age of portraiture; while the Lorenzo must be one of the greatest portrait busts ever made. The terracotta putto, an obvious by-product of the equally beautiful “Winged Boy with Dolphin”is attributed to an anonymous student though it has all the hallmarks of the master himself. The high quality of his workshop is well represented.

In spite of these minor disadvantages the exhibition is a wonderful opportunity to re-evaluate a major master, presently undervalued, and to follow the methods of instruction of the leader of the greatest art school ever known. The catalogue admits “he shaped the style and taste of the age of Lorenzo the Magnificent like no other” what more need be said.

–

There is still plenty of figurative art being done today but we never see or hear of it in the media. It has been eclipsed perhaps because no one writing about art now has the experience to look at it and make sensible judgments about it. As observation has been the main stay of art for the previous 40,000 years we are clearly living through a long hiccup in a major and important field of human activity. Why?

As a student I subscribed to the growing interest in abstraction. Art seemed to be returning to an area that had fallen into neglect in the late 19thC. Brancusi and Picasso seemed to be reconnecting with an element in primitive art that demonstrates the abstract nature of thought resulting from the triumph of word and number. Human knowledge is transmissible and can therefore develop through time as a result of these abstract systems. That said, art is one of the few areas where we can confront and compare nature with what we think we see; we are often surprised. I see observed art as constructing bridges between the abstract nature of our minds and the complexities of the outside world.

The study of primitive and child art can teach us a lot about the way the mind twists the evidence. The advanced study of drawing used to recommend a number of ways in which we could learn to correct some of the loss that inevitably results from abstraction. Now alas, we have the situation where abstract art is matched with nothing. It is beyond criticism, in a world of its own. Our response to the outside world is visibly deteriorating as a result; particularly in the field of response to our fellow humans. Body-language is often misread which was once reliable and instinctive. This developing loss of touch with reality could endanger our survival as a species. (The catastrophe of Rembrandt scholarship over the last 50 years in de-attributing half his genuine works is a forceful reminder of our loss.)

This brings me to the point where I must attempt an answer to my initial question. The change in the course of art coincides with the rise of art history as a deciding power in art. Previously an artist’s fame was influenced by their standing with their peers, now it is decided by the mass-media directed by art experts who paradoxically know little of what has driven artists in the past. A paradoxical result of introducing professional art historians into British art schools is that a noble history of Man’s endeavor over 40,000 years has been cut down to the last 50. So recent students no longer feel that brotherhood of artists: that conversation with the past that frequently leads to genuine originality.

This essay was triggered by chancing upon a book on drawing “ Studien zur Gestalt des Menschen” (Urania 2005) by Gotfried Bammes. He reproduces splendid drawings by his students on various courses in the German speaking world. Such a book would be near impossible in the English speaking world, we are far too individualistic, aiming at novelty rather than that long established quality that we find here. Congratulations Herr Bammes for keeping civilization alive in difficult times!

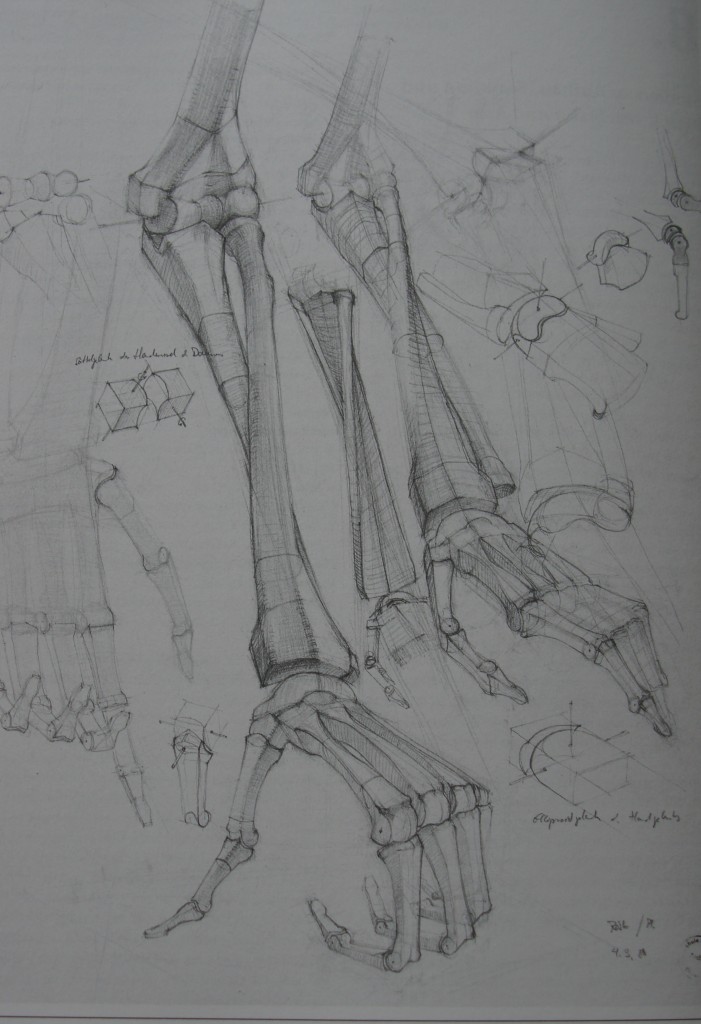

An anatomy drawing by a nameless second year student at art school

Many illustrious artists have wrestled with such subjects in the past. For sensitivity to the quality of bone, to the articulation of the joints and the movement in space I do not think this has ever been bettered. Talent still exists but not the ability to promote it; because we have left that in the hands of a band of deluded experts. We, who do not profit from their delusion recognize it to be a ludicrous scam from which we can only lose (through our pension funds as well as the emptiness of our museums of modern art.) The vast sums spent on encouraging establishment art discourages the eclipsed majority of artists.

Value in art is now dictated by the auctioneers and their gambling clients, who are probably unaware of the damage they are inflicting on civilization.

Copy of Reddit Article

The brain of Man has undergone a transformation since we painted the caves. “In the beginning was the word” the invention of speech was the beginning of that transformation. Speech, number, geometry and mechanics are the chief abstract categories that rule and blinker our perception of the world. They are so useful that they have all but obliterated the rich variety of messages that our animal senses bring us.

It was the chief task of the visual arts to re-examine and extend the interface between the abstract quality of our mindset and the rich variety of the world out there. Traditional artists working from nature and humans soon become aware of how inadequate are our mental images. We know we are burdened with a brain that wants to reduce the world to abstractions. The process of observation brings our abstracting mindset to confront the actual. Each search for understanding

developed by an artist becomes in itself “form”.

The word ‘form’ is generally used to mean three dimensional shape. In art it has another set of meanings. It is also used to mean that which is formalized, or form in the sense of “sonnet form”: a mould into which any number of ideas or feelings can be poured. It can mean manners in the sense of “good form”; manner in the sense of the “Classical manner” which is derived from classical Greek sculpture. It has a structural meaning in the coordination of parts to make a meaningful whole. “Form” can be used to describe a number of conceptual schemes, it is not just meat.

In fact the recognition of form was the chief aim of an education in art. Form is an amalgam of all these ideas and has come to mean that emphasis that comes about from an artist’s interpretation of nature: the aspects the artist particularly wants us to see as important.

Traditional art attempts “to hold a mirror up to nature”. Since the invention of photography this activity has become less rewarding because the camera does this so well. But there is another aspect to the best traditional art which we could describe as the mental digestion of nature; art can be the interface between our habitually abstracting mind and the richness of nature. Art stretches the mind to comprehend more. Around 1904 Art became more conscious of form but recently unconscious.

An art rooted in tradition has the huge advantage of being able to strikes chords in the mind and evoke emotion because of it’s relation to a depth of human experience, recorded and evolving through history. It is our cultural inheritance. The evolution of art is an important part of our appreciation of the visible. As we moved away from the hunter-gatherer, where awareness was all important, we have come to rely on art to keep our senses alive. Without observed art we lose touch with the wealth of what is out there in the world; we receive it less fully, we become less human.

Music and poetry have forms also. In a recent review, a poet was praised for her “impressive formal range… an England rooted in Nature of Chaucer, Shakespeare,Wordsworth and John Clare.” Though I have no ear for poetry I understand what this means because it is similar to visual form, and refers to that cultural inheritance as above.

For instance, in my own experience my love of Rembrandt’s drawings was considerably deepened by visiting a show of Giacometti’s drawings. Giacometti had consciously or unconsciously used space clues similar to Rembrandt’s, his primary focus is on space. Rembrandt, like most draughtsmen, mainly focuses on the solid figures but it is the space between the figures that makes them so meaningful. In my view it is crucial to understand this aspect of Rembrandt’s form. The scholars’ study of style (the mere marks he made) has led the “experts” very far from the Rembrandt recorded by his contemporaries; he has been much diminished by recent scholarship and his philosophy: the primary importance of original observation, has been turned upside down.

************************

Two main lines of development in the form of western art can be seen. That derived from the Greek sculpture is easily recognised in the lay figure which was present in every academic studio. It is epitomized by the work of Raphael but was generally used during the Italian Renaissance and in academic art since.

The Roman is derived from the survey techniques that Roman sculptors used for transferring their work into the permanent medium of stone. It is based on solid geometry as a pattern to compare with nature. The Roman needs to be distinguished from the Greek because it operates with a different syntax. The Roman is more analytical and therefore better adapted to sharpening observation. Each artist gives the tradition a nudge in the direction of their own personal philosophy. Rembrandt used Roman form when he observed; and Greek on those rare occasions when he had to invent: his flying angels for example.

I have made a short film to explain the high points in the development of form with appropriate images (URL). I regard Rembrandt as the greatest humanist draftsman because he realized that the space between two people expresses as much or more than their individual gestures or facial expressions. He developed the Roman form to incorporate space as well as solid.

My rediscovery that Rembrandt deployed groups of live models so as to find the maximum expression and then drew observing the space with the same attention as the solid bodies is contrary to the modern belief among art historians. They refuse to abandon their mistaken belief that imagination is superior to observation in art. Imagination as commonly understood means drawing out of ones head, often no more than construction by formula. Rembrandt understood that the intimate, meaningful space between two figures cannot be constructed, it is too subtle. It has to be observed. This is the secret of his psychological and dramatic gift.

The teaching of form goes through periods of development and decay. Sadly ours is a period of such decay that many young artists have missed ‘form’ in this special sense in their artistic education. They are deprived of that sense of brotherhood with former artists that sustains and supports a living tradition. As a consequence we are losing contact with nature and with the great tradition of seeing as exemplified by recent Rembrandt scholarship. Art matters!

Note. The word form was crucial to artistic discussion before Wolfflin moved the goal posts with his book “The Principles of Art Hisrtory”(1915). He had no conception of the artistic use of the word form.

I am so pleased to have found this website, so full of mavericks like myself. I am a sculptor, nearly 80 years old. I would like to tell you my experience. I may be one of the last generation to receive a training in the observation of form: that illusive abstraction that can help us to understand what is going on out there in the world.

To see form was the whole point of our education and had been for the previous three millennia. Novelty as such, was not part of our ambition; we hoped to give the world new vision, or at least a new emphasis, by adjusting the tradition in some significant way. I looked to Brancusi and Giacometti as examples in this. Through Giacometti I came to see Rembrandt more clearly. This concept of working within a tradition seems to have been lost.

I was a part of the majority of my fellow students in regarding Rembrandt as the one great master who spoke to us directly: the master of form that expressed the movement of the human spirit in the physical world more clearly than any other. He was also number one on the charts of market-value. How radically things have changed since then. (He no longer appears among the top 30 in the charts.)

Art History was taught by the same bright artists who taught in the studios. We saw art as the interface between nature (the model who stood there all day) and the inadequate abstract quality of our own minds grappling to understand nature. The study of art history seemed to confirm that the high points of civilization were those that came to a new understanding of the visible world. We saw the progress towards that understanding as slow and intermittent. There were long periods of decay interrupted by short bursts of brilliant artistic activity such as the Italian Renaissance. The best periods seemed to go hand in hand with a break-through in scientific thought.

The perspective I gained from my education at Camberwell Art School has lasted a life time. I see myself as adding my own small morsel to the sum total of human understanding of the world. My enthusiasm has not waned but my perspective has divided me from the main-stream of art today.

It seems to me that the ‘art promotion machine’ has multiplied in size and power, due to the recent technological advance of colour television and printing, to a point where the artists themselves are no longer in charge. The machine has taken over! Tom Wolfe complained of the same critic-led art in “The Painted Word”. We have recently seen how over €21 million was paid for a painting whose informal design would hardly have raised an admiring eyebrow if seen on a rug 30 years ago. Art is about values, what will future generations think of ours? Our visual culture has sunk to a level unimaginable, since “The Painted Word”. We need a revolution in the way art is run and art history is taught. Art historians desperately need 80% input from artists.

The art promotion machine is largely manned by those trained in art history, they are aided and abetted by dealers, ad-men and critics. The machine makes a great deal of money, in which only a tiny fraction of working artists take a small share. Over the last decade “The Jackdaw” magazine has been exposing truly amazing abuses in the way public art money is handed out in the UK.

The machine has sold us the idea of the avant-guard. We are invited to view it as the evolutionary “cutting edge” in art. But evolution normally relies on chaotic variety which is then selected by the forces of nature for survival or not. The variety exists in art today but the machine has taken upon itself the selection process and jealously guards the power that it gives. Artists or the public do not get a look in. Most will look at the art that has been promoted over the last 50 years with little enthusiasm. There exists an alternative to establishment art but you will not find it in the media or museums of modern art. The machine will not allow the competition that real evolution requires. The machine rules!

With the help of Sir Ernst Gombrich I published my discovery of Rembrandt’s use of mirrors (Burlington Magazine Feb.1977). If heeded that discovery would simplify Rembrandt studies by demolishing most of the Rembrandt scholarship of the last 100 years. It would make a huge difference to his standing today. Modern scholars believe in only 500 drawings by Rembrandt, Otto Benesch’s Catalogue of 1957 published nearly 1400, I believe there are over 2,000 drawings by Rembrandt extant. This is backed by evidence that would be accepted in scientific circles but it is neglected or refuted by art scholarship. You will find my many criticisms on the internet. Please comment if you visit.

Further examples of the errors of art history are outlined below. For a fuller education come to my Research Centre for the True History of Art at Casole d’Elsa, near Siena, Italy. Courses are offered at The Verrocchio Arts Centre.

The following videos by Nigel Konstam came be found at

http://www.nigelkonstam.com/cms/index.php/youtube-videos-by-nigel-konstam

1. Nigel speaks to the BBC about his Rembrandt discovery in 1976

2. The two versions of “The Adoration of the Shepherds”, are both by Rembrandt

3. An obvious fake praised by Rembrandt scholars

4. Many brilliant Rembrandt drawings falsely attributed to Ferdinand Bol

5. A Canonical Rembrandt drawing of his mistress recently de-attributed

6. Verrocchio’s sense of structure

7. Vermeer’s method with 2 mirror + the camera obscura (3 parts)

8. Brunelleschi’s method of arriving at a scientific perspective

In preparation -

Life Casting and Bronze casting in ancient Greece

The two traditions of form in Europe

STOP PRESS

I have scored a palpable hit recently: I am happy to report that the authorities at The National Gallery (London) have returned their painting of “The Adoration of the Shepherds” to it’s rightful place among the Rembrandts. If you visit the two sites on YouTube dealing with that painting you will find a lady from the National Gallery explaining why their picture is not a Rembrandt and myself (Nigel Konstam) explaining why it must be a Rembrandt.

As a student I loved the process of carving but never seemed to like the resulting sculpture. After I left Art Schools I hardly touched carving, just a few wood carvings that simply confirmed that I was not a natural carver. Twenty eight years later there were no carvings in my retrospective exhibitions in Spain. At Camberwell Art School we were taught by a student of Eric Gill’s. We were taught to move round the piece nibbling off bits as we felt fit, reversing the process of modeling. This method does not work because you do not establish the scale of the piece from the beginning. It starts too big and as it dwindles the movement is lost and it becomes sadly disproportioned.

Michelangelo established the scale with the first limb he came across working from one side of the block only. He continued pushing into the block mainly from one or two sides. Not from all round. In this way he always had a reserve of stone to retreat into. We were told how Michelangelo did it; but were warned that he was a genius, where we were not. In fact, what we call the Michelangelo method was followed by most carvers in medieval times. It is just that Michelangelo left so many unfinished works behind that his procedure was obvious.

When I moved to Italy I did not immediately get into carving although the stone here is beautiful and inexpensive. A student wanted to try carving so I got her a piece of alabaster. It was obvious that she was not going to finish in the two week course so I began to help her. It felt good. I got a piece for myself as well. I dared try the Michelangelo method and found it worked! I was hooked. I had not even finished the first piece before it was bought by a passing German couple. That was very reassuring. Though this speed of purchase has never repeated itself to this day. Nowadays I guess I spend more time carving than modeling. Its a slow process.

Carving came to me as a new lease of life in my mid-50s. I do direct carving. That is the initial inspiration comes from the shape of the stone in front of me. The stone rarely speaks to me immediately. I have to work on it for an hour or so tidying up the crude quarried shape. Then I get a vague idea of what I am going to do. It is only a vague idea. Pay no attention to the historians’ optimistic theories that genius sees the whole thing from the very beginning. If they did there would be no fun in carving. The fun comes in giving concrete form to the vague idea. Paying strict attention to the forms which evolve as you work keeps one interested, indeed deeply engaged. There are moments when carving is just hard work but long periods when one is creating, not just copying a prepared model or a figment of the imagination. My imagination works on the concrete object that is taking shape as I work. It is as if I am watching the two protagonists very slowly embrace.

Each move I make helps or hinders the expression. You have to watch every move to see whether it is for better or worse. Carvers move forward by experiment, if the experiment is not working stop and modify it. Its compulsive stuff, hours of absorption pass rapidly. Its a way of life.

One of the great advantages of carving when teaching is that when one is interrupted one can lay down one’s tools and take a break. On taking up the tools again one immediately finds something to do. With modeling an interruption truly interrupts. As a good half of my students are usually carving alongside me, I give little demos as I go along.

As a modeler I work from drawings made from life. As a carver I am forced back onto memory and imagination because the process itself is so slow. It is important to realize that my imagination is fed by the physical shapes in the stone I am working on. I cut clear plains to get clear feed-back. I may have to re-cut the same plain 20 times in the process of finding the optimum expression. What’s the hurry?

My advice to students is not to worry too much about cutting away something vital. In every stone there are millions of possibilities, you are bound to strike one of them! Start on a stone by clarifying a movement that appeals to you. Then one thing usually leads to another, you will find your way. Cut clear shapes and you will get clear feed-back. It is wise not to define forms by cutting top and bottom which will pin you down to a form too thoroughly. Suggest forms by cutting the top and front. A fan shape of stone for a forearm allows and suggests change.

If you can see one step ahead take it and you will see the next step. It is only necessary to see one step at a time. Pay no attention to the historians’ theory that genius sees the complete composition before starting, look at Michelangelo’s unfinished Slaves you will see that it is not true. Like the rest of us he found his way by trial and error.

A book I would strongly recommend as a follow up is “Michelangelo Models, formerly in the Paul von Praun Collection” by Paul James LeBrooy (Creelman and Drummond, Vancouver 1972). There you will see what terrible losses have occurred as a result of the above theory. You will also get a good insight into how Michelangelo actually transmitted his anatomical knowledge to his carvings: first modeling from life, in clay; rather small, so that he could tie the fired terracotta up where he could refer to it as he carved. All so obvious and straight forward but the mythology has overwhelmed the truth.

An edited excerpt from something I wrote in 1971 (Leonardo vol.4)

I have clung to the figure because I find in it a model of great complexity with a wide variety of jointing, scale and mass, and one with which we are all familiar. We not only know what it looks like from the outside: we know what it feels like from the inside. The slightest deviation form the expected norm is noted and questioned. Every human eye is attuned to the figure more precisely than even the educated eye is attuned to mathematical proportions. When one adds to this the geometric, architectural and rhythmic associations that have accumulated around the figure during its long evolution, it become clear that there is a widely available basis for understanding the purely formal meaning of figurative sculpture, which I find lacking in non figurative work. Figurative art is capable of dealing with human emotions in a simple and direct way.

One of the tragic side affects of non figurative art, in my view, has fallen upon art education. We are producing art students who have little or no interest in the art of the past, thus destroying the communion of artists: that sense of partaking in a timeless communion certainly gives me a sense of well being. Indeed, it seem to me to be the only certain reward for the serious study of art. Moreover, I am convinced that the sense of belonging to a privileged circle with access to inner meanings is an important ingredient of the aesthetic experience. If my view is right, estrangement form the past is surely too greater price to pay for the understandable dissatisfaction with the old academies of art.

Communication in art, as in everything else, must be based on a collection of symbols that are commonly understood. I realise that new forms sometimes have to be invented to express genuinely new experiences. However, the huge transformations in art that have taken place in the last fifty years have all but disintegrated the slowly evolving complex of commonly understood visual symbols. More important, does not the effort of making language describe our experiences force us to re-examine and refine the experiences ourselves? Surely only when the present language proves inadequate for our expression can we allow ourselves the indulgence of linguistic invention. To me a newly invented ‘form’ is simply a novelty. Originality must contain a new insight which may or may not need a new ‘form’ for its expression.

We have just had our Palio and I am rather pleased with my photo. I would have been even more dramatic had I waited another second. Rivelino led all the way and we were second, to the relief of many. The drumming and partying can become very wearing. It was lovely weather and still is.

The reform of art history is one of the most pressing needs of our civilization. The desperate errors of judgment that are being perpetrated by our art experts on a daily basis in both modern and ancient art must indicate that something is amiss. I have made more discoveries in the field of art history than anyone alive or dead, yet very few are interested in learning to see what I see. Rembrandt, the greatest humanist artist that has ever lived, is in serious danger of being eliminated from our cultural history.

Surely an artist has equal or better claims on the subject of seeing than an art historian. Observation is after all my daily practice as a sculptor. Whereas, to tell the truth, art historians seem much more interested in each others books than in the objects they claim to be studying. I have the huge advantage over the professionals that I come to those objects without the inbuilt prejudices with which art history blinkers its students. I have considerable practical knowledge in the case of sculpture, casting and drawing. In the case of painting at least I understand what an artist can produce from his unaided memory. The theories of art history are a sick joke in that respect.

During my lecture at Harvard I was told that “in the 17th century artists did not even need still-lives in front of them.” When I asked how they got that idea, the answer came back – certain flower paintings have flowers in them that do not bloom at the same season! I pointed out that flowers wilt, that flower painters pick their specimens one at a time – this caused consternation to all concerned.

This kind of nonsense was meant to justify the idea that Rembrandt did no need models to draw from. An idea that I could see was completely untrue in a ten minute flick through of his drawings. Equal research in the documents of those who actually knew Rembrandt confirmed my certainty that he set up groups of actors to draw from.

As a culture we have tolerated the steady destruction of the Rembrandt in the full glare of publicity, with few a murmurs of complaint. Wake up, you are living in a time of unprecedented descent into visual barbarism. If you are happy with myths stick with art history as it is; otherwise learn to see –

THE REFORM OF ART HISTORY is a 2 week course that will be run on demand from a quorum of 5. Lectures and discussion will be interspersed with practical drawing and sculpture.

Apply to nkonstam@ verrocchio.co.uk

The museum consists of maquettes and instruments with which Nigel Konstam made a number of important discoveries in the field of art history and archaeology. There are also a number of DVDs and documents which explain the reasoning that made him determined to suggest reforms in those faculties. Artists should again take the lead in cultural decision making.

The subjects covered in the museum are in chronological order :- a

GREECE

1. The discovery that the Greeks used life-casting for their life-size figures from the time of Phidias onwards.

2. a chimney on the Acropolis in Athens, and another in Olympia.

3. a method of steaming moulds to recover 70% of the wax usually lost, used at Rhodes and almost certainly elsewhere.

ROME

Roman geometry had an enormous influence on subsequent art that is seldom acknowledged. The analysis of a portrait bust of Hadrian in the British Museum, demonstrates this geometry. Artists who have used it since, like Mantagna, Holbein, Rembrandt and Giacometti, are also represented in the museum.

SIENA

1an appreciation of the works of Rinaldo da Siena recently discovered under the cathedral.

2reasons why the so called Duccio Window cannot be by Duccio.

3 The discovery of the dimension of time in Simone Martini’s Madonna of the Annunciation.

4Lorenzo Maitani’s great work is on the facade of Orvieto Duomo 112sq m. of relief sculpture of very high quality. We have a film showing how he was able to accurately transmit his art to his assistants.

FLORENCE

1The probable use of a polished silver mirror in Brunelleschi’s essay in perspective.

2. The probable use of sculptural maquettes in conjunction with mirrors by Masaccio.

3.Michelangelo’s use of maquettes for preparatory drawings

4. Cellini’s casting method is demonstrated to be very close to the method of Phidias.

REMBRANDT’S use of live models and mirrors, indicating that his contemporaries knew a Rembrandt that modern scholarship has all but destroyed; an artist whose example is very important to artists who observe life today.

VELASQUEZ’ use of a large mirror from the Hall of Mirrors at the Royal Palace in Toledo for the composition and rapid completion of his most important masterpiece – Las Meninas

VERMEER’S use of two mirrors in conjunction with a camera-obscura as an aid for painting.