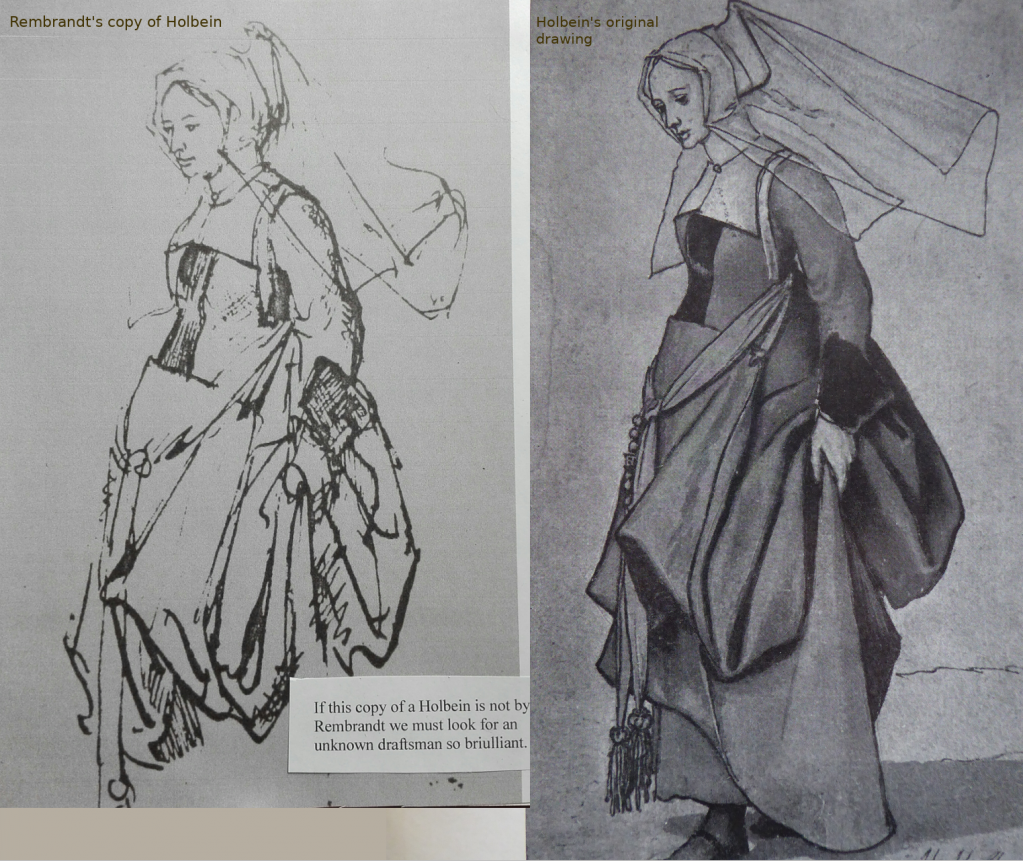

Rembrandt's copy on the left made from Holbein's original on the right

Rembrandt was rather careless in copying his own work (see my comments on his etching of a youth leaning back against a curtain. The preparatory drawing is beautiful but the etching is a travesty of it. The experts have deattributed the drawing!). But in this copy which absolutely must be by Rembrandt, he has actually improved on the original. Holbein was a master of drawing heads using Roman geometry but his figures are less convincing; here Rembrandt could be seen as giving a lesson to his chosen master of a previous generation, more likely the lesson is for himself. Sadly this very important drawing is not in any book of Rembrandt’s drawings that I know; I found it in a collection of reproductions either in The Hague or Amsterdam so long ago I cannot remember the location. I would love to have a better reproduction. This is a very poor photocopy. I would also like knowledge of its whereabouts. As far as I am concerned it is the best proof of Rembrandt’s interest in Roman geometry until his two scrapbooks of studies mentioned above come to light. It is therefore a very important drawing.

The Holbein is one of his best figure studies but it has nothing of the quality of his best heads such as Sir Thomas Cromwell or Jane Seymour which are so abstract that they convey the three dimensional presence with the clear logic of a geometric diagram. Here the figure is still sharply conveyed but lacks that certainty that a sculptor could rely upon.

I will attempt to convey why it is that the Rembrandt copy succeeds better; it is not particularly accurate, The head is broader than Holbein’s. The veils behind are at the wrong angle etc. What impresses me is the articulation of the polyhedra that compose the figure much more solidly than in the Holbein. Compare the shoulders and the top of her chest – Rembrandt uses the strap over her shoulder to define the shoulder and where it meets the side of her chest, where Holbein defines only the garments. It is a subtle difference but crucial to the impression we receive. Reading the whole figure that is exposed down to the lower stomach, Rembrandt’s is a real believable woman where Holbein’s is a cleverly articulated puppet from which stimulus Rembrandt could be said to have imagined, using his memories, a real woman. I guess that the same level of imagination intervened between the mundane presence of his biblical models and the drama he often presents us with; using the mundane, but necessary for him, stimulus (see Homer above for what he produces without that stimulus).

It might be difficult for the layman to believe that a master of the stature of Rembrandt could not produce such works without the mundane stimulus but this lack is frequent at all levels among artists. I have shown it in the masters Uccello, Michelangelo, Holbein and Rembrandt but it is also found among ordinary artists today. The limits of the visual imagination have been misunderstood for centuries. The success of the formula – lay-figure plus anatomy has been sufficient to deceive us but it did not deceive Rembrandt. He made fun of the concept constantly (see his flying angels). Neither we nor the experts have caught on yet.

We have seen the huge gap in ability between Rembrandt the observer and the imaginer. Yet we all conjure images in dreams capable of stirring intense emotions, what is going on? There are several factors that intervene. A story I have often told of an Englishman trying to convince Rodin of the brilliance of Blake’s imagination described them as “real visions” – Rodin replied – he should have looked not once but many times. But of course visions like dreams cannot be conjured at will. In drawing a figure from life one might refer to the model 1000 times or more; this repetition is denied to the visionary. A draughtsman is trying to represent the three dimensional world on a two dimensional surface. This requires a number of perspectival tricks, like the changes in scale as forms recede into the distance and the rules of perspective. These are problems that a sculptor does not have to deal with that is why Michelangelo and others chose to make maquettes to draw from. The gap between Rembrandt as imaginer and his exceptional powers of observing is not in the least unusual among artists.

But he certainly was unusual in his behaviour to the point where I, who have no expertise in psychology, suspect he was quite well along the spectrum of the syndrome of manic depression and perhaps other syndromes as well. From early on he was able to persuade his family who had set their hearts on sending him to a legal profession, instead to send him to an apprenticeship with a local painter. From there they sent him to a well known painter in Amsterdam to continue his studies; he left in six months and set up shop with a younger but more mature student, Jan Lievens from whom he learnt a lot and indeed surpassed him within three years. All commentators agree that Rembrandt was exceptionally talented and hard working; though for me his early work did not show much promise. He was soon promoted by the secretary to the ruler of Holland from whom he was commissioned to paint six paintings of the passion of Christ. You might expect him to set to and produce them, in fact it took him six years to finally deliver the last – still wet! He was paid half his asking price. All the letters we have from Rembrandt were in fact excuses for non-delivery till then. This failure to bow properly to authority was a permanent feature of his behaviour. Two or three commentators said he had no understanding of the importance of social class and kept low company.

As an artist he kept his own council to the end. In poverty and therefore without the band of students to pay for the model groups he resorted to self-portraiture as a subject he could continue to observe. “He was positively generous but nonetheless stooped to pick up low value coins that his students continually painted on the floor as a prank. “He was a first class practical joker who laughed at everyone” He was obviously a very popular teacher and a good one who commanded twice the going rate and in his heyday had many students. He did not treat them as assistants but instructed them conscientiously (see his two examples for Bol) who though a dud turned into a very passable and successful portrait painter under his instruction.

As an artist he was the least reliable master, shifting from exquisite to slapdash in both paining and drawing. It is difficult to make sense of him without taking into account his firmly held belief in “learning from nature and in no other law”.

His business behaviour was well within the etiquette of his day. He was extravagantly generous to his fellow artists, lending them his collection when needed and paying over the odds for their work at auction “so there was never a second bidder”. Done to raise the standing of his profession. At the height of his fame he painted “The Night Watch” without assistance. His fall from economic viability was part of a general economic collapse; as much bad luck as bad management (read “Rembrandt’s House” by Anthony Bailey, a journalist who writes often for The New Yorker rather than a Rembrandt specialist).

As a lover of the three women in his life he behaved well to two and badly to the third by all accounts.. He was a workaholic, working slowly but producing vastly, particularly taking into account his strong teaching commitment.

The experts have misinterpreted all this recently in an effort to bring Rembrandt down to their own understanding – he was a very big character but not difficult to understand seen from the right point of view, the artist’s perspective. They are word-smiths in origin, few of whom have any sympathy with those who learn on the job rather than from books. I am a dyslexic sculptor, one who will consult a cookbook or an instruction manual only as the last resort. I claim this gives me a natural affinity with Rembrandt. At school I showed little mathematical ability but nonetheless came top of the top when it came to solid geometry, this was because I could read with ease those diagrams which flummoxed the real mathematicians. I was naturally drawn to Rembrandt as my artistic ideas took shape. That was at least 10 years before I made my discoveries about him in the Dover paper-backs I bought to prepare for a lecture on Rembrandt that I had been asked to give. I read for the first time experts comments on the drawings and was horrified. That was the beginning of my career in Rembrandt studies. Career may be the wrong word as I have been kept not at arms length but bargepole length by the experts. Never invited to their symposia and on the one time I paid to attend one at the National Gallery (London) which had been advertised as wanting to include the public in the Rembrandt debate, I was refused permission to speak or show three slides by Christopher Brown, the gallery’s expert, with such determination the audience must have assumed I was a mad man.

For millennia art history has overestimated the effectiveness of the visual imagination. What we have truly admired most in art is observation of the real world not imagination. Observation is not as easy or boring as art historians suppose. The stories we tell ourselves, our beliefs get in the way of seeing the world as it is. Anyone who has drawn consistently from nature will tell you how difficult it is to record the two dimensional shapes required to tell us about the three dimensional world. It takes a lot of practice and constant vigilance not to be knocked off course by what one thinks one knows. Our perceptions need to be perpetually questioned.

Most good artists can give us enough to persuade us of what they have in mind but it takes the genius of a Rembrandt to see what is going on out there. And this he did by observation not from imagination as the scholars suppose.

We know what Blake wanted to say but if a dancer produced this gesture at the climax of his piece he would be greeted with uncontrollable laughter, such is the gap between ambition and performance from imagination.

I proved this way back in 1974. That proof was endorsed by Prof.E.H.Gombrich in my Burlington article of Feb.1977 but scholarship has chosen to ignore it and the many proofs of the same I have piled on since. The truth is that present Rembrandt scholarship is entirely out of touch with the historical opinion of those who knew Rembrandt or heard of his behaviour from his students. Scholars follow their inherited bias in favour of imagination have turned Rembrandt upside-down: instead of the artist who “would not attempt a single brushstroke without a living model before his eyes”(Houbraken) we now have a Rembrandt who is assumed to have imagined the bulk of his drawings and an artist whose development has been forced into a most inappropriate mould. This has led to a sequence of further absurdities.

Because of the high standing Rembrandt enjoys among artists today these errors shake the foundations of our art. It is natural to trust the experts but we must remember the experts are human and for humans to contradict the elders of their tribe endangers their life. I can vouch for this because though I am not a member of the tribe of art historians (but a sculptor) my life has been severely disrupted by them. Instead of leading the renewal of Rembrandt scholarship from the centre: I live in a paradise in Tuscany in the hope of attracting students to this inevitable but at the moment, unrewarding task of revising Rembrandt. (see nigelkonstam.com or saveRembrandt.org.uk for details)

All my discoveries were made by asking the right questions, like – how did Vermeer see himself in back view; the professionals don’t seem to think it necessary to see what you are painting, so never ask this question.

The one big difference between my interpretation of Rembrandt’s character as an artist and the characterisation of modern scholars is that I see him as an observer and they insist that he was an imaginative inventor. Benesch writing in “Rembrandt Selected Drawings” (1947) suggested that Rembrandt drew his biblical subjects from an “inner vision…as if he seen them in reality”. Whereas Houbraken (167 ) Rembrandt’s contemporary writes exactly the opposite he said Rembrandt “would not attempt a single brush stroke without living model before his eyes” and I have found massive evidence in the drawings themselves that 98% agrees with Houbraken. In fact all Rembrandt’s contemporaries say much same.

Benesch was writing in the 1947 but today’s scholars seem in complete agreement inasmuch as they have stuck with his method of dating by style and savagely prune those drawings that don’t fit in with his ideas; where I have proved over and over again that his ideas were founded on the erroneous assumptions oft repeated in his “Selected Drawings” of Rembrandt’s imagination. I gave ample evidence of this in my article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” (Burlington February 77) and have added to that evidence with many videos on YouTube; nonetheless, the evidence has been neglected by the scholars.

My evidence backs up Rembrandt’s contemporaries who all described the character I have recovered through his works. My version of Rembrandt would expand the catalogue of drawings, perhaps 30% over Benesch’s “Complete Drawings” – Benesch believed in about 1500 of them. While P. Schatborn, once of The Rijksmuseum, more recently claims to believe in only 500 drawings by Rembrandt (in the Getty catalogue “Rembrandt and his Pupils”). I believe in approximately 2200 and am scandalised by Schatborn’s judgments.

Though I have not had the lifetime of experience among the originals that Schatborn has enjoyed, I believe that successive generations of scholars have dismantled what better connoisseurship once upheld. My own research has largely been among reproductions. My advantage is my sense of Rembrandt has not been hampered by scholarly opinion. I studied art and have had a lifetime of practice in sculpture and drawing. Rembrandt has been and remains chief among my household gods. I find it difficult to understand how the opinion of theoreticians should trump irrefutable evidence - indefinitely.

Modern scholarship finds it difficult to believe Rembrandt could have gained anything from his study of Roman portraiture. He owned 30 Roman busts and filled two books with drawings of them, which must be a measure of his interest in Roman portraits. I believe his preference for truth to nature over idealised beauty and his use of three-dimensional geometry as a draftsman is due to his understanding of Roman geometric form; a clear preference over Greek idealisation.

There are a number of other failures of recent scholarship which I will outline. But the last sentence of the paragraph above is the essence of my struggle with Rembrandt scholars since 1974. (I have recently experienced precisely the same disdain of evidence from archaeologists over a series of discoveries in Greek and Roman art; the new evidence is centred on The Elgin Marbles, I agree with Richard Payne Knight that the majority and the best are Roman restorations.)

Other misunderstanding in recent Rembrandt scholarship – G. Schwartz finds Rembrandt lacking in humour. But Baldinucci describes him “as first rate joker who laughed at everybody” I am amused considerably by some of his drawings – Rembrandt laughs at everybody in a final self-portrait.

More seriously, scholars want great masters to evolve consistently; and as Rembrandt rarely signed or dated his drawings they have had a field-day of arranging his drawings in a neat order that is absurdly mistaken (see YouTube of The Dismissal of Hagar, where we see that the changes in Rembrandt’s style are produced not by Rembrandt’s maturing but by his changing stimulus from reality to a mirror image). Rembrandt was once famous for his responsiveness, he is the least consistent artist I know; partly because of the wide variety of his responses and partly because he was responsible as a teacher – he believed that “one should follow only nature, anything else was worthless in his eyes” and he is the only artist I know who was prepared to demonstrate “worthlessness” in his own drawings when he could not follow nature (see YouTube “Isaac Refusing to Bless Esau” or any of his flying angels).

In his paintings one can see that he developed towards a looser style in the 1650s; the same is probably true of his drawings but the present system of dating by style is clearly wildly mistaken. I have shown evidence for a considerable loss in quality in those drawings made from mirror images (YouTube North Holland dress and “The Dismissal of Hagar”). This loss is almost certainly due to the lesser quality of the stimulus from a 17C. mirror. Plate glass was invented after Rembrandt’s death. His larger mirrors must have been made of either polished metal or composite mirrors made of small pieces mounted together, obviously a less precise image than life direct. I have suggested a spectrum of quality – the best - from a stable stimulus: from life in the studio – a lesser quality from less stable life in the street – lesser still from mirror images and finally the least successful, when Rembrandt is obliged to construct or work from memory/imagination. These characteristics can be observed in action throughout Rembrandt’s life.

Contrary to the above idea that Rembrandt drew best from a stable stimulus – there are two feeble drawings from Roman busts which are included in Benesch’s catalogue but presumably excluded by Rembrandt from the two scrapbooks mentioned in his inventory, which sadly have been lost. Nonetheless, I would stick with my spectrum in a general way, writing off those two as examples of Rembrandt’s variability. A few of his drawings are truly great others much less so. Alas many of the greats have been dismissed by modern scholarship.

Fortunately the etchings are often dated on the plates, they are therefore a reliable source for examining Rembrandt’s variability. They speak clearly of the same wide spectrum from infinitely painstaking, for instance in the shell of 1652, to remarkably crude in some of the earlier compositions, or fairly slapdash when drawing a golfer from life. My analysis of The Lion Hunt etchings on YouTube makes a clear demonstration of the above.

We have to conclude from the etchings that Rembrandt was unreliable throughout his life. My own rule is – if there is any part of a work that could only have been drawn by Rembrandt then it is by Rembrandt; regardless of how awful the rest might be. For instance I defended “The Finding of Moses” drawing (YouTube) from Kenneth Clark’s de-attribution although I agree with his criticism; because this is a drawing about precarious balance that could only have been held by the model for limited time; it does not have Rembrandt’s usual sense of form. I think my comparison with the Virgin Mary with basket B could confirm my interpretation with forensic tests showing both are done with the same pen and ink.

Further examples of Rembrandt’s drawings without visual stimulus – a drawing of Philemon and Baucis with Jupiter B - a drawing so feeble it would never have been accepted as by Rembrandt without the little note he added explaining what it represented. He must have been reading his Ovid and thought the subject could make a painting but no models were available so he did his best without them. He did make a very different and successful painting of it afterwards. These examples should make it obvious Rembrandt needed visual stimulus to produce of his best either as a painter or as a draftsman; His student Hoogstratten advises “ take one or two of your fellow students and act out the scene, some of the greatest masters did the same”.

One last example the drawing of Job and his Comforters which experts believe is Rembrandt correcting a student drawing. Such an interpretations suggest that Rembrandt was a brutally destructive teacher because he has ruined what was an excellent drawing. I describe it instead (on YouTube) as Rembrandt correcting Rembrandt, or more accurately Rembrandt trying a new interpretation over his own excellent drawing. The experts are unable to distinguish between the master and his students it would seem, I find no difficulty, Rembrandt was in an entirely different class. The best of his students were merely adequate.

One of the enduring lessons students can learn from Rembrandt is that he was unself-censoring, entirely self-accepting no matter what the outcome. He could not have foreseen the kind of scrutiny he gets in the analysis of his “Descent from the Cross” in The National Gallery’s “Art in the Making, Rembrandt” but there is not a hint of the hubris there that one finds in Michelangelo, for instance.

I have made a case for a new, more generous catalogue of Rembrandt’s drawings based on a new interpretation of his character as an artist. If you agree please signal your approval below and ask for action from the scholars. Rembrandt was once the role model for art students.

To become a Rembrandt scholar you need to pass out top of a prestigious course in art history. They are the crème della crème; but they are gravely mistaken about Rembrandt and resist correction no matter what the evidence for revision. This article is designed to convince you they need to be replaced. They will not renew themselves.

They have in fact stood Rembrandt on his head. Reversing his significance of perhaps the world’s most perceptive observer. They seek to persuade us that he worked largely from imagination. I believe that I have demonstrated this to be a fundamental mistake, yet they will not budge. As a simple example see my “Isaac Refusing to Bless Esau” on YouTube. I expect you will agree with me that Rembrandt was at his best as an observer.

Esau and Isaac

This disagreement as to whether Rembrandt relied on observation or invention is a fundamental error, which invalidates large areas of recent scholarship. An error from which Rembrandt scholarship is suffering and has suffer since 1922 at when this important drawing was dismissed – important because it shows us Rembrandt’s strengths and weaknesses. Because I accept the weakness I can believe in over 2,000 drawings by Rembrandt but the scholars’ refusal leads them to accept only 500! His position as a culture hero has fallen proportionately in my life time.

I find it very easy to win the observation argument, so I well understand why the scholars refuse to debate the point in public. Choosing instead to undermine my examples in their private world of scholarly publications so they can continue with their folly undisturbed. I have described the scholarship of Rembrandt drawings as “an unmitigated disgrace” for the following reasons:-

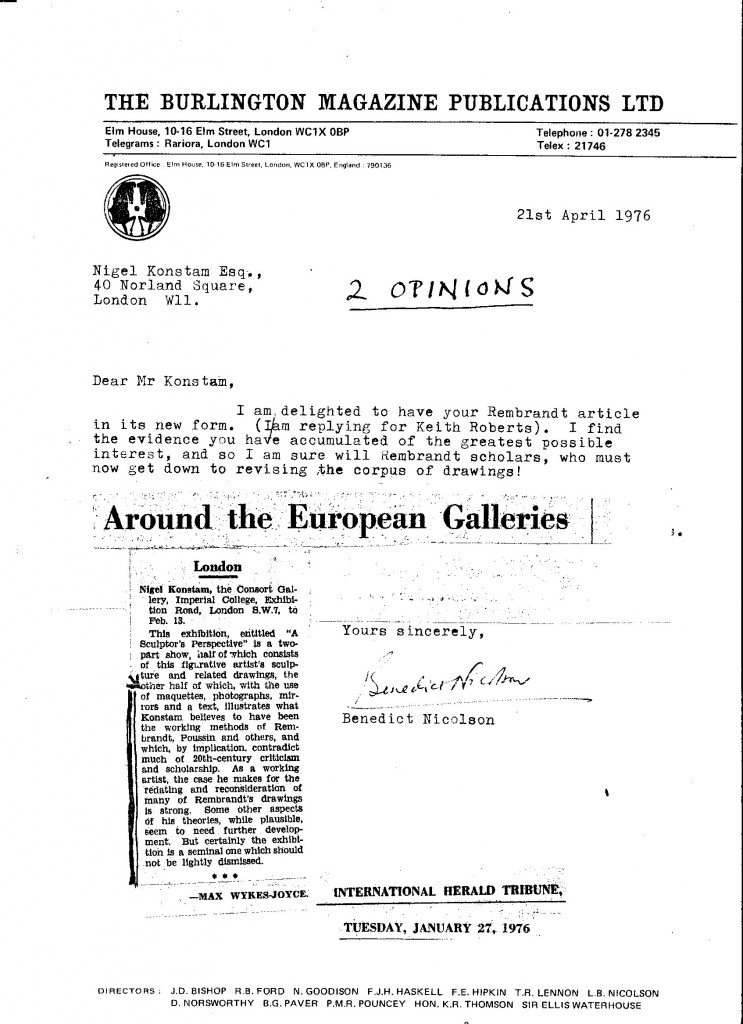

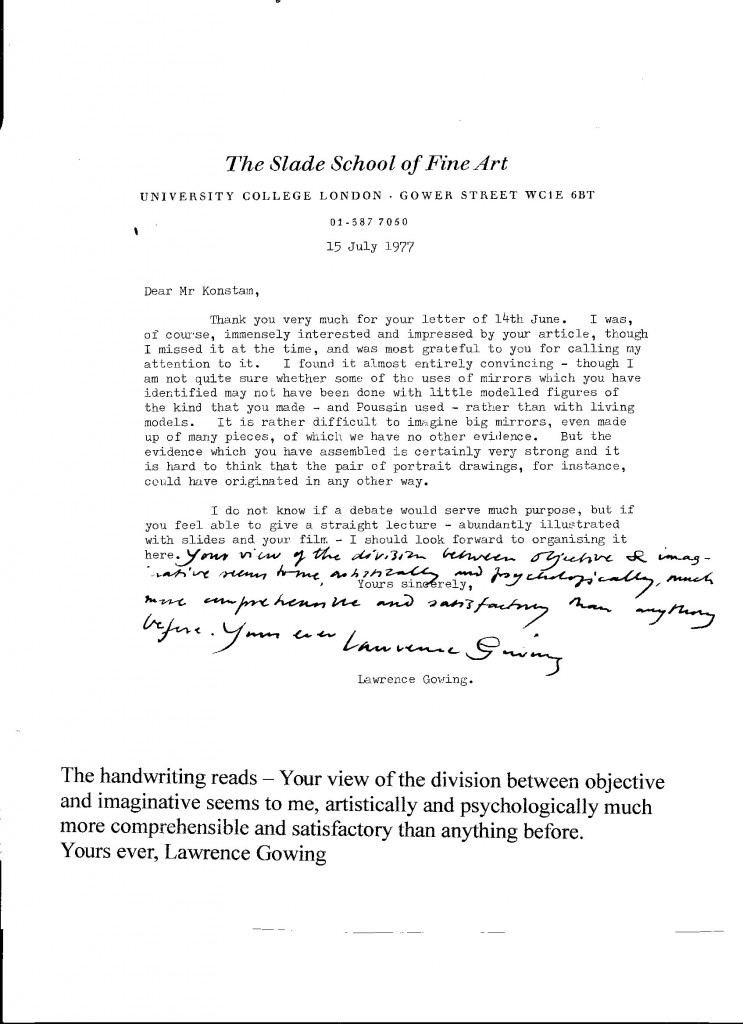

1. My paradigm changing discovery of Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors in 1974 has been neglected. These findings were published in the Burlington under that title in Feb.1977 (two eminent art historians, Prof. Sir Ernst Gombrich and Dr J. Montagu were thanked for their help in presenting my findings in that article). A similar article was published in Rembrandthuiskroniek vol.1 1978. In both I believe I proved, beyond reasonable doubt, that Rembrandt used groups of live models for himself and his students to work from. This idea is anyway corroborated by contemporaries of Rembrandt; what was all that theatrical wardrobe for if not to produce his groups? (an extensive wardrobe and props is seen in the inventory of his belongings taken in 1656.)

2.Recent Rembrandt scholarship has neglected the historical record, indeed reversed the known facts.

3. Over a period of 90 years they have apparently unanimously accepted this reversal, neglecting an abundance of evidence that should have warned them off. They do this in order to maintain their mistaken ideas of Rembrandt’s development as a draughtsman and his relationship with the school production; they have substituted theoretical iconography where practical observation explains the school works better. These sins have suffocated the educational atmosphere of art history. The Rembrandt catastrophe could not have happen without unquestioning acceptance of the professor’s dictate.

4. The scholars refuse to discuss and continue with the destruction of Rembrandt in the face of overwhelming evidence of their folly – or worse.

5. As a sculptor of 60 years experience, I find their judgments often outrageous.

It is the centenary year of the publication of Heindrich Wolfflin’s “The Principles of Art History” often described as epoch-making. It is worth trying to assess to what extent it is responsible for the most devastating decline in artistic standards ever recorded. I would suggest – to a very great extent. I would be interested to know what others feel. Read more

By 1915 revolutions in art were well underway starting with the Impressionists, then more violently with the Post Impressionists and the Fauves. By 1915 Cubism had come and nearly gone. So Wolfflin was not the leader but he was the leader of the critics trying to catch up with revolutionaries.

In his Preface he writes “The Principles arose from the need of establishing on a firmer basis the classifications of art history – not the judgment of value – there is no question of that here”. Nonetheless, his choice of examples and the way he writes about them cannot hide from us the fact that he was no connoisseur himself.

His first example: Durer’s preparatory drawing for Eve, I would probably place as number one among the worst drawings genuinely attributed to an old master. The pose is in itself feeble and expresses nothing of her desire. But it is in the limbs that qualifies his drawing as first in my category. There are no bones in either arm. The one that dangles the apple is particularly disgusting, a mere string of sausages. The leg that bears weight passes muster, no more; from the knee done the other leg looks like the work of a diligent beginner. Yet Wolfflin seems carried away by the beauty of it all. “each single line seems to know that it is beautiful and combines beautifully with its mates.” How could anyone take such a critic seriously? Yet the book is in it’s 6th edition and is ‘a must’ for all students of art history.

Durer’s horrid drawing is compared with one of Rembrandt’ most appealing, individualized, female nudes – Wolfflin writes “Durer is based on tactile, Rembrandt on visual values.” I have made a homage to the Rembrandt in sculpture. I would not dream of such a homage to the Durer, I would be left with a cripple.

Many complain of the loss of connoisseurship while others despise the very idea of it. Surely “The Principles” have delivered the death blow to the whole idea of discerning quality in art. Yet to artists of the past, quality of observation is all that truly matters. Instead of comparing works of art with the phenomena they represent, critics since Wolfflin look at lines as if they have a more important, aesthetic quality in themselves, that they alone can discern.

By 1922 Otto Benesch had embarked upon his devastation of Rembrandt’s drawings, claiming that he could date Rembrandt’s drawings by style “to within a year or two, three at most”! If drawings failed to comply with his pigeon-holes they are discarded. This destructive policy continues under Benesch’s followers at an accelerated rate today. We are left with less than 50% of Rembrandt’s drawings. We have left the fate of Rembrandt, the world’s foremost observer of humankind, in incompetent hands. Are our critics of modern art any better? No wonder the Art World is in turmoil.