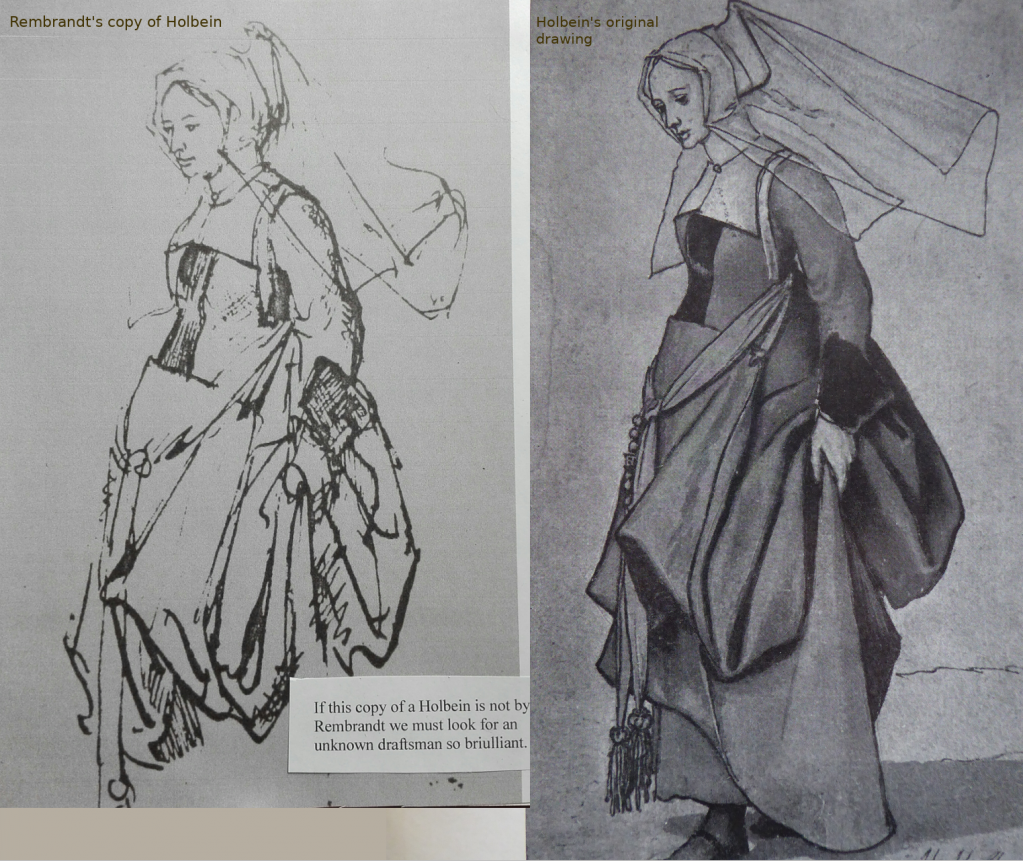

Rembrandt's copy on the left made from Holbein's original on the right

Rembrandt was rather careless in copying his own work (see my comments on his etching of a youth leaning back against a curtain. The preparatory drawing is beautiful but the etching is a travesty of it. The experts have deattributed the drawing!). But in this copy which absolutely must be by Rembrandt, he has actually improved on the original. Holbein was a master of drawing heads using Roman geometry but his figures are less convincing; here Rembrandt could be seen as giving a lesson to his chosen master of a previous generation, more likely the lesson is for himself. Sadly this very important drawing is not in any book of Rembrandt’s drawings that I know; I found it in a collection of reproductions either in The Hague or Amsterdam so long ago I cannot remember the location. I would love to have a better reproduction. This is a very poor photocopy. I would also like knowledge of its whereabouts. As far as I am concerned it is the best proof of Rembrandt’s interest in Roman geometry until his two scrapbooks of studies mentioned above come to light. It is therefore a very important drawing.

The Holbein is one of his best figure studies but it has nothing of the quality of his best heads such as Sir Thomas Cromwell or Jane Seymour which are so abstract that they convey the three dimensional presence with the clear logic of a geometric diagram. Here the figure is still sharply conveyed but lacks that certainty that a sculptor could rely upon.

I will attempt to convey why it is that the Rembrandt copy succeeds better; it is not particularly accurate, The head is broader than Holbein’s. The veils behind are at the wrong angle etc. What impresses me is the articulation of the polyhedra that compose the figure much more solidly than in the Holbein. Compare the shoulders and the top of her chest – Rembrandt uses the strap over her shoulder to define the shoulder and where it meets the side of her chest, where Holbein defines only the garments. It is a subtle difference but crucial to the impression we receive. Reading the whole figure that is exposed down to the lower stomach, Rembrandt’s is a real believable woman where Holbein’s is a cleverly articulated puppet from which stimulus Rembrandt could be said to have imagined, using his memories, a real woman. I guess that the same level of imagination intervened between the mundane presence of his biblical models and the drama he often presents us with; using the mundane, but necessary for him, stimulus (see Homer above for what he produces without that stimulus).

It might be difficult for the layman to believe that a master of the stature of Rembrandt could not produce such works without the mundane stimulus but this lack is frequent at all levels among artists. I have shown it in the masters Uccello, Michelangelo, Holbein and Rembrandt but it is also found among ordinary artists today. The limits of the visual imagination have been misunderstood for centuries. The success of the formula – lay-figure plus anatomy has been sufficient to deceive us but it did not deceive Rembrandt. He made fun of the concept constantly (see his flying angels). Neither we nor the experts have caught on yet.

We have seen the huge gap in ability between Rembrandt the observer and the imaginer. Yet we all conjure images in dreams capable of stirring intense emotions, what is going on? There are several factors that intervene. A story I have often told of an Englishman trying to convince Rodin of the brilliance of Blake’s imagination described them as “real visions” – Rodin replied – he should have looked not once but many times. But of course visions like dreams cannot be conjured at will. In drawing a figure from life one might refer to the model 1000 times or more; this repetition is denied to the visionary. A draughtsman is trying to represent the three dimensional world on a two dimensional surface. This requires a number of perspectival tricks, like the changes in scale as forms recede into the distance and the rules of perspective. These are problems that a sculptor does not have to deal with that is why Michelangelo and others chose to make maquettes to draw from. The gap between Rembrandt as imaginer and his exceptional powers of observing is not in the least unusual among artists.

But he certainly was unusual in his behaviour to the point where I, who have no expertise in psychology, suspect he was quite well along the spectrum of the syndrome of manic depression and perhaps other syndromes as well. From early on he was able to persuade his family who had set their hearts on sending him to a legal profession, instead to send him to an apprenticeship with a local painter. From there they sent him to a well known painter in Amsterdam to continue his studies; he left in six months and set up shop with a younger but more mature student, Jan Lievens from whom he learnt a lot and indeed surpassed him within three years. All commentators agree that Rembrandt was exceptionally talented and hard working; though for me his early work did not show much promise. He was soon promoted by the secretary to the ruler of Holland from whom he was commissioned to paint six paintings of the passion of Christ. You might expect him to set to and produce them, in fact it took him six years to finally deliver the last – still wet! He was paid half his asking price. All the letters we have from Rembrandt were in fact excuses for non-delivery till then. This failure to bow properly to authority was a permanent feature of his behaviour. Two or three commentators said he had no understanding of the importance of social class and kept low company.

As an artist he kept his own council to the end. In poverty and therefore without the band of students to pay for the model groups he resorted to self-portraiture as a subject he could continue to observe. “He was positively generous but nonetheless stooped to pick up low value coins that his students continually painted on the floor as a prank. “He was a first class practical joker who laughed at everyone” He was obviously a very popular teacher and a good one who commanded twice the going rate and in his heyday had many students. He did not treat them as assistants but instructed them conscientiously (see his two examples for Bol) who though a dud turned into a very passable and successful portrait painter under his instruction.

As an artist he was the least reliable master, shifting from exquisite to slapdash in both paining and drawing. It is difficult to make sense of him without taking into account his firmly held belief in “learning from nature and in no other law”.

His business behaviour was well within the etiquette of his day. He was extravagantly generous to his fellow artists, lending them his collection when needed and paying over the odds for their work at auction “so there was never a second bidder”. Done to raise the standing of his profession. At the height of his fame he painted “The Night Watch” without assistance. His fall from economic viability was part of a general economic collapse; as much bad luck as bad management (read “Rembrandt’s House” by Anthony Bailey, a journalist who writes often for The New Yorker rather than a Rembrandt specialist).

As a lover of the three women in his life he behaved well to two and badly to the third by all accounts.. He was a workaholic, working slowly but producing vastly, particularly taking into account his strong teaching commitment.

The experts have misinterpreted all this recently in an effort to bring Rembrandt down to their own understanding – he was a very big character but not difficult to understand seen from the right point of view, the artist’s perspective. They are word-smiths in origin, few of whom have any sympathy with those who learn on the job rather than from books. I am a dyslexic sculptor, one who will consult a cookbook or an instruction manual only as the last resort. I claim this gives me a natural affinity with Rembrandt. At school I showed little mathematical ability but nonetheless came top of the top when it came to solid geometry, this was because I could read with ease those diagrams which flummoxed the real mathematicians. I was naturally drawn to Rembrandt as my artistic ideas took shape. That was at least 10 years before I made my discoveries about him in the Dover paper-backs I bought to prepare for a lecture on Rembrandt that I had been asked to give. I read for the first time experts comments on the drawings and was horrified. That was the beginning of my career in Rembrandt studies. Career may be the wrong word as I have been kept not at arms length but bargepole length by the experts. Never invited to their symposia and on the one time I paid to attend one at the National Gallery (London) which had been advertised as wanting to include the public in the Rembrandt debate, I was refused permission to speak or show three slides by Christopher Brown, the gallery’s expert, with such determination the audience must have assumed I was a mad man.