|

|

As an artist working primarily from life, I am acutely aware that nature provides the observer with a hugely complex amount of visual information so any ‘gadget’ or aid to seeing which simplifies the process is always of interest. Having produced this painting with the use of two mirrors, I can appreciate the practical advantages:

1. The complete image, as seen in the easel mirror, is considerably smaller than ‘real life’ and it is all in focus, making it easier to judge the final effect. As a result, the spacial relationships and colour balances within the painting can be fully considered and explored before brush is ever put to canvas.

2. Using a present-day mirror reduces the light areas in tone making the judgement of relative tones on the palette much easier – a more primitive 17th century mirror would have reduced them still further.

3.The artist can position his easel in the same light that bathes the subject of his painting. This is a decided advantage in a small studio, particularly if the artist wants to depict himself from behind.

My own experience of the camera obscura is that it achieves none of these things and would actually hinder the painting process as the artist needs to see the paints on his palette in the same light that he views the painting. However, an image through a lens could well have influenced Vermeer’s vision, such that he chose to paint objects slightly out of focus, as an extra technique for creating his reality.

Close study of Vermeer’s interiors reveals him as a precise thinker and it seems to me that he worked slowly and thoroughly making few changes as he went along. I also think he was well ahead of his time in the way he created atmosphere with colour composition and the effect of light filling the spacial volumes.

All artist’s have their different methods. I suspect that Vermeer elongated the orthogonals in the foreground to create more spacial volumes in his interiors, as, for example, in “The Music Lesson” painting. The traditional chequered flooring would have been a great help for that.

- The Music Lesson, Vermeer

The historical facts of the time lead me to think that, inevitably, he would have investigated and experimented with any new optical tools but I think it is highly unlikely that he actually used the camera obsura images to paint from.

WEB SITE: www.anneshingleton.com

On the 20th of January I gave a talk to the British Institute of Florence as part of their cultural programme. The subject was “The Museum of Artists’ Secrets” housed here at the Centro d’Arte Verrocchio. The talk was very well received.

A lot of artists were present and asked a lot of good questions; I hope I gave them good answers. Certainly many promised to come and visit the museum for themselves. Seeing is believing! In the time available (one hour) it was only possible to mention in a cursory way most of the exhibits.

I started with my discovery of the use of life-casts in ancient Greece from around 490 BC (Pliny tells us that life-casting was invented around 350 BC by the brother of Lyssipus). This produced some sceptical questions. Unfortunately I had not brought exhibit No.1, the wax foot cast from life, which I regard as the evidence that puts the matter beyond reasonable doubt. Charles Cecil, who runs a very successful school in Florence, promised to investigate the matter further either with a visit here with his students or for me to visit his school.

I then gave a brief summary of the geometry of Roman portraits with photos of the carving process for the bust of Hadrian from the British Museum. And demonstrated how this geometry had become part of the syntax of the Alternative Tradition in European art: the tradition of Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt and Degas. I should perhaps have included Giacometti in the list of examples.

I gave a long build up of the importance of Rembrandt’s drawing B1121 (included in this blog) and finally shocked them with the news that it had been re-attributed to Aert de Gelder. At that point I made a strong bid for their help in making the RRP and the drawing “experts” pay attention to what I was saying. I have never been so clear and forceful on this point before and it really seemed to strike home. ( A young Dutch woman offered her help at the end and I promised her a DVD to help her on her way.) Richard Serrin, a well known painter, said he had been studying Rembrandt for 50 years and what I had said made a lot of sense to him. He paints rather Rembrandtesque subjects.

It was gratifying that so many of the painters of Florence came and were excited by these new interpretations of Rembrandt’s artistic character. I certainly stirred them up. I finished with two excerpts from our DVDs of Maitani and Rembrandt. I had to cut “Duccio’s Window” and Simone Martini as I had gone over time. Wine was served to all afterwards and I was presented with a bottle of Brunello for my pains. We drank it with great pleasure at supper. A good night out.

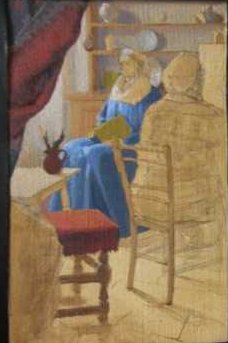

Anne's Vermeer, all but finished.(26 X 16 cm) oil on canvas

After some days of very poor light Anne has very nearly completed the painting. Using the size of the image as seen in the easel mirror the painting is remarkably small. Although the necessary space for a studio using the mirror method is very small the visual distance from the main subject (Rembrandt and side-board) is actually 3.95 m, this is because the light hits the large mirror then the second mirror on the easel and finally comes to her eye. This distance causes the small image.

Anne's Painting

Our big mirror was narrower than Vermeer’s, accounting for our somewhat cramped composition. By using a wider mirror than we have behind, the angle of vision could be widened considerably.

The large areas of fabric or carpet that one finds in the foreground in many of Vermeer’s paintings was there to provide an undemanding area of the painting that would cover over the area where he would have seen himself directly reflected in the easel mirror. In Anne’s case we see her right shoulder blotted out the left-hand corner of the picture which she then painted with green and striped fabric following Vermeer’s example. This is another strong argument in favour of Vermeer’s use of two mirrors rather that the camera obscura. With the camera obscura the artist is hidden behind the lens, so the image of the subject would have been complete.

I feel that Anne’s painting is very Vermeer like; in the simplifications of Rembrandt’s face for instance. Also in the very accurate and simple recording of the patches of light coming from the objects on the shelves behind, which gives precedence to the light rather than the description of the object itself. This is particularly typical and very much the result of the method of observation. Until someone comes up with something more Vermeer-like observed in a camera obscura; I am persuaded that this method, which was strongly hinted at in “The Art of Painting”, was in fact Vermeer’s method.

For me Vermeer is the first painter to be primarily concerned with light. It can be no coincidence that the inventor of the microscope lived in Delft. He was Vermeer’s contemporary, he was the first to see microbes swimming in water. The telescope also was a recent invention and was being improved throughout Vermeer’s life-time, bringing revolutionary knowledge to mankind through the medium of light. Light is the prime way we receive the outside world and Vermeer investigated its properties (focused and unfocused) with single minded “scientific”devotion. It was for this reason that he was obliged to use the camera obscura: to study unfocused light. He could have used it also for the planing stage of his paintings but two mirrors, or the better known methods mentioned above, would also have produced the same perspective effects.

|

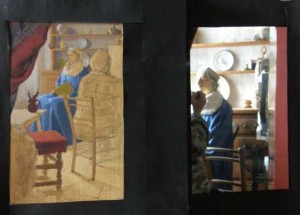

The photo shows a reflection in the easel mirror (above) for comparison with the same in pewter (below). The pewter is a poor substitute for a 17thC silver-backed mirror which we believe Vermeer would have used but we do not possess. The pewter gives a tonal range that is too reduced to be of practical assistance to a painter. Silver turns black over a period of years in light. Experiment could show whether Vermeer's mirrors were new or old, certainly they would have been silvered. |

The palette-knife is held against the reflection in the easel mirror to aid the process of matching the colours and tones. |

Since the publication of “Vermeer’s Camera” by Philip Steadman it has become accepted that Vermeer used a camera obscura. Steadman is an architect by training he is most knowledgeable about the mathematics of drawing. His book is a very thorough review of the literature on Vermeer. He rightly opts for Lawrence Gowing as the leading expert. Many may not know that Gowing was for the first half of his career, a fine tonal painter. From his book it is perfectly clear that Vermeer was his role model.

Gowing is very much more in touch with what a painter gets from Vermeer than Steadman. Gowing writes “the optical basis of his method is most visible not in the planning…….so much as in the tonal recording of certain passages” later he describes Vermeer’s work “as statements of light purged of any other content”. It is this essence of Vermeer that “Vermeer’s Camera” fails to address. The camera obscura would be a positive handicap in achieving these qualities. We can be quite certain that Gowing would have taken one look at the “dark images” the camera provided and turned away disappointed.

Most recent authorities agree that the camers obscura was used, and I am certainly persuaded that it was but my interpretation is different to Steadman’s. The eye automatically refocuses. However determinedly one may try to observe objects out of focus one fails to see anything approaching Vermeer’s out of focus effects, which must be deliberate.

Steadman shows that Vermeer could have been in touch with the most advanced optical experiments of his day. The anatomy of the eye was sufficiently understood to know that it, like the camera, must also go out of focus but only the camera allows one to study light in this condition. This is Vermeer’s prime use of the camera. The planning stage could equally well have been done with Durer’s screen and fixed eye point or Alberti’s net, or Brunelleschi’s constructional method, as Steadman readily admits.

Here we are experimenting with an arrangement of mirrors which is cryptically described in Vermeer’s largest painting “The Art of Painting”. The interpretation was first proposed by Willenski. I arrived separately at the same conclusion through my interest in artists’ use of mirrors and wrote it up in 1980 after conducting the simple experiment which Willenski failed to make. It works. Incidentally this arrangement can also explains the geometry of the results.

Essentially we are pursuing Willenski’s line of thought into the practice. Anne Shingleton, who is a painter trained in the old school (by Simi) and who has 30 years experience of painting light, is in the driving seat.

Here in the library of The Centro d' Arte Verrocchio we see Anne sitting between two mirrors. The big one behind her is somewhat narrower than that used by Vermeer. It is 53x130cm with generous bevels and a frame, which rests on the floor. The plane of the mirror is very nearly parallel to the end wall. The smaller one on her easel, for simplicity is masked off at 26 high x 16cm. wide. The angle between the two mirrors is approx 30 degrees.

Her first reaction on looking at the image in the second mirror on the painting easel was. “Wow, I would like to try it, it seems such a good idea”. She went back to her studio and immediately produced a painting with the method, she said “ the experience has been of great value and has made me look at Vermeer’s work with a completely different eye. The main advantages of working in this way are :-

1. You see the whole composition in the second mirror and so you can move objects around to achieve a pleasing colour and tonal balance before you start.

2. The image in the mirror is conveniently small in comparison with reality, making it easier to judge the balances within the composition.

3. The image can be traced off the mirror, or as it’s viewed sight size can therefore easily be drawn on to a canvas.

4. Above all the tonal range can be analysed much more easily because the intensity of the light is reduced by being reflected off two mirrors and is not thrown out of balance. (Two 17thC mirrors would have reduced the light still further.)

5. The objects are quite far away so the details are more difficult to observe but for a painter this is a definite advantage as the this helps perception of the main light and dark areas.

6. The heavy drape in the immediate foreground also helps the artist judge the more subtle area of light by providing the darkest darks and sometimes the richest colours for comparison within the picture frame.

The artist's task is to mentally compress and adjust this tonal range down a series of tonal notches to that which his paints can span to produce the same scene, maintaining all the time the delicate relationships between all the middle tones. Here we see the painting (left) and the reduced image in the second mirror (right).

Judging the tones of a scene and converting them into paint for a painting is a skill that requires much practice to master. There are many approaches. When we look at a scene with the naked eye we see the lightest areas and the darkest areas and the rest is made up of all the multitude of tones between. (Our eyes also adapt in many ways, for example by changing the width of the pupil, allowing us to work with a really wide tonal range.) Our eyes are wonderful machines to perceive light.

Simply put, the task of the painter is to trick the eye into seeing the same scene, but reproduced using the darkest paint, black, to represent the darkest dark, and the lightest paint, white, to represent the lightest light, and to reconstruct all the tones in-between. Looking at a scene with the naked eye it is quite difficult to imagine, for example that the bright shine on a white, porcelain jug, would have to represent the white pigment on your palette, when the actual white pigment held up on a palette knife in front of the jug actually compares in tone more closely to the lit side of the jug. Thus, the artist’s task is to mentally compress and adjust this tonal range down a series of tonal notches to that which his paints can span to produce the same scene, maintaining all the time the delicate relationships between all the middle tones. The visual reality is reconstructed in painted areas of tone that balance well with each other on the canvas and create the illusion of the same scene. Mirrors which help reduce the light intensity are certainly a useful tool here.

To judge all the light and dark values the artist uses a palette on which to mix up the colours. The colours are arranged around the edge. It is portable because the palette must be seen in the same light that the canvas is lit by. I do not think an artist could look at a very lowlight image in a dark box and then return to mix up the colours in the daylight outside the box. It would be a very impractical way of working, since for each mix you would be comparing many times, and there would be a pause each time as your eyes adjusted to the large change in light intensity. This is another advantage of the two mirrors over the camera obscura.

I have recently studied an image through a camera obscura and did not find it remotely inviting to paint. Steadman’s explanation of the necessary technique with blinds sounds too complicated by comparison with the ease of this mirror method.

The first days work was spent in arranging the composition using Vermeer’s colour schemes as a guide. The back mirror is only 3.10m from the wall. A remarkably small studio space. And this is perhaps the strongest argument against Steadman who requires a palatial studio for Vermeer’s camera. Could Vermeer, who was driven to paying his baker’s bill with a painting and died in debt, possibly have afforded such a studio? Think of the heating bills in Holland in the winter.