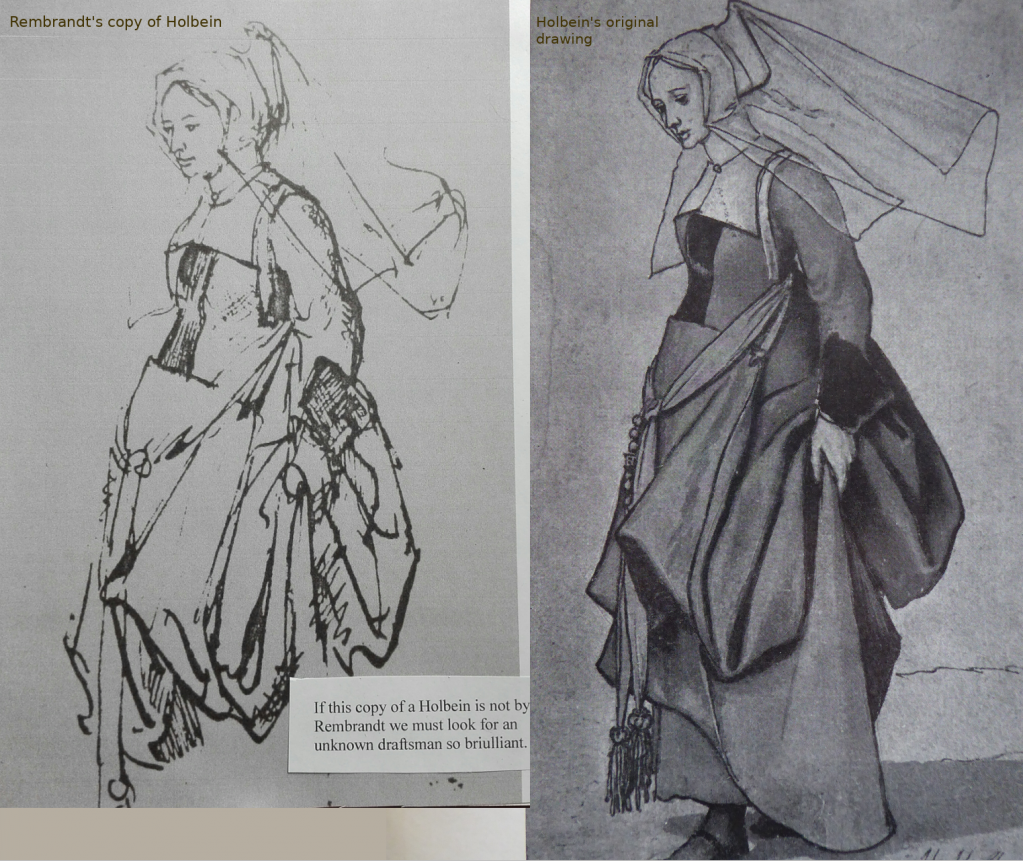

Rembrandt's copy on the left made from Holbein's original on the right

Rembrandt was rather careless in copying his own work (see my comments on his etching of a youth leaning back against a curtain. The preparatory drawing is beautiful but the etching is a travesty of it. The experts have deattributed the drawing!). But in this copy which absolutely must be by Rembrandt, he has actually improved on the original. Holbein was a master of drawing heads using Roman geometry but his figures are less convincing; here Rembrandt could be seen as giving a lesson to his chosen master of a previous generation, more likely the lesson is for himself. Sadly this very important drawing is not in any book of Rembrandt’s drawings that I know; I found it in a collection of reproductions either in The Hague or Amsterdam so long ago I cannot remember the location. I would love to have a better reproduction. This is a very poor photocopy. I would also like knowledge of its whereabouts. As far as I am concerned it is the best proof of Rembrandt’s interest in Roman geometry until his two scrapbooks of studies mentioned above come to light. It is therefore a very important drawing.

The Holbein is one of his best figure studies but it has nothing of the quality of his best heads such as Sir Thomas Cromwell or Jane Seymour which are so abstract that they convey the three dimensional presence with the clear logic of a geometric diagram. Here the figure is still sharply conveyed but lacks that certainty that a sculptor could rely upon.

I will attempt to convey why it is that the Rembrandt copy succeeds better; it is not particularly accurate, The head is broader than Holbein’s. The veils behind are at the wrong angle etc. What impresses me is the articulation of the polyhedra that compose the figure much more solidly than in the Holbein. Compare the shoulders and the top of her chest – Rembrandt uses the strap over her shoulder to define the shoulder and where it meets the side of her chest, where Holbein defines only the garments. It is a subtle difference but crucial to the impression we receive. Reading the whole figure that is exposed down to the lower stomach, Rembrandt’s is a real believable woman where Holbein’s is a cleverly articulated puppet from which stimulus Rembrandt could be said to have imagined, using his memories, a real woman. I guess that the same level of imagination intervened between the mundane presence of his biblical models and the drama he often presents us with; using the mundane, but necessary for him, stimulus (see Homer above for what he produces without that stimulus).

It might be difficult for the layman to believe that a master of the stature of Rembrandt could not produce such works without the mundane stimulus but this lack is frequent at all levels among artists. I have shown it in the masters Uccello, Michelangelo, Holbein and Rembrandt but it is also found among ordinary artists today. The limits of the visual imagination have been misunderstood for centuries. The success of the formula – lay-figure plus anatomy has been sufficient to deceive us but it did not deceive Rembrandt. He made fun of the concept constantly (see his flying angels). Neither we nor the experts have caught on yet.

We have seen the huge gap in ability between Rembrandt the observer and the imaginer. Yet we all conjure images in dreams capable of stirring intense emotions, what is going on? There are several factors that intervene. A story I have often told of an Englishman trying to convince Rodin of the brilliance of Blake’s imagination described them as “real visions” – Rodin replied – he should have looked not once but many times. But of course visions like dreams cannot be conjured at will. In drawing a figure from life one might refer to the model 1000 times or more; this repetition is denied to the visionary. A draughtsman is trying to represent the three dimensional world on a two dimensional surface. This requires a number of perspectival tricks, like the changes in scale as forms recede into the distance and the rules of perspective. These are problems that a sculptor does not have to deal with that is why Michelangelo and others chose to make maquettes to draw from. The gap between Rembrandt as imaginer and his exceptional powers of observing is not in the least unusual among artists.

But he certainly was unusual in his behaviour to the point where I, who have no expertise in psychology, suspect he was quite well along the spectrum of the syndrome of manic depression and perhaps other syndromes as well. From early on he was able to persuade his family who had set their hearts on sending him to a legal profession, instead to send him to an apprenticeship with a local painter. From there they sent him to a well known painter in Amsterdam to continue his studies; he left in six months and set up shop with a younger but more mature student, Jan Lievens from whom he learnt a lot and indeed surpassed him within three years. All commentators agree that Rembrandt was exceptionally talented and hard working; though for me his early work did not show much promise. He was soon promoted by the secretary to the ruler of Holland from whom he was commissioned to paint six paintings of the passion of Christ. You might expect him to set to and produce them, in fact it took him six years to finally deliver the last – still wet! He was paid half his asking price. All the letters we have from Rembrandt were in fact excuses for non-delivery till then. This failure to bow properly to authority was a permanent feature of his behaviour. Two or three commentators said he had no understanding of the importance of social class and kept low company.

As an artist he kept his own council to the end. In poverty and therefore without the band of students to pay for the model groups he resorted to self-portraiture as a subject he could continue to observe. “He was positively generous but nonetheless stooped to pick up low value coins that his students continually painted on the floor as a prank. “He was a first class practical joker who laughed at everyone” He was obviously a very popular teacher and a good one who commanded twice the going rate and in his heyday had many students. He did not treat them as assistants but instructed them conscientiously (see his two examples for Bol) who though a dud turned into a very passable and successful portrait painter under his instruction.

As an artist he was the least reliable master, shifting from exquisite to slapdash in both paining and drawing. It is difficult to make sense of him without taking into account his firmly held belief in “learning from nature and in no other law”.

His business behaviour was well within the etiquette of his day. He was extravagantly generous to his fellow artists, lending them his collection when needed and paying over the odds for their work at auction “so there was never a second bidder”. Done to raise the standing of his profession. At the height of his fame he painted “The Night Watch” without assistance. His fall from economic viability was part of a general economic collapse; as much bad luck as bad management (read “Rembrandt’s House” by Anthony Bailey, a journalist who writes often for The New Yorker rather than a Rembrandt specialist).

As a lover of the three women in his life he behaved well to two and badly to the third by all accounts.. He was a workaholic, working slowly but producing vastly, particularly taking into account his strong teaching commitment.

The experts have misinterpreted all this recently in an effort to bring Rembrandt down to their own understanding – he was a very big character but not difficult to understand seen from the right point of view, the artist’s perspective. They are word-smiths in origin, few of whom have any sympathy with those who learn on the job rather than from books. I am a dyslexic sculptor, one who will consult a cookbook or an instruction manual only as the last resort. I claim this gives me a natural affinity with Rembrandt. At school I showed little mathematical ability but nonetheless came top of the top when it came to solid geometry, this was because I could read with ease those diagrams which flummoxed the real mathematicians. I was naturally drawn to Rembrandt as my artistic ideas took shape. That was at least 10 years before I made my discoveries about him in the Dover paper-backs I bought to prepare for a lecture on Rembrandt that I had been asked to give. I read for the first time experts comments on the drawings and was horrified. That was the beginning of my career in Rembrandt studies. Career may be the wrong word as I have been kept not at arms length but bargepole length by the experts. Never invited to their symposia and on the one time I paid to attend one at the National Gallery (London) which had been advertised as wanting to include the public in the Rembrandt debate, I was refused permission to speak or show three slides by Christopher Brown, the gallery’s expert, with such determination the audience must have assumed I was a mad man.

For millennia art history has overestimated the effectiveness of the visual imagination. What we have truly admired most in art is observation of the real world not imagination. Observation is not as easy or boring as art historians suppose. The stories we tell ourselves, our beliefs get in the way of seeing the world as it is. Anyone who has drawn consistently from nature will tell you how difficult it is to record the two dimensional shapes required to tell us about the three dimensional world. It takes a lot of practice and constant vigilance not to be knocked off course by what one thinks one knows. Our perceptions need to be perpetually questioned.

Most good artists can give us enough to persuade us of what they have in mind but it takes the genius of a Rembrandt to see what is going on out there. And this he did by observation not from imagination as the scholars suppose.

We know what Blake wanted to say but if a dancer produced this gesture at the climax of his piece he would be greeted with uncontrollable laughter, such is the gap between ambition and performance from imagination.

I proved this way back in 1974. That proof was endorsed by Prof.E.H.Gombrich in my Burlington article of Feb.1977 but scholarship has chosen to ignore it and the many proofs of the same I have piled on since. The truth is that present Rembrandt scholarship is entirely out of touch with the historical opinion of those who knew Rembrandt or heard of his behaviour from his students. Scholars follow their inherited bias in favour of imagination have turned Rembrandt upside-down: instead of the artist who “would not attempt a single brushstroke without a living model before his eyes”(Houbraken) we now have a Rembrandt who is assumed to have imagined the bulk of his drawings and an artist whose development has been forced into a most inappropriate mould. This has led to a sequence of further absurdities.

Because of the high standing Rembrandt enjoys among artists today these errors shake the foundations of our art. It is natural to trust the experts but we must remember the experts are human and for humans to contradict the elders of their tribe endangers their life. I can vouch for this because though I am not a member of the tribe of art historians (but a sculptor) my life has been severely disrupted by them. Instead of leading the renewal of Rembrandt scholarship from the centre: I live in a paradise in Tuscany in the hope of attracting students to this inevitable but at the moment, unrewarding task of revising Rembrandt. (see nigelkonstam.com or saveRembrandt.org.uk for details)

All my discoveries were made by asking the right questions, like – how did Vermeer see himself in back view; the professionals don’t seem to think it necessary to see what you are painting, so never ask this question.

Instinct is often spoken about by artists but it is not the same kind of animal instinct that allows birds to fly backwards and forwards across the globe or any other instinctive behaviour of animals. Artists’ instincts are largely composed of memories of art, or of life itself. We all have memories of life, whether we are artists or not, it is this allows communication to take place. An artist’s instinct is cultural rather than genuinely instinctive. It seems instinctive only in the sense that it is learnt through vision not through rational, verbal communication. Much of the judgement made by artists under the banner of ‘instinct’ is built-in cultural preference.

Where this instinct comes in for artists is the use of the 5000 year old language of form, which is mainly inherited and cannot be sensibly expanded without cause. Artists often speak of standing on the shoulders of masters, that is because we have a history, not remotely that art historians convey. Art history for artists should be taught by artists. The art historians version is for consumers and mostly like Rembrandt scholarship, grossly misleading. Considering I pointed out the failures in my article in The Burlington Feb.1977. One has to be extra generous to overlook the criminal mis-information that is still taught in high places.

I have written a lot about the alternative tradition because on the whole it is neglected. It is based on Roman geometry, which developed as a result of making copies of terracotta portraits or Greek sculpture. It is a three dimensional geometry, developed from a measuring boss on the sculpture itself that leads the mind of the artist towards the Platonic solids, resulting in a more accurate description of the visible world. It is present in the major works of Masaccio, Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas, Giacometti and many lesser names. Rome has had a bad press since Wincklemann but if you understand my point about these artists you will see that the bad press is horribly undeserved. My discovery that the most revered works on The Parthenon are in fact Roman restorations adds considerable weight to this argument. See link to A Sculptor’s Perspective.

The two traditions of form, the Greek and the Roman have dominated western art. The modern obsession with originality, that is in truth no more than novelty, is actually undermining the time-honoured visual language, which was used for telling religious stories also to the illiterate. The arts of drama and dance contribute alongside sculpture, painting and drawing to the refinement of that language. It was universally comprehensible because it was the same body-language that teaches us to navigate life itself. Art cannot tell valuable stories without the human body. “History Painting” as it was called, was once regarded as the highest form of art and should remain so; the rest is decorative, life-enhancing maybe but not central to human cooperative existence.

What I am saying is that all these arts had a beneficial effect on human communication that has been neglected by the modern preference for abstraction in the arts. This has done incalculable damage to inter-human understanding. Our universal, non-verbal communication is obviously in steep decline.

Prepare for the massive changes in art history that will result from recent discoveries

by studying with Nigel Konstam at Verrocchio

My encounter with Prof. Ernst van der Wetering, heavy weight champion of the Rembrandt world, was over all to quickly. See my blog www.verrocchio.co.uk/blog TRIUMPH OF TRUTH. Though the discussion was all on his territory (the two Adoration paintings) he did not even seem to understand the difference between a cartoon reversal and a mirror image and therefore was unable to understand his crushing defeat. (A mirror reverses a different view of the same group one observes direct. It therefore proves the presence of a three dimensional group for Rembrandt and his students to observe; the student versions prove the same.)

If there is another heavy-weight out there who thinks he could do better than Van der Wetering I am very willing to have a return match in front of a primed audience containing a fair smattering of people who can think three dimensionally, such as artists, engineers or architects. My fees would not reflect the fact that I am now the reigning champion, though naturally I do not want to end up out of pocket.

SERIOUSLY, Rembrandt scholarship has been in a disastrous state for too long. The scholars will never willingly concede defeat. I have been criticizing from the side-lines for 43 years without effect. The public or the media will have to intervene to arrange this confrontation before I go the way of all flesh. (I am now 87)

I have wonderful news to give the world if I could get a word in edgeways. I am in the process of revising my 1978 book on Rembrandt which was accepted by Phaidon and then rejected after a heinous reader’s report from an anonymous Rembrandt expert. Is there a brave publisher out there?

This is an attempt to show how my discoveries should alter our assessment of Rembrandt’s character and the extent of his corpus in major ways. I accept what his contemporaries said about Rembrandt, the scholars pursue their post-photography ideal of ‘invention’ as the prime quality of art. Rembrandt ‘produced’ his tableaux vivent to work from but he put his chief creative effort into observing the expression of feeling in his drawing, which of course involved memory of his life’s experience. Groups of life models cannot maintain expression for the time the artist needs to complete a drawing. He presumably posed his models with care but he then interprets their inner thoughts brilliantly relying on memories of experience.

Truly horrid things have been said about Rembrandt in the press as a result of recent scholarship. For instance in the New York Herald Tribune. “Rembrandt was a money-changer in the temple of art”, followed by a whole paragraph of hostility. In the same year 1991, when the 3 major exhibitions were taking place to establish the new scholarship he was compared more often with Andy Warhol in the press than with any other artist, for his business procedures based on the erroneous idea that he ran a huge workshop churning out his recently dismissed works, signing them and selling them as his own. In fact though such practices were normal in Rembrandt’s time, he was determined to paint every stroke himself. The experts can find no other hand but Rembrandt’s in “The Night Watch”. After that success he fell from favour in the market-place so there was no temptation to do otherwise with later works. Rembrandt ran an art school not a workshop.

The whole idea of Rembrandt’s Workshop is a recent invention, you will find no reference to it before 1968 when the RRP started work, its a fabrication. Rubens had a workshop of a few very gifted assistants because he was catering for the whole Catholic world in a post Reformation crisis. He was amazingly gifted and with an enormous market gasping for his painting. Rembrandt, a contemporary, was the other side of the coin altogether. He would have loved to be in Rubens’ position but the protestants had no use for “idols”, they were busy breaking them up. He sold more self-portraits than religious subjects but his ambition to be a history painter and his special gift for seeing how we humans express ourselves physically could not be denied. The Bible was his main source of inspiration throughout his life. But I guess when the “experts” finally revise their ideas about the dates of his drawings, fewer group subjects will be found after his peak popularity c.1642. Before that he had access to many models and many students to help pay for them.

Rembrandt himself rarely if ever painted still life or landscape though he made many beautiful drawings of the landscape around Amsterdam. Otherwise, his painted landscapes were nearly always just as a background for human subjects. On the one occasion when he was asked for a landscape he had only a student’s example in stock and he answered the request in a straightforward manner saying “with a few touches from me it could pass for a Rembrandt”. The idea that he would accept student work on his own is outrageously far fetched.

I have shown how mistaken is the designation of his reworking of his own drawing of Job and his Comforters as a student work corrected by Rembrandt, downgrades a drawing which can teach us much and correct our assessment of his character. Link

I believe in over 2000 drawings by Rembrandt. The specialists vary but have recently reduced his output drastically; for instance Otto Benesch’s catalogue of 1954 contained nearly 1500 but today’s scholars – P.Schatborn (recently of the Rijksmuseum) believes in only 500, Professor Slive emeritus of Harvard believes in c.800. How is it possible that these experts vary so widely?

The answer is very simple, the establishment experts believe that stylistic analysis is scientific. I believe that stylistic analysis is hugely mistaken. It is true that in handwriting one can recognise the person whose writing; writers are working with letters which they have used thousands of times and it doesn’t matter truly whether they are using a pencil, a ball pen or a nib the way they would form a letter will always be more or less the same. Writing music Mozart wrote semiquavers in a way that is different from Beethoven’s and recognisably different. Unfortunately with art it doesn’t work the same way. Perhaps we are always drawing hands but all hands are different, they may all have five fingers but seen from different points of view they vary enormously, also according to the age of the subject and so on. Van Dyck was famous for his hands Illust.1. they are always very aristocratic. long fingers, very elegant and always more or less the same. Probably not one in a hundred aristocrats had hands resembling these but most would have wishes for them and would pay well for receiving their attribution.

Van Dyke Hands

Rembrandt, however, is famous for the breadth and precision of his responses. His hands are incredibly different from one another; they vary not only with the age of his models but with the instruments he uses which will deposit more or less ink as he draws on papers with varying absorbencies. Naturally the marks made are different and the shapes wonderfully varied according to what he is observing at the time.(hand of plait 2), If the subject was momentary, the hands suffer.(naughty boy 3)

Here the hands holding the plait are Rembrandt at his very best, so specific and unique.

Rembrandt - naughty boy. The pose is wonderful but the hands minimal.

Artists tend to admire the variety of his responses and tend to be bored by Van Dyke’s stereotypes while still admiring their elegance. Rembrandt has suffered enormous loss in the last 50 years because the experts want Rembrandt to be consistent; he was not. His contemporaries all tell us how unreliable he was and his etchings demonstrate the truth of this. But the writer of the catalogue, Otto Benesch claims he could date a Rembrandt drawing by style to within 1 or 2 years, 3 at most. The marketplace is impressed by this boast. I am appalled; in fact I have proved beyond reasonable doubt that Benesh’s method of dating drawings is completely at odds with the facts. As the advertisement for my talk at the Wallace Collection states “Konstam’s discoveries have proved surprisingly controversial considering that they agree entirely with the documentary evidence of of Rembrandt’s own contemporaries and earlier connoisseurship. They are clear and obvious to the layman observer. It is today’s scholars that are out of step.”

I have shown how Rembrandt responds to the different stimulus he is working from. If he is working from life under his control he can take his time and sometimes draws hands unbelievably skilfully. (Hagar4).

Hagar meets the Angel - beautifully drawn hands

Sometimes life in the street. The Pancake maker is not under his control so his hands become pretty wild.

Street vendor - Pancake maker

If he’s drawing from a mirror (hand from mirror image 6)

Abraham's hands observed in a mirror

which he has done at least 100 times in my estimation we can expect the result to be a great deal less interesting than when he is responding to life directly. All this is common sense, it should not surprise us. But the marketplace would like Rembrandt to be reliable, in truth the quality of his drawing is more varied than any other great artist I can think of – as demonstrated here.

The experts think he was drawing out of his head almost all the time. I know that he was drawing from life whenever possible. His contemporaries tell us “he would not attempt a single brushstroke without a living model before his eyes” that could hardly be clearer. Why have the experts decided the opposite? When he didn’t have life in front of him his imagined drawings are very different and inferior (see Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis 8 whole). The worst drawing certainly by Rembrandt because his writing on the drawing tells us the story that the drawing itself fails to convey..

Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis

When he had life in front of him his results also varied enormously and unlike Michelangelo he didn’t seem to mind leaving behind some very inferior drawings for us to puzzle over. Rembrandt varies from exquisite to quite banal or careless as a draftsman; that is why I can believe he produced very many drawings of which over 2000 still exist today. We know he had students who drew from the same reality he set up to work from himself but fortunately none of his students drew remotely like him; some of them were reasonable draughtsman, none of them approaching greatness.The confusion is of the scholars making. The trouble is the experts recognise excellence in Florentine Renaissance art and are disappointed in Rembrandt’s genius because it is not the same. Where the Florentines were great at the nude physique Rembrandt is interested primarily in what is going on in the head/heart of his subjects. I cannot agree with Houbraken that “his female nudes were such pitiful things that they are hardly worth mentioning” but I can easily understand why he said it. I therefore question the recent de-attribution of a few mediocre drawings which are clearly of Rembrandt’s mistress Hendrijke, one of which is a preliminary study for a famous etching! The Arrow Holder.

My method of assigning drawings to Rembrandt relies on identifying his style of form making that is based on three dimensional geometry derived from Rome rather than from the Florentine method, Greece.. I don’t care if he makes a blot or a mess in his drawing of “The Deathbed of David”

Deathbed of David

because two-thirds of the drawing is so superb as illustration and typical in form it could not possibly be by one of his students, nor for that matter by Van Dyck. Only very rarely am I in doubt as to whether a drawing is by Rembrandt or by someone else because his work, good or bad, is on a different plane all together. By accepting as justified the critical descriptions of Rembrandt’s work by his contemporaries I have no difficulty in accepting some mediocre drawings by him (see Harsh Criticisms below).. Our experts alas, see the faults but do not seem responsive to his genius. They have little understanding of his style and less of his character or enthusiasms, they regard the mention of human interest as ‘unscientific’. No wonder they have missed Rembrandt to the point of madness. It is pointless to expect Rembrandt to behave like the classical masters. He is the first of the moderns; he was living through the revolution that has created modern science, Rembrandt has changed art in a similar way- by confidence in his own observations rather than in artistic tradition.

Rembrandt spent half his creative energy on a subject matter which from a market point of view was a non-starter in protestant Holland. He painted what he wanted not what the market demanded. We don’t even know to which protestant sect he belonged. He got involved with the Calvinists because Hendrijke, his partner for 17 years, was accused by them of living with Rembrandt in concubinage. He did not show up at her trial, maybe he had become a Mennonite by then. We can surmise that he was a believer of some kind but there are good reasons for him to be involved with Biblical subjects other than belief:

The Bible was the best known book of stories of every kind, read throughout Christendom and beyond. It had recently been translated into most of the languages of Europe from Latin, Greek or Aramaic and so was hot news for most Christians. The sheer richness of the human subject matter was a gold-mine for anyone interested in investigating the human psyche. The only other possibility for the same mining was classical mythology, which he used occasionally. But it did not have the same popular following. Ovid was for the scholarly few.

Rembrandt does not compete with Rubens, Van Dyck or Hals in swiftness of execution; he goes his own way at his own pace, often remarkably slowly. The experts like him to be making bold strokes,often these are a last resort to make clear second or third thoughts.. Rembrandt was a true artist seeing life as truthfully as he could, without embellishment. He is very much a man of his own time insofar as he is following the example of the great scientists who refused to take Aristotle’s word for how the physical world works, they too observed for themselves. That is why many artists regard Rembrandt as the one old master who speaks to us moderns directly. Other old masters we can admire but there is not that feeling that we are in the same business. Rembrandt is the beginning of the modern era in art as Copernicus, Galileo and Newton are in science.

The scholars want him to be the same as the older masters; he is not. They seem to have no idea of his originality. To read recent scholars is to get no guidance as to why the rest of us admire him so much, its as if they need to pigeonhole him and in so doing, rob him of his unique position in art. They are looking with a narrow focus without understanding; they want to know which works are his without any discrimination as to which are better or worse, a distinction of most interest to the rest of us.

I offer a rational explanation for his variability – the scholars seek to explain it by the development of his style. They talk in special jargon to put their folly beyond common sense criticism. Rembrandt relied on observation more than most. He did not believe in invention and made that plain when he was obliged to invent: (flying angel).

***************

Panowski recommended art historians should not fall in love with their subject; reasonable advice but it has been followed to the annihilation of any kind of appreciation. Scholars are afraid of making judgements that will not last. Nothing lasts in man’s restless view but its necessary to make judgements to guide our own present effort. I regard Rembrandt as the most important artist ever and I am fully prepared to tell you why.

Rembrandt was following Caravaggio’s example in a general way, there were several Caravaggists in Holland at the time. In this he was merely following a trend. When he set up studio in his home town of Leyden with his younger but more experienced partner Jan Lievens, he was clearly the junior partner in quality but from those inauspicious beginnings he rose rapidly. He acquired the technical mastery of Lievens and surpassed him in vision in 2 or 3 years. His painting of “Judas Returning the 30 pieces of Silver” was noticed and praised by Huygens as better judgement and taste than Lievens. It is highly dramatic and set Rembrandt on his way towards the expression of human emotion which was to drive his art for the rest of his life. Interestingly it is the first of his paintings that we can recognise immediately as the Rembrandt we know from his subsequent output. His earlier work is quite different and amazingly inferior.

Judas returning the 30 Pieces of Silver

I am going to describe Rembrandt’s originality in somewhat different terms to the usual praise of his mastery of light or his broad brushwork which are admirable but not crucial. Rembrandt bought and studied no fewer than 30 Roman portraits. They were much sort after and therefore very expensive. He filled two books of studies of them. Kenneth Clark finds him lacking in taste in doing so because Roman work has been consistently disparaged by art historians since Winckelmann. This is a huge mistake in my view; half the artists of Europe use the three dimensional geometry found in Roman portraits as the form base of their work: Masaccio, Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas and Van Gogh to name but a few. Most use it as the method of suggesting the three dimensional nature of solid objects, Rembrandt went further and used it to define the space between his protagonists as well. By this means coupled with observation from live groups, he has a control over space relationships which is uniquely precise. It is the way in which he conveys drama or psychological relationships; his particular gift.

Normally artists use pespective to define space, and if you are constructing space this is the only way. But Rembrandt was observing space from tableaux vivent he set up for himself and his students to work from. The creation of the tableaux was an important part of his art. His student Hoogstraten tells us as much, yet the experts think its more exciting if artists imagine it all. Alas, artists never make so good a job of intimate space by construction as Rembrandt did from observation. It is another of his original insights that space needs to be observed. I am sure he would not have described it that way himself, consciousness of space perception is a recent 20th Century notion but Rembrandt was the the greatest practitioner. Giacometti introduced me to the importance of space, his obsession; but he did not use it with the psychological insight of Rembrandt. It is the most important artistic insight in my life-time. It has driven my approach to criticism.

Perspective is useless for depicting intimate space, just about OK for theatrical space. This is the foundation of Rembrandt’s genius, The experts continue to deny the existence of the tableaux now 40 years since I prove them by pointing out that Rembrandt not only drew them direct but on many occasions made drawings from their mirror image, that is a different view reversed of the same three dimensional group. See Rembrandt’s Adoration of the Shepherds. Of course these groups existed. This is another embarrassment for scholars who have filled library shelves with books on the iconography of Rembrandt and his school; where I see the differences of treatment largely as simply difference of physical points of view of the same group subject, student and master working together looking at the tableaux from individual viewpoints, they are primarily physical difference not differences of interpretation. The scholars’view that students worked from Rembrandt’s drawings is totally impracticable – Rembrandt himself never did it but scholars are determined that Rembrandt imagined and his students followed after – because Benesch told them so. All the evidence is with me, not with the scholars.

Rembrandt used his drawings to feel his way into a subject in a general way there are no preparatory drawings such as one finds in Renaissance masters. Rembrandt is capable of making over 20 versions of the Hagar story and then a painting which has almost no relation to the drawings. I would date all around 1637 the date he wrote on the etching-plate; the scholars refusing to take note of Rembrandt’s use of mirrors and chose to believe he returned to the same subject throughout his life! Rembrandt explicitly rejected as “worthless” anything that was not observed. All the evidence favours the fact that the group was assembled in 1637 and may have been present in the studio for several months perhaps in part even years as his students made big important painting from them. (link Hagar video)

In my explanation of the National Gallery’s version of The “Adoration of the Shepherds” a small painting of a large, varied group of humans, animals and architecture seen from a different point of view and reversed by the mirror but of the same group as posed for Rembrandt’s Munich painting of the same subject (see YouTube link). This is a proof as clear and beyond dispute as checkmate. Yet the experts take no notice, they continue their destruction as if all was as they have been told. Furthermore, their belief flies in the face of all the contemporary witnesses who tell us over and over again that “Rembrandt was taught by nature and by no other law”, or words to the same effect.

My work has been endorsed by quite a few scholars. Prof. Sir Ernst Gombrich insisted that it got published and his name appears on the original article in The Burlington Magazine (Feb 1977) as having helped me to formulate it. The maquettes from my exhibition at Imperial College were reviewed by Prof.Bryan Coles with the words “ some of which compel assent”…. “it would be a pity if scholarship did not profit from his imaginative researches” (see also the list of eminent supporters link) But alas, these proofs also make the scholars look foolish, so they ignore them.

I do not have to believe Rembrandt was a perfect human-being or a consistent artist in order to venerate him. One of the most endearing features of his work is his total acceptance of life as it happens. There is nothing of the hubris that led Michelangelo to destroy his preliminary studies or his misadventures. Rembrandt has left us an entirely unedited version of his production. I know of no other artist who went out of his way to show how anything imagined “was worthless in his eyes”. Most of his flying angels are drawn with a deliberate worthlessness. No worries about his inability to imagine the scene of Jupiter’s visit to Philemon and Baucis 8. He is practising what he preached – his valuation of truth above all – see also the etching of Diana, a truly hideous version of the virgin goddess from a young man out to make a point about truth.

Diana by Rembrandt, a provocative view of the virgin goddess

The ‘Unreliable’ Rembrandt

I agree with Gary Schwartz “the study of Rembrandt has much to gain from the serious consideration of the negative criticisms voiced by his contemporaries.” and they do not find Rembrandt at all reliable or consistent.” Benesch’s error is pure wish-fulfilment that has resonated with his heirs and followers.

By his study of the documents Schwartz brings into question many aspects of Rembrandt’s character that suggest his untrustworthiness. He was struck out of his sister’s will and his wife’s will, he was never asked to be godfather to a child, “he himself sabotaged his career” says Schwartz – I take all that on board. I think you will find below good reason to view Rembrandt’s behaviour as highly erratic.

Supreme self-confidence does not normally sit well on the shoulders of an artist. But Rembrandt’s confidence in his own judgement is the foundation of his ability to push art in the direction of truth above conventional beauty; it has earned him everlasting fame for very good reason but it caused no end of criticism in his life-time and again recently.

Von Sandrart tells us that Rembrandt “had no understanding of the importance of social rank “it is certain that had he been able to keep on good terms with everyone and look after his business properly” he would have made a fortune. Baldinucci writes that “not even the foremost monarch on earth could gain an audience but would be sent away until Rembrandt had finished his work”. The Prince of Orange had to wait fourteen years for the last of his Passion series. The painting arrived still wet and the Prince paid only half the asking price. The Sicilian nobleman for whom Rembrandt painted several portraits sent back two complaining that he had bought work from Italy’s most famous painters and never paid so high a price nor received work so ill completed (his portrait of Alexander the Great was sown together from four pieces of canvas).

Rembrandt’s dealings with commoners took a similar pattern. His quarrels with his first mistress and with Saskia’s family after her death show us a man who was lacking in diplomacy to say the least. There are stories of him painting the corpse of his dead monkey into a commissioned family portrait and keeping the painting himself rather than removing this nasty, unwanted addition.

Harsh Criticism

There are constant complaints from his contemporaries such as “he did not finish his paintings properly – it is rare to find in Rembrandt a well painted hand – his female nudes …etc. Rembrandt answered these criticisms with “a picture is finished when the artist has expressed his intentions in it”. It is this clarity about his intentions and their revolutionary nature that makes Rembrandt such an important example to artists. His female nudes are not idealised as was expected at that time. They were shockingly unglamorous and by no means always well done.

All this evidence needs airing. On occasion I think Schwartz has taken an over-negative view of the evidence. For instance he says of Rembrandt’s relations with his students “the few stories that have found their way into the sources are not heart-warming at all.” He also finds Rembrandt humourless and miserly. Houbraken tells stories which suggests quite the opposite to me: Rembrandt comes upon a scene where his students are eavesdropping on another student and his model locked together in the student’s room. He overhears him say “here we are naked like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden” at this point Rembrandt bangs on the door and shouts “Because you are aware of your nakedness you must come out of the garden” and then chased them down the stairs with his stick, I guess as theatre, because “they scarcely had time to dress as they fled”. On other occasions students painted coins on the floor in order to see him stoop to pick them up. This suggests to Schwartz that Rembrandt was over attached to his money. To me It confirms that he had a playful relationship with his students some of whom stayed with him for many years though he charged twice as much for an apprenticeship as his rivals. There are many references to Rembrandt’s generosity in lending objects from his collection to painters who needed them. Generosity again In paying over the odds for works by his contemporaries to boost their value and paying extravagantly for works of art generally; he was profligate as well as generous. When he had money he certainly threw it about. His great house proved much more than he could afford but that was as much bad luck as bad judgement; he lived through a severe recession in Holland caused by war with England. Fashions in art change. Rembrandt like many others found it difficult to adjust.

Rembrandt changed the course of art. He seemed so completely immune to criticism that it might help us to understand him better to take these aspects of his character into consideration. If scholars realised they were dealing with a man who exhibits many of the symptoms of Bipolar behaviour, they might treat him more kindly and abandon their efforts to normalise him. They want him to be consistent, he was not; and we cannot understand him unless we take his inconsistencies into account. Some were psychological in origin and some were physical. The difference between Rembrandt’s drawing direct from life and when he relied upon a dim reflection in a polished metal surface, or even worse when he relies on his imagination, is very obvious but at present overlooked by the experts. (for examples, see my ebook www.nigelkonstam.com)

These stories and complaints should surely alert us to the fact that Rembrandt, great painter as he is, was not an entirely reasonable human being. As Bernard Shaw noted – “The reasonable man adapts….All progress depends on the unreasonable man”

I am no psychologist I would like to hear what professionals think of this evidence. Rembrandt’s behaviour, his output, his charisma and his supreme self-confidence all seem to me to point to manic-depression. But there is a miraculous quality to his best drawing that is beyond compare. Those who know the genius of Stephen Wiltshire’s memory may have some idea of the level to which Rembrandt’s memory and manual dexterity supersedes all save Stephen. He seems capable of catching a passing event such as this flash of anger (3) as if there is a photo in his mind to which he can return many times after it has passed, to recapture it on paper. Stephen can spend a fortnight drawing a city-scape from the memory of a casual glance from a helicopter; Rembrandt may have had a tiny fraction of that magic.

There was a famous teacher who devised a method of improving visual memory, Lecocq de Boisbaudran. It produced some excellent results but has fallen into disuse perhaps because artists have lost sight of the need of even very short term memory between looking at the object and reproducing it on paper. Lecocq’s method was to remember a Holbein drawing and then reproduce it from memory.

The results were stunning because one cannot remember a Holbein without absorbing his pattern of form making. His heads are universally admired so it is little wonder that Le Coq’s students included Rodin, Fantin-Latour, Dalou and many others. An amusing recent experiment compared an ape’s visual memory with a human’s; the ape’s was incomparably the better. We have clearly lost something as we have climbed the evolutionary ladder.

I hope you have been persuaded that Rembrandt is not the inventor the experts imagine but an observer who responds more truly to that arc of experience which concerns us humans most. We must save Rembrandt from the experts before it is too late.

Blogs and videos at www.nigelkonstam.com

Practical Art History courses www.verrocchio.co.uk

• RE-IMAGING THE IMAGINATION

The theorists of art suffer from the mistaken but widespread idea that the imagination takes place in the mind, mainly of homo sapiens. Most visual artists will recognise that their imagination is greatly enabled by playing with the materials of their art in the real world. This aid is particularly obvious in the three-dimensional art of carving. The popular image of the carver, prompted by art history, is of an individual who is capable of imagining the finished figure in the block and then removing the unwanted stone. I used to shared that view.

• Now I start my carving from an amorphous piece of alabaster, selected because it’s volumes appeal to me. Initially I have no idea what I will make from it. I start by clarifying the movement in the stone that attracted me; I also clarify the volumes, cutting away jagged pieces that can never be useful. By the end of the first hour of work, turning the peace over, regarding it from every point of view I usually have some idea of what it could become. Some of those ideas are rejected because they have no appeal.

• From an overview of my works it is fairly obvious that the female figure attracts me so in the majority of cases I block out a figure that could change sex or position because I sketch it with the maximum gesture the stone will allow. This is my preferred strategy; if I am constricted by a specific commission (a rare occurence) I would start by playing with wax or clay. In either case the very slow process of freeing the figure from the matrix of stone inevitably presents me with a sequence of slow moving, vague figures which allow the imagination many possible directions and outcomes.

• The subject matter of my carvings is more varied than that of my works in clay because of this constant feeding-in of new possibilities. Their comparative permanence is also helpful. These varying possibilities must exist in clay but are quickly submerged by the conscious will of the artist driving towards a fixed aim; in carving they may persist for weeks.

• The poet, for eons regarded as the one true artist, plays with words – abstractions. But for the visual artists, including actors, dancers, architects, engineers and painters, their imagination is hugely aided by acting out – making real movement in the real world.

• Because memory is the basis of the way we interpret the world about us it is not possible to quantify how much of imagination is purely mental. My point is that the visual critics generally discount the input of reality, believing that the imagined is somehow superior. Rembrandt scholars may feel they are doing him a favour by denying the existance of the groups of models that posed for him. But in fact the scholars are doing him and any artists who might choose to follow his example, a huge disservice. They are putting Rembrandt’s putative achievements far beyond human capacity.

• Anyone who believes computers will never equal human imagination should think again. A machine that can put an individual name to 500 million faces even when seen from varying view points, will very quickly outstrip the human imagination. It just needs to understand the function of imagination. Far from being a rare human attribute; imagination is an essential part of the animal survival mechanism – that lion ate my brother, therefore this lion may eat me.

I have given 3 tours of the Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum to demonstrate the evidence that the most often praised and photographed of the sculptures are not Greek but Roman replacements for the originals probably done 570 years later. Richard Payne Knight, a connoisseur and MP, had the same idea at the time Lord Elgin was selling his collection. He was disgraced for his presumption but I have concrete evidence that he was right. My evidence is easily appreciated by the untrained layman because the Greek work is discoloured by smoke from a chimney I discovered and published in The Oxford Journal of Archaeology in 2002. I am to contribute to a Plaster Conference on the 6th & 7th of April 2020 that has been described as “having the potential to revolutionise the entire field of Greek and Roman sculpture”. Here is the script of the tours. The quotes from Roger Fry and Keneth Clark are important to understand just how far modern criticism has strayed from the preferences of Rembrandt, who owned 30 Roman portraits and filled 2 books with studies of them. A revolution in art is well over due.

A Tour of the Elgin Marbles

Good morning, I am Nigel Konstam, a sculptor/bronze caster, not a classical archaeologist so I see these sculptures from a different viewpoint to the archaeologists; with much more practical knowledge of the processes involved and perhaps less mythology in my education. I do not come to these famous icons of art with the same weight of traditional opinion as the archaeologists. Nor am I here to devalue these great works but I do hope to persuade you that the people responsible for the better half of them are not the Classical Greeks, as is generally supposed, but Romans. This is hard to accept for those who know their art history but I expect to convert you all within a few minutes.

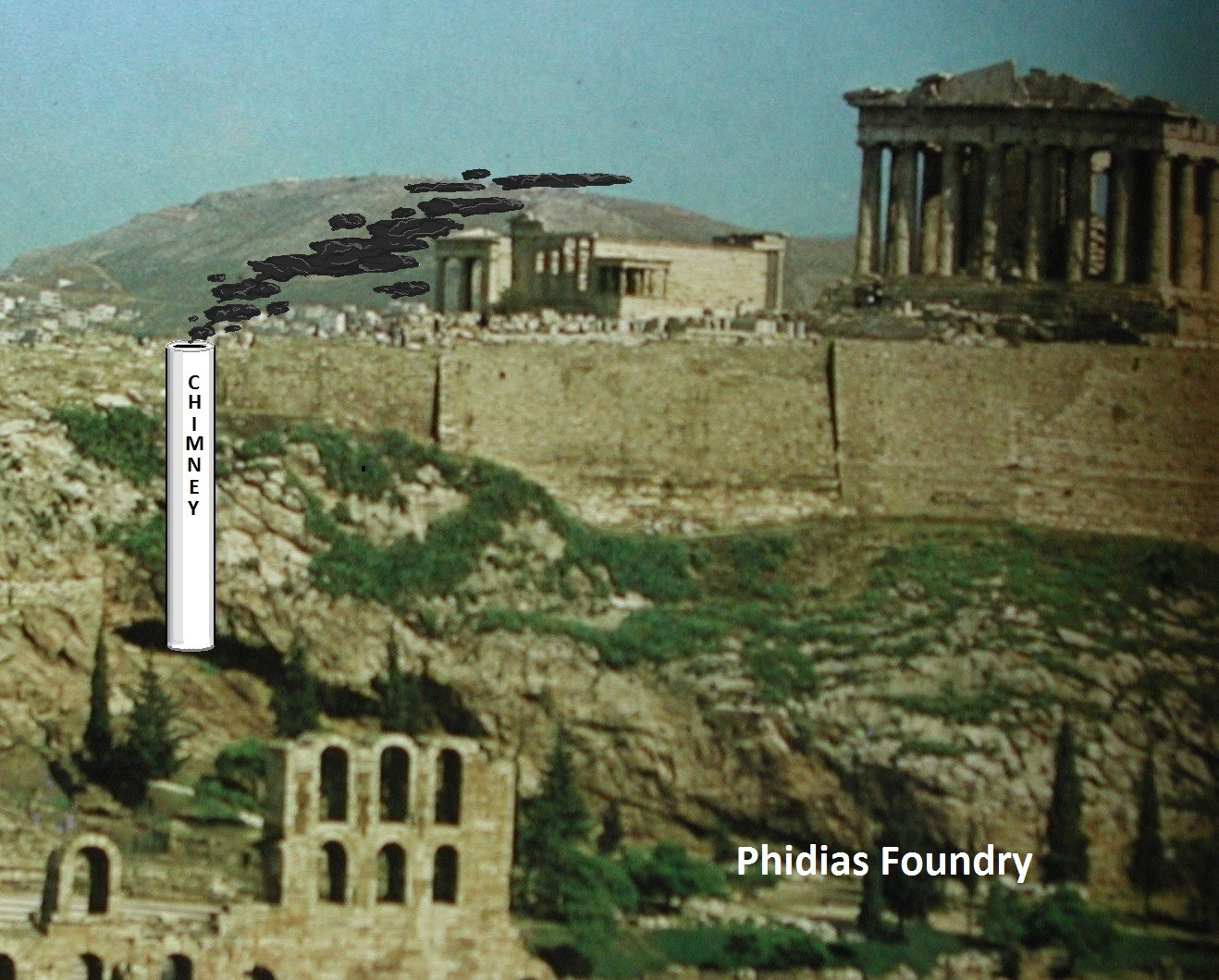

In the year 2000 I was lucky enough to discover an ancient chimney on the Acropolis Rock in Athens used by Phidias, the sculptor in charge of the works on The Parthenon. He used the chimney for melting bronze for his gigantic bronze statues. I have recently come to believe this chimney was responsible for an industrial scale smoke pollution which I hope to demonstrate today was responsible for ruining the west pediment with more than 500 years of acid rain. My dicoveries were published in The Oxford Journal of Archaeology in 2002 and the site in Athens is now signposted as a chimney.

We are here in a gallery full of sculpture from The Parthenon the sculptures were brought to Britain by Lord Elgin and so they have the local name of “The Elgin Marbles”. All were taken off The Parthenon, the most famous Greek Temple built by Pericles in Athens starting in 448 BC. The original sculptures were completed in 432 BC. We are in a perfect place to assess most of the evidence of smoke damage.

We are circulating a page of photographs of the evidence we cannot see today because it is in Athens. It is relevant to my thesis – the thesis being that the whole of the west pediment and “The Horse of Selene” on the east pediment are in fact Roman replacements for the original Greek works which had been ruined by smoke from the Athens chimney. I am not the first to suggest Roman workmanship but I am the first to explain how that came about. The evidence of smoke is very easy to follow, the evidence of style which comes second may be slightly more difficult for those untrained in these matters.

Figure 1 – This shows the relationship of the chimney to The Parthenon. The chimney emerges about 150m down wind from the west facade. The west pediment would therefore have received the full brunt of the weather and smoke driven by the prevailing south-westerly wind. Even now after extensive cleaning and repair there is plenty of evidence that The Parthenon was once blackened by smoke. John Boardman, a well known classical archaeologist was looking for a source of pollution for The Parthenon – I found the chimney and as a result finally came to the upsetting conclusion that many of these works are excellent Roman replacements for the original Classical Greek works.

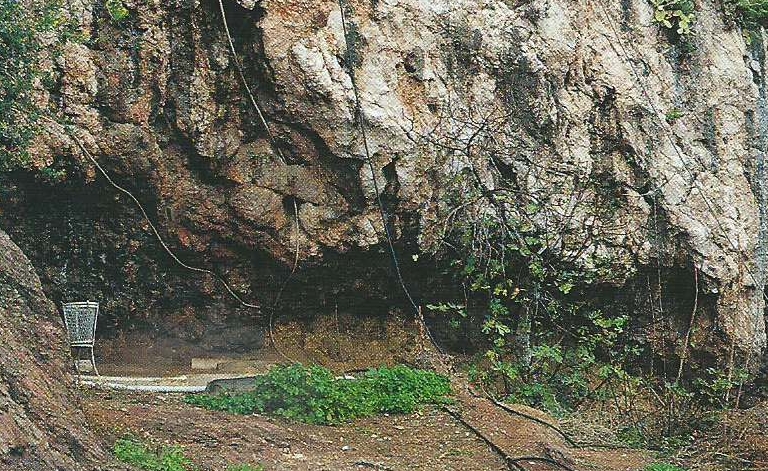

Figure 2 – This shows the upper west end of the diagonal C section cut in the Acropolis rock which I discovered, it is full of soot and tar throughout its length and discoloured orange by heat. Interestingly at the top end of the existing chimney-section the signs of smoke disappear. I therefore hypothesize there was a vertical tower chimney (represented white in fig.1) that would have taken the smoke yet closer to damage The Parthenon. I have no way of knowing how high the chimney was but undoubtedly a metre or two. Furthermore, if one was designing a building to catch smoke The Parthenon would be a good solution with its outer columns and inner wall making a corridor to conduct smoke along its length.

Figure 3 – This shows the passage of smoke through the Parthenon, mainly high up on the walls and ceiling but particularly along the west and south sides of the Parthenon you will still find blackening under the architrave caused by centuries of smoke rising from below.

Figure 4 – This shows an early photograph of the Parthenon before restoration. We see it is heavily blackened particularly at the west end, and less black around the damage caused by the explosion of the Turkish arsenal in 1687. The Acropolis was being bombarded by the Venetians, the Turks kept their gunpowder in The Parthenon. Naturally, tremendous structural damage was done by the explosion but the pollution would have been short lived. The chimney would have been polluting perhaps for 500 years 1,500 years earlier. Bearing in mind that those pillars have been washed by rain for 2000 years before the photo, we can guess the pollution in Hadrian’s time would have been very heavy indeed.

From here, below the east pediment, I ask you to look at the colour/tone difference between The Horse of Selene (on the extreme right) and the rest of the east pediment. I think you will agree with me the horse is much lighter. If you now look at the west pediment it is all the light colour of the horse. I believe that all the lighter work is Roman replacement of the original Greek designs. If we now go over to the east pediment I will explain why.

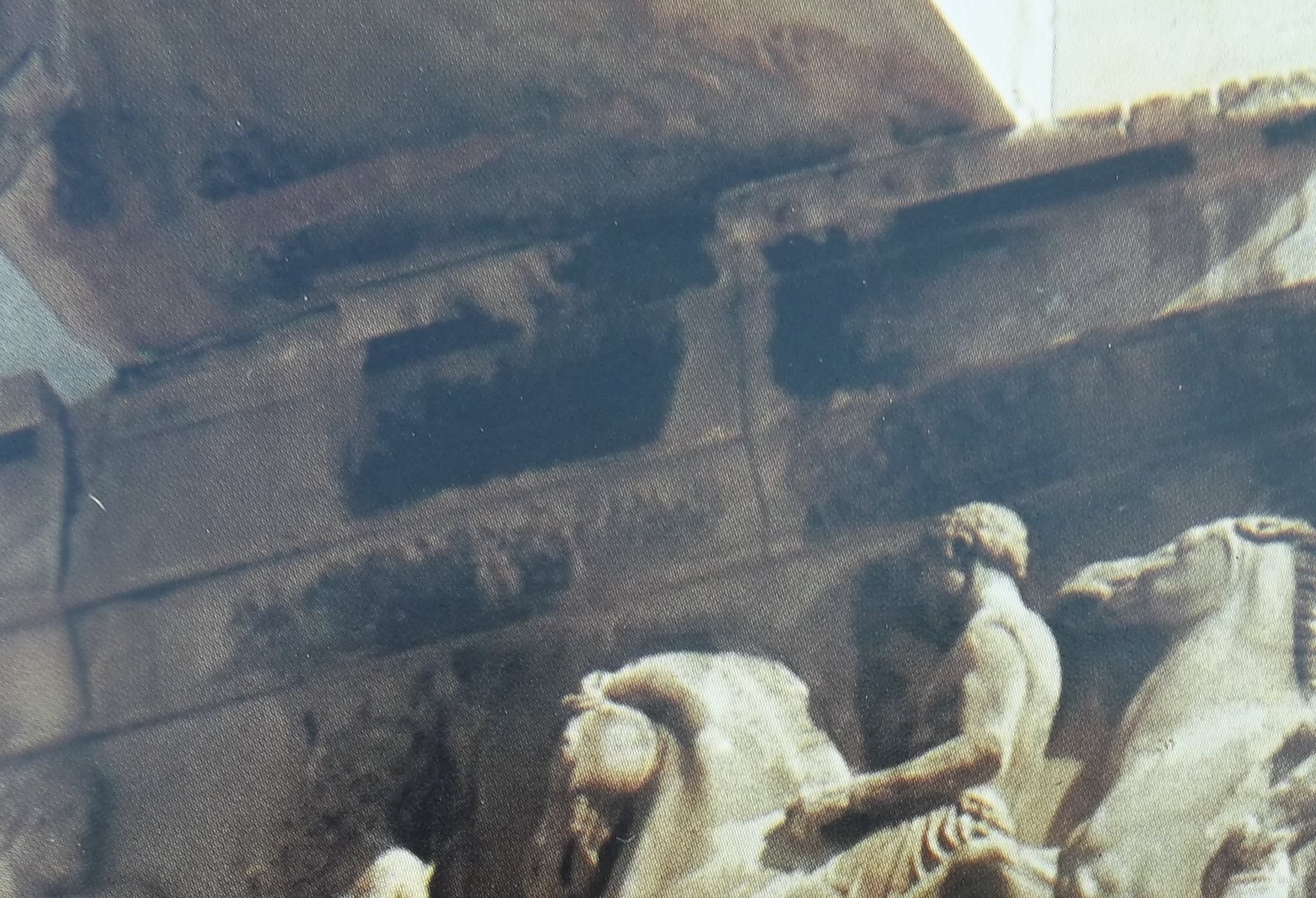

Here we see two very damaged genuine classical Greek horses to contrast with the perfect clean Roman Horse of Selene. We see blackening in many places on this pediment, under the thigh of Dionysos there is even erosion under his knee, from the acid smoke rising from below. On the stool of the two ladies next to him there is heavy evidence of smoke rising from below and depositing soot on the stool, the skirt and legs. If we go round the back we see very heavy deposits of soot that has survived four cleanings (the one here in the museum in 1938 was scandalously severe, removing up to 2 mm of the surface in some places). The reason for the position of this heavy deposit is that in classical times they were carving marble with iron or bronze tools. The fragile nature of the tools confronted with the hard marble meant that they worked very slowly pecking away at right angles to the surface but this had the effect of bruising the marble beneath. That is the crystalline structure was disturbed creating crevices which allowed the smoke to enter deeply, well beyond the reach of any scouring. Working in this valley between the cloth of the sleeve would have been more difficult and therefore created more bruising and more penetration.

Figure 5 – Horse of Selene (right) compared to the greek original (left)

Figure 6 – Damage caused to sculptures in the Parthenon. One can see on the knee of Dionysos (right) a dent at the top where erosion has taken place; also the parallel ridges on the thigh suggest that a layer of black erosion has been chiselled off (probably before Hadrian’s more thorough restorations were undertaken).

Later carving was done with steel tools at an oblique angle to the surface which did not bruise the marble beneath, hence the dark gray of the original work and the lighter colour of the replacements. I guess that these replacements were paid for by the Roman Emperor Hadrian because he had the power, the taste and the willingness being a great admirer of Greek art. I do not insist it was he but at the time of the purchase of the works from Elgin, an art expert who was also an MP, Richard Payne Knight suggested the works were Roman and of that period. He was disgraced as a result, though I now believe he was right. Elgin himself had left two figures, of King Cecrops and his daughter, on The Parthenon because he believed them to be Roman copies.

The reason why the horse had to be replaced although furthest from the source of smoke is twofold. First because the nose and mouth actually overhang the parapet and therefore received the full effect of the rising smoke; and second because the work on the hollowed mouth and nostrils would have undermined the crystal structure severely thus increasing the entry of smoke and the chances of collapse.

Many regard these sculptures as the most beautiful ever made. It is interesting to reflect that what I now believe to be Roman work has been particularly lauded and reproduced as typical examples of Classical Greek work.

We have looked at the most obvious evidence. Before going on to demonstrate the stylistic difference of the Roman work, which is more subtle.

This horse’s head is crisp and geometric suggesting a Roman hand. Let us return to genuine Greek Dionysos in order to compare him with the Illissos figure on the west pediment, which I believe to be Roman, in the Dionysos the forms are more rounded and with little or no sense of the underlying muscle, fat or bone, where the museum’s own brochure describes the figure of Ilissos on the west pediment as “an admirable example of the mastery with which the surface textures of skin, tense or loose, and the underlying muscle, fat and bones are indicated by the sculptors of the Parthenon. I agree about the excellence but not about the authorship. I have always regarded this figure of Illissos as the greatest of all. I particularly admire the way the stomach stretches between the rib-cage and the pelvis and the differentiation between the two thighs, all brilliantly observed. I have described this work as by an earlier Bernini from ancient Rome. Recent scholarship has consistently taken a dim view of Roman art. Roger Fry in his “Last Lectures” as Slade Professor at Cambridge said of Rome “the one great culture of ancient times of which we can, I think, say that the loss of all her artistic creations would make scarcely any difference to our aesthetic inheritance.” I hope my demonstrations have persuaded you that this assessment, is gravely mistaken. It has had enormous influence.

Finally to bring this new truth up to the present let me quote Lord Clark, he spent a page and a half denigrating Rome’s contribution to art in his “Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance”(1966) with such phrases as “what could have persuaded Rembrandt to have drawn these posturing marble divinities – smooth, soulless and inane”. Clark would doubtless be somewhat embarassed to find out that this magnificent piece was in fact a Roman copy.

Unlike Clark and modern taste generally Rembrandt admired Roman art intensely. He owned 30 Roman portraits and filled two books with drawings of them. The syntax of his drawing is deeply influenced by the Roman tradition. Sadly, this modern attitude has led to many major art schools banishing the cast-room, where traditional drawing was taught because that illusive factor “form” has a direct relationship to Greek or Roman sculpture. As a student in1956 the main aim of an art education was to see form.

When we have finished here I hope to have time to explain why this low estimate of Rome goes hand in hand with the destruction of connoisseurship. I will demonstrate my analysis of the three dimensional geometry in a bust of Hadrian, room 70. This geometry, I believe, became the basis of the better part of European drawing. As prime examples of the use of Roman form I put forward Masaccio, Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas and Giacometti.

There are many of my videos on YouTube. If you wish to check out what you have heard today you can visit my website www.nigelkonstam.com where you will find an ebook entitled “An Alternative History of Art” in which chapter one deals with Greece, chapter two with Rome and chapter nine with Rembrandt and many blogs. All suggest a new start with a new, more accurate history for art. We need to abandon the false traditions of Art History that have gone so far astray.

The one big difference between my interpretation of Rembrandt’s character as an artist and the characterisation of modern scholars is that I see him as an observer and they insist that he was an imaginative inventor. Benesch writing in “Rembrandt Selected Drawings” (1947) suggested that Rembrandt drew his biblical subjects from an “inner vision…as if he seen them in reality”. Whereas Houbraken (167 ) Rembrandt’s contemporary writes exactly the opposite he said Rembrandt “would not attempt a single brush stroke without living model before his eyes” and I have found massive evidence in the drawings themselves that 98% agrees with Houbraken. In fact all Rembrandt’s contemporaries say much same.

Benesch was writing in the 1947 but today’s scholars seem in complete agreement inasmuch as they have stuck with his method of dating by style and savagely prune those drawings that don’t fit in with his ideas; where I have proved over and over again that his ideas were founded on the erroneous assumptions oft repeated in his “Selected Drawings” of Rembrandt’s imagination. I gave ample evidence of this in my article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” (Burlington February 77) and have added to that evidence with many videos on YouTube; nonetheless, the evidence has been neglected by the scholars.

My evidence backs up Rembrandt’s contemporaries who all described the character I have recovered through his works. My version of Rembrandt would expand the catalogue of drawings, perhaps 30% over Benesch’s “Complete Drawings” – Benesch believed in about 1500 of them. While P. Schatborn, once of The Rijksmuseum, more recently claims to believe in only 500 drawings by Rembrandt (in the Getty catalogue “Rembrandt and his Pupils”). I believe in approximately 2200 and am scandalised by Schatborn’s judgments.

Though I have not had the lifetime of experience among the originals that Schatborn has enjoyed, I believe that successive generations of scholars have dismantled what better connoisseurship once upheld. My own research has largely been among reproductions. My advantage is my sense of Rembrandt has not been hampered by scholarly opinion. I studied art and have had a lifetime of practice in sculpture and drawing. Rembrandt has been and remains chief among my household gods. I find it difficult to understand how the opinion of theoreticians should trump irrefutable evidence - indefinitely.

Modern scholarship finds it difficult to believe Rembrandt could have gained anything from his study of Roman portraiture. He owned 30 Roman busts and filled two books with drawings of them, which must be a measure of his interest in Roman portraits. I believe his preference for truth to nature over idealised beauty and his use of three-dimensional geometry as a draftsman is due to his understanding of Roman geometric form; a clear preference over Greek idealisation.

There are a number of other failures of recent scholarship which I will outline. But the last sentence of the paragraph above is the essence of my struggle with Rembrandt scholars since 1974. (I have recently experienced precisely the same disdain of evidence from archaeologists over a series of discoveries in Greek and Roman art; the new evidence is centred on The Elgin Marbles, I agree with Richard Payne Knight that the majority and the best are Roman restorations.)

Other misunderstanding in recent Rembrandt scholarship – G. Schwartz finds Rembrandt lacking in humour. But Baldinucci describes him “as first rate joker who laughed at everybody” I am amused considerably by some of his drawings – Rembrandt laughs at everybody in a final self-portrait.

More seriously, scholars want great masters to evolve consistently; and as Rembrandt rarely signed or dated his drawings they have had a field-day of arranging his drawings in a neat order that is absurdly mistaken (see YouTube of The Dismissal of Hagar, where we see that the changes in Rembrandt’s style are produced not by Rembrandt’s maturing but by his changing stimulus from reality to a mirror image). Rembrandt was once famous for his responsiveness, he is the least consistent artist I know; partly because of the wide variety of his responses and partly because he was responsible as a teacher – he believed that “one should follow only nature, anything else was worthless in his eyes” and he is the only artist I know who was prepared to demonstrate “worthlessness” in his own drawings when he could not follow nature (see YouTube “Isaac Refusing to Bless Esau” or any of his flying angels).

In his paintings one can see that he developed towards a looser style in the 1650s; the same is probably true of his drawings but the present system of dating by style is clearly wildly mistaken. I have shown evidence for a considerable loss in quality in those drawings made from mirror images (YouTube North Holland dress and “The Dismissal of Hagar”). This loss is almost certainly due to the lesser quality of the stimulus from a 17C. mirror. Plate glass was invented after Rembrandt’s death. His larger mirrors must have been made of either polished metal or composite mirrors made of small pieces mounted together, obviously a less precise image than life direct. I have suggested a spectrum of quality – the best - from a stable stimulus: from life in the studio – a lesser quality from less stable life in the street – lesser still from mirror images and finally the least successful, when Rembrandt is obliged to construct or work from memory/imagination. These characteristics can be observed in action throughout Rembrandt’s life.

Contrary to the above idea that Rembrandt drew best from a stable stimulus – there are two feeble drawings from Roman busts which are included in Benesch’s catalogue but presumably excluded by Rembrandt from the two scrapbooks mentioned in his inventory, which sadly have been lost. Nonetheless, I would stick with my spectrum in a general way, writing off those two as examples of Rembrandt’s variability. A few of his drawings are truly great others much less so. Alas many of the greats have been dismissed by modern scholarship.

Fortunately the etchings are often dated on the plates, they are therefore a reliable source for examining Rembrandt’s variability. They speak clearly of the same wide spectrum from infinitely painstaking, for instance in the shell of 1652, to remarkably crude in some of the earlier compositions, or fairly slapdash when drawing a golfer from life. My analysis of The Lion Hunt etchings on YouTube makes a clear demonstration of the above.

We have to conclude from the etchings that Rembrandt was unreliable throughout his life. My own rule is – if there is any part of a work that could only have been drawn by Rembrandt then it is by Rembrandt; regardless of how awful the rest might be. For instance I defended “The Finding of Moses” drawing (YouTube) from Kenneth Clark’s de-attribution although I agree with his criticism; because this is a drawing about precarious balance that could only have been held by the model for limited time; it does not have Rembrandt’s usual sense of form. I think my comparison with the Virgin Mary with basket B could confirm my interpretation with forensic tests showing both are done with the same pen and ink.

Further examples of Rembrandt’s drawings without visual stimulus – a drawing of Philemon and Baucis with Jupiter B - a drawing so feeble it would never have been accepted as by Rembrandt without the little note he added explaining what it represented. He must have been reading his Ovid and thought the subject could make a painting but no models were available so he did his best without them. He did make a very different and successful painting of it afterwards. These examples should make it obvious Rembrandt needed visual stimulus to produce of his best either as a painter or as a draftsman; His student Hoogstratten advises “ take one or two of your fellow students and act out the scene, some of the greatest masters did the same”.

One last example the drawing of Job and his Comforters which experts believe is Rembrandt correcting a student drawing. Such an interpretations suggest that Rembrandt was a brutally destructive teacher because he has ruined what was an excellent drawing. I describe it instead (on YouTube) as Rembrandt correcting Rembrandt, or more accurately Rembrandt trying a new interpretation over his own excellent drawing. The experts are unable to distinguish between the master and his students it would seem, I find no difficulty, Rembrandt was in an entirely different class. The best of his students were merely adequate.

One of the enduring lessons students can learn from Rembrandt is that he was unself-censoring, entirely self-accepting no matter what the outcome. He could not have foreseen the kind of scrutiny he gets in the analysis of his “Descent from the Cross” in The National Gallery’s “Art in the Making, Rembrandt” but there is not a hint of the hubris there that one finds in Michelangelo, for instance.

I have made a case for a new, more generous catalogue of Rembrandt’s drawings based on a new interpretation of his character as an artist. If you agree please signal your approval below and ask for action from the scholars. Rembrandt was once the role model for art students.

“Verrocchio” at the Strozzi Palace is a important exhibition because it sets Verrocchio in his artistic tradition – his antecedents as well as his influence on future generations. Vasari describes him as having “a somewhat hard, crude manner” which is not untrue by the standards of Vasari’s day but I would choose much more positive words such as classic, Roman, geometric, observant. Phrases like a meticulous delight in the volumes of nature, dedicated to visual truths, a great draughtsman. Verrocchio was trained as a goldsmith working on a small scale but his ambition grew in scale when in Rome fairly late. He had the misfortune to mature in the long shadow of Donatello and his reputation was later over-shadowed by his star pupil Leonardo da Vinci. But as a teacher he also had many other famous names as his students or followers.

As far as I’m concerned I would reverse the usual judgement and say that Leonardo’s greatest work, his curiosity and inventiveness was strongly influenced by Verrocchhio. There are very obvious influences and habits in common, both loved drawing complicated hair arrangements, both had a wide curiosity about natural appearances, about anatomy, about landscape and most of all about natural forces and how to master them. Both would leave works for a long time and come back to them with a fresh eye perhaps after years. Both found it difficult to finish their work to order.

Verrocchhio died while casting his great final masterpiece The Colleoni Monument in Venice; he was only 50. The great importance of Verroocchio is the seriousness and dedication with which he pursued the physical three dimensional likeness of his subject matter he was a great teacher and a great artist. Sadly the present catalogue follows the normal approach by calling the exhibition “Verrrocchio, Masterr of Leonardo”. This is a shame. The catalogue spends half a page trying to persuade us that his nick-name Verrocchio means winch rather than true eye, which is so much more appropriate. Added to which some of his most impressive works have been attributed to other masters: The portrait of his major patron Lorenzo the Magnificent (still in Washhington) is attributed to an imitator but what a magnificent job the ‘imitator’ made of it – infinitely better than the master himself in his portrait of Piero Medici (included in the exhibition), which is a fairly run of the mill production in a great age of portraiture; while the Lorenzo must be one of the greatest portrait busts ever made. The terracotta putto, an obvious by-product of the equally beautiful “Winged Boy with Dolphin”is attributed to an anonymous student though it has all the hallmarks of the master himself. The high quality of his workshop is well represented.

In spite of these minor disadvantages the exhibition is a wonderful opportunity to re-evaluate a major master, presently undervalued, and to follow the methods of instruction of the leader of the greatest art school ever known. The catalogue admits “he shaped the style and taste of the age of Lorenzo the Magnificent like no other” what more need be said.

–