Venus and Cupid - Bronzino

I have known and admired Bronzino’s masterpiece in the National Gallery, “The Allegory of Venus and Cupid” all my life. The newly opened exhibition at the Strozzi Palace in Florence of Bronzino’s life’s work (80% of his paintings) is very exciting. It allows one to see him in context, by comparisons with his mentor and friend, Pontormo and contemporary Cellini. (The National Gallery painting is one of the few important works not on show here.)

The range of his work is amazing. His portraits vary in quality, I would guess; according to the number of sittings he was able to exact. The faces of the children of Cosimo I are somewhat doll-like but their costumes are painted with the most consummate ‘trompe l’oeil’ skill. This is true of many of his paintings. His attention to detail is breathe-taking. His best hands can compare with the greatest. When you add to this the beauty of his colour, the gorgeous rhythmic texture of his low-relief type subjects, his mastery of mannerist composition generally, the near VanEyk quality of his best portraits – the word ‘genius’ must spring to mind. The sensuality, range and sensitivity shines through the Mannerism.

There is a newly attributed Crucifixion which extends the range of his painting still further. The extreme austerity of the treatment of this much used subject, holds one spellbound. Little wonder it has evaded recognition for so long. It is not typical, yet this most varied painter is surely it’s author.

There is a small book “Bronzino Revealed” which contains a conversation between the experts which helps one to understand the cultural context in which he worked. It whets one’s appetite for his poetry but without sufficient examples. Nor does it divulge the secret of the new varnishing treatment that allows one to appreciate the consummate skill of the painter even though the varnish is so reflective that at times one seems to be looking through glass.

The museum is devoted to the history of the making of art. The museum’s collection has accumulated over the last forty years as a result of stumbling on the unexpected . When I see something inconsistent with my experience – I seek to explain the inconsistency. This has led to a sequence of art discoveries which could bring about a new understanding of art.

Artists understandably keep secrets about their methods to maintain an advantage over rivals within their profession. Centuries later their secrets often remain hidden. This may happen because of our desire for super-heroes – we want to believe in the magical. This museum is about delving into the truth about how things were made, based on the artefacts themselves, questioning the art mythology.

We have concrete evidence that the Classical Greek sculptors did not follow the “proper” art school procedure of observing from a life-model but used a hollow wax cast taken from life. This came as a great shock. It has upset our sense of where we come from. It requires the revision of Art History. By following the clues present in all the life-size bronzes that survive from the Severe and Classical periods we are led to a very different conception to the one we have accepted for the last 2500 years.

Long ago Pliny reported that life-casting was invented by Lysistratus around 350BC but few historians have acknowledged this possibility. In fact my discovery pushes that date back to around 500BC; the moment when the great Greek revolution changed the course of history with the discovery of natural movement: the famous Greek contraposto. We must now see this leap forward, more as a technical advance, rather than a leap of the imagination. Up to that time the Greeks had followed the Egyptian pattern but less successfully than the Egyptians. Their revolution all happened too quickly, in less than 50 years. Nonetheless my concrete evidence, like Pliny’s report, is neglected.

*****

My most important discovery is Rembrandt’s need to have life in front of him when drawing or painting. In the museum we will see that Rembrandt was a different and inferior artist if he didn’t work from life. Rembrandt’s genius is based on his observation of human interaction: body language, which he conveys through his precise observation of space relationships, usually set up in his studio with live models and theatrical properties.

The importance of his use of mirrors is that it shows us definitively how Rembrandt worked . The experts’ ideas about the development of his style are wrong. The relationship between Rembrandt and his students are also gravely misleading.

Though he could not work out of his head, Rembrandt’s imagination was more serious than is commonly meant by the term. Coleridge, a poet who thought very deeply about imagination, distinguished between “fancy”(fantasy) and true imagination. The brain receives the world through the senses but we all need imagination to make sense of these perceptions. Rembrandt made new and better sense of what he saw, psychologically, using his genuine interpretive imagination. If our experts could take Rembrandt’s and Coleridge’s lessons to heart the future course of art and criticism would be of much greater value to us.

Rembrandt is clearly the most evolved artist that has ever existed. Yet we have witnessed a steep decline in his perceived stature because the art historians refuse to revise their time honoured misunderstandings. They rely too unquestioningly on the literature of art, (including the artists’ own self-promotions) and seem unable to interpret the primary evidence, the artefacts.

The subjects covered in the museum are in chronological order :-

GREECE

1. The discovery that the Greeks used life-casting for their life-size figures from the time of Phidias onwards.

2. a chimney on the Acropolis in Athens, and another in Olympia.

3. a method of steaming moulds to recover 70% of the wax usually lost, used at Rhodes and almost certainly elsewhere.

ROME

Roman geometry had an enormous influence on subsequent art that is seldom acknowledged. The analysis of a portrait bust of Hadrian in the British Museum, demonstrates this geometry. Those artists who have used it since are also represented.(Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas, Giacometti)

SIENA

1. An appreciation of the works of Rinaldo da Siena recently discovered under the cathedral.

2. Reasons why the so called “Duccio Window” cannot be by Duccio.

3. The discovery of the dimension of time in Simone Martini’s Madonna of the Annunciation.

FLORENCE

1. The probable use of a polished silver mirror in Brunelleschi’s second essay in perspective.

2. The probable use of sculptural maquettes in conjunction with mirrors by Masaccio.

3. Michelangelo’s use of maquettes for preparatory drawings

4. Cellini’s casting method is demonstrated to be very close to the method of Phidias.

REMBRANDT’S use of live models and mirrors, indicating that his contemporaries knew a Rembrandt that modern scholarship has all but destroyed; an artist whose example is very important to artists who observe life today.

VELASQUEZ’ use of a large mirror from the Hall of Mirrors at the Royal Palace in Toledo for the composition and rapid completion of his most important masterpiece – “Las Meninas”.

VERMEER’S use of two mirrors in conjunction with a camera-oscura as an aid for painting.

———————–

If there were space available in some future museum. I would like to include some of David Hockney’s discoveries as presented in his fim and book “Secret Knowledge”. He is another artist who has made a very considerable contribution to the true history of Art. I found his suggestions about the use of the concave mirror very convincing and also his demonstration of Caravaggio’s methods. In the museum you will see that I have something to add to his ideas about Brunelleschi, Velasquez and Vermeer. What he had to say about Flemish, as opposed to Florentine perspective, I found positively illuminating. Perhaps it could only be explained so well by an artist such as Hockney, who uses photo-collage.

Nigel Konstam

February 2008

There is so much I disagree with in the Getty catalogue it will be quicker to name those parts with which I have no argument. There are two students of Rembrandt who though not great are perfectly decent workaday draughtsmen. Their names are Renesse and Hoogstraten. Their style of drawing is not like Rembrandt’s and therefore they have not benefited from the recent handout of drawings that the “experts” have de-attributed from Rembrandt’s portfolio.

I do argue with two others who come into the same category of good, workaday draughtsmen whose work does not in the least resemble Rembrandt’s but have nonetheless benefited from re-attributed Rembrandt drawings. Eekout and Flinck. By what convoluted argument they have been so lucky, the catalogue does not explain.

There is the strange case of Carel Fabritius who was a fine painter but left us no certain drawings. This is not unusual as some painters paint over their preparatory drawings, which were done directly onto the canvas (like Hals and Vermeer). CF has been gifted two very fine and typical Rembrandt drawings, on what grounds we are left to guess. Without comparisons there is nothing to argue about. But he is likely to receive more of the same in future madness.

Johannes Raven, is a comparative newcomer to Rembrandt’s supposed stable of assistants or students. He wrote his name on the back of a drawing, which while not being one of the greatest is almost certainly by Rembrandt. (Rembrandt did many careful drawings in preparation for his etchings, they have all been re-attributed. This looks like one of those.) Had Raven written his name on the front we could agree that he was at least claiming it as his work. However, by signing on the back, I would guess he was only claiming ownership. Surely we all write our names in books for that purpose. Luck was on Raven’s side, the “experts” have overlooked that possibility. A whole raft of life drawings by Rembrandt (mostly of his mistress Hendrijke Stoffels), are now re-attributed to Raven!

Most outrageous of all is the case of Ferdinand Bol whose work as a draughtsman scores a lot lower than the category of decent, workaday. Bol has benefited from a large number of really good or great drawings by Rembrandt. Rembrandt once gave him such a magnificent demonstration of draughtsmanship relating to his, Bol’s, painting of Hagar and the Angel. If, with eyes tight shut, we attribute that drawing to Bol there is no reason why he should not have done other great Rembrandt drawings. With eyes open this mirage vanishes. But the fact remains that at this moment Bol appears great, due to gross misjudgements. With little merit, he has had greatness, thrust upon him!

Those, like Bol, that have benefited from the handout, very much diminish Rembrandt’s stature and obscure his unique contribution to the art of drawing. We now see Rembrandt surrounded by a team of gifted mediocrities, who have made quantum leaps on occasion and who will in due course inherit more of Rembrandt’s greatness, unless, of course, we can unseat the present regime. The uncanny feebleness of modern scholars can only be the result of promoting the most loyal and unquestioning students over several generations of scholarship. They don’t seem to possess eyes or minds of there own. They religiously follow the now untenable theories of their teachers.

Benesch told us that Rembrandt’s “inner vision (of the Biblical subjects) was as if he had seen them in reality”. My experiments demonstrate that he “produced” them in reality by the use of models and that is part of the reason why they are so much more convincing than other artists’ inventions. Unfortunately, for generations we have been fed the idea that what is imagined is superior to what is observed. (Rembrandt himself would have laughed at such a notion.) It is therefore, difficult to persuade today’s art students that they should follow Rembrandt’s example and feed their imagination on reality. Thus, the mythology of Art History has undermined a well tried road to improvement. The “imagination” mythology is yet more dangerous because it diverts our attention from the real world in which we live. Without attention we will falter.

CONCLUSION I hope with these four critiques aimed at the most recent example of Rembrandt scholarship I have conveyed the urgent need for change.

The evidence I have put before you was all there in my Burlington article of February 1977, I have simply amplified it to the point where one can claim that there is no possible room for further doubt. Rembrandt did use large groups of live models, dressed in his extensive theatrical wardrobe, as in the “Adoration of the Shepherds”(see film on YouTube where it is possible to compare the paintings with the photos of the maquettes) on many occasions. An unbiased eye could have deduced the same from a fairly casual perusal of his collected drawings. The mirrors were a proof, which has still not been acknowledged. It needed a desparately biased collective eye to deny the obvious. Many thousands of students have had the wool pulled over their eyes since 1977. This must stop!

Rembrandt is universally regarded as among the great seers of humanity:

a creative genius. It is worth inquiring how he achieved this

pre-eminence. Unlike his chosen artistic partner Lievens, he was not a

child prodigy. In fact, his early works give no inkling of the genius he

was to become. It is not easy to decide who was the major influence on

his development Lievens or Lastman. Lastman was the master in whose

atelier Rembrandt and Lievens met as students.

I tend to favour Lievens; as Rembrandt’s very short stay with Lastman (6

months) suggests antagonism of some kind. Rembrandt made numerous copies

of Lastman’s work. Perhaps these copies were a compulsory but resented

part of the Lastman teaching. Rembrandt’s copies of Lastman are also

criticisms. On the other hand he learnt rapidly and uncritically from

Lievens. His early Leyden works are very strongly influenced by Lievens.

Rembrandt and Lievens worked together from nature, perhaps this was the

crucial difference between the methods of teaching and speed of

assimilation. If this is so Rembrandt had learnt the prime lesson of the

great leap forward in science. Observing nature directly was the secret

of that success. Furthermore, the documents of Rembrandt’s life give

incontrovertible support to the idea that working from nature was

crucial “anything else was worthless in his eyes”. It is difficult to

see how scholarship came to the opposite conclusion: that Rembrandt

imagined his Biblical pieces. Even today scholars remain convinced of

that idea. Perhaps I should attempt to explain their strange behaviour.

[There are two aspects of recent scholarship that are entirely

undermined by my re-discoveries:

1. the dating of drawings by style is no longer tenable. The changes

in style are demonstrated to be the result of either different

media or different stimuli: reality, reflection or imagined.

2. the vast literature on the iconography of Rembrandt and his school

becomes a laughing-stock. All that speculation about the shifts in

emphasis found in the student works are explained by the differing

view point of the physical groups of models in Rembrandt's studio.

These are not mere peccadilloes that can be lightly laughed off. The

scholars are used to being taken seriously, they are entrusted with our

artistic patrimony. These two major gaffs undermine their status as

experts.]

**************************

An unusual characteristic of Rembrandt’s behaviour is his acceptance of

failure as the possible outcome of an experiment. He did not tidy away

his failures as others did. If you accept the greater, more prolific

Rembrandt that I propose, it could be said, he advertised his failure to

draw from the imagination. I interpret this “carelessness” as a

wonderful openness and generosity. He seemed to want us to know how he

had arrived at the summit; perhaps, he did this so that we could emulate

his behaviour and push further with his insights into the working of the

psyche in the physical world.

Rembrandt earned a reputation for leaving his work unfinished but was

unconcerned. Furthermore, only about twenty drawings can be identified

by signature or handwriting, the rest we have to chose according to our

understanding of his aims and style of thought. Rembrandt’s confidence

in his own unique character as an artist was justified. The sensibility

of our “experts” is the issue. For instance ex. 7 & 8 are both typical

of Rembrandt’s concerns and his habits as an artist. The little dog in

Ex.9 is a veritable Rembrandt trademark! He loved dogs and could

obviously draw them from memory, unlike his angels.

Example 7

No.7 has been re-attributed to Drost, in spite of the fact that

Rembrandt did an etching of precisely this subject. The treatment of the

clasped hands of Tobias could hardly be closer to the hands of his

mother in the drawing still accepted as a Rembrandt; reproduced in the

catalog opposite for contrast. The angel has that clumsy feel of

Rembrandt constructing from imagination rather than observing. All the

other figures express shock as we would expect from Rembrandt.

Example 8

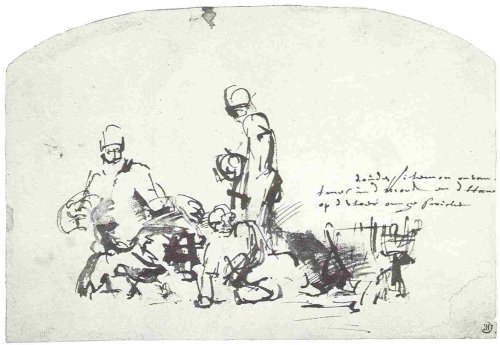

Ex.8 is re-attributed to an unidentified student of Rembrandt. We are

therefore unable to compare with known examples. We can be certain that

the central group would be much closer to the Rembrandt on the opposite

page. In fact, the “mocker” is so typical of Rembrandt and better

realized here, than in the accepted drawing. If I was going to talk of

the style of this figure I would be referring to it’s compactness, its

sculptural quality, it’s balance, it’s geometry and it’s expressive

quality. The handwriting is of no importance to it’s quality as art. If

we talk about the style of Dickens we are looking at his entire

philosophy, his use of words, not his handwriting! Why can we not get

Scotland Yard onto these drawings to compare inks, pens etc. they would

make a far better job. Our experts are to be pitied, not to be listened to.

Fortunately, Rembrandt signed and dated his etching plates. Therefore

the etchings and paintings give us a fairly reliable foundation on which

to build. They give me the feeling of a man so absorbed in his journey

that he will sacrifice whatever is necessary in craftsmanship,

draughtsmanship or detail to keep up the momentum. “A picture is

finished when the painter feels he has expressed his intention in

it.”(Rembrandt as reported by Houbraken). What an excellent example for

us all: this is why his intentions are so obvious to some of us. His

drawings should be seen as steps towards finding his intention: that is

his interpretation of the Bible story. Ex.1.expresses a particular

relationship between Lot and the Angel, this is Rembrandt at work with

his practical brand of imagination: sodomy is a male concern, forget the

pillar of salt.

There are many important lessons we can learn from Rembrandt:-

One, is not to be frightened of failure, we need to learn to acknowledge

our failures and then learn from them.

A second lesson is to learn to feed one’s imagination. Rembrandt did

this by producing model groups in his studio; the closest he could get

to the actual occurrence (the Bible story). This was a part of his art.

His unique success in depicting human relationships lies in the physical

“production” of the re-enactment. “He would spend a day or even two

adjusting the folds of a turban until he was satisfied”. We can presume

that he spent equal time arranging his actors.

Third, was his drawing strategy: he put top priority on the disposition

of the masses in space. This is how the physical pose expresses the

spirit of his protagonists so brilliantly. Perhaps, this can be

appreciated more fully by those who practice drawing or acting

themselves. The scholars’ study of style amounts to no more than the

study of the idiosyncrasies of his handwriting, which they have then

misinterpreted and over played.

The scholars’ search for “ the leaner, fitter Rembrandt” has pruned away

most of these valuable lessons for artists. We must learn to see

Rembrandt’s drawings as he himself saw them: as journeys of discovery,

which only occasionally end with the hoped for, pot of gold.

Surprisingly, Rembrandt did not sign the jewels, he signed his gifts in

autograph albums etc. which were often from imagination

Example 9 Homer

and therefore mediocre. He unwisely left it to the taste of the connoisseurs

to recognise his true hand. He even left proof of authorship on his

least satisfactory products.

Ex.10, B.960 Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis, an illuminating inability. Rembrandt has had to write the story that the drawing fails to tell.

The museum“experts” tend to see the drawings as valuable items in a

collection, and their job as to weed out the duds. I hope I have shown

sufficient reason why we do not want that weeding to continue; we lose

much too much in the process. Tragically today’s scholars are not good

at weeding. Through their pruning over the last 100 years we have lost

sight of many of Rembrandt’s greatest drawings . Their confidence swells

as the great Rembrandt shrinks; they must be stopped!