I have given 3 tours of the Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum to demonstrate the evidence that the most often praised and photographed of the sculptures are not Greek but Roman replacements for the originals probably done 570 years later. Richard Payne Knight, a connoisseur and MP, had the same idea at the time Lord Elgin was selling his collection. He was disgraced for his presumption but I have concrete evidence that he was right. My evidence is easily appreciated by the untrained layman because the Greek work is discoloured by smoke from a chimney I discovered and published in The Oxford Journal of Archaeology in 2002. I am to contribute to a Plaster Conference on the 6th & 7th of April 2020 that has been described as “having the potential to revolutionise the entire field of Greek and Roman sculpture”. Here is the script of the tours. The quotes from Roger Fry and Keneth Clark are important to understand just how far modern criticism has strayed from the preferences of Rembrandt, who owned 30 Roman portraits and filled 2 books with studies of them. A revolution in art is well over due.

A Tour of the Elgin Marbles

Good morning, I am Nigel Konstam, a sculptor/bronze caster, not a classical archaeologist so I see these sculptures from a different viewpoint to the archaeologists; with much more practical knowledge of the processes involved and perhaps less mythology in my education. I do not come to these famous icons of art with the same weight of traditional opinion as the archaeologists. Nor am I here to devalue these great works but I do hope to persuade you that the people responsible for the better half of them are not the Classical Greeks, as is generally supposed, but Romans. This is hard to accept for those who know their art history but I expect to convert you all within a few minutes.

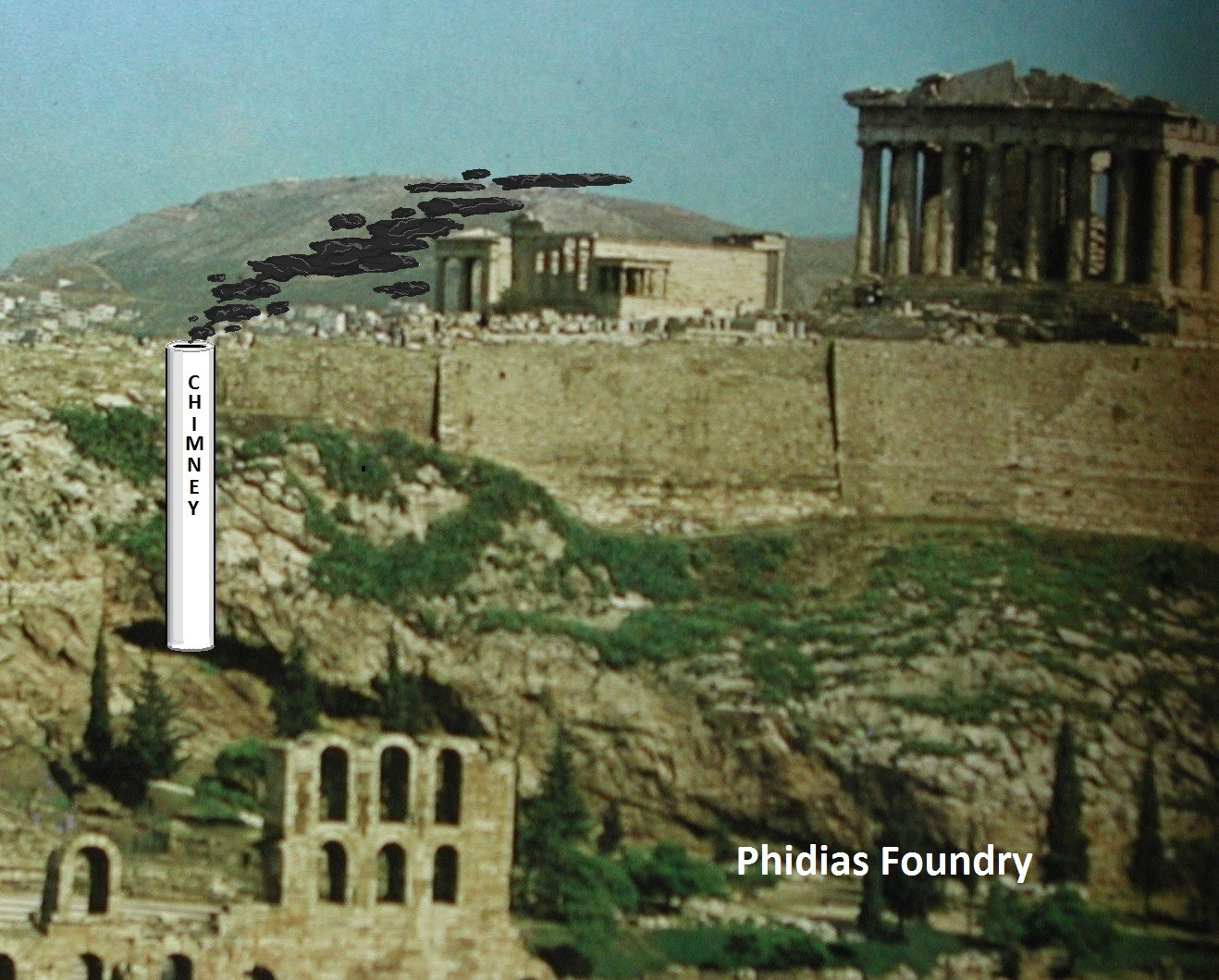

In the year 2000 I was lucky enough to discover an ancient chimney on the Acropolis Rock in Athens used by Phidias, the sculptor in charge of the works on The Parthenon. He used the chimney for melting bronze for his gigantic bronze statues. I have recently come to believe this chimney was responsible for an industrial scale smoke pollution which I hope to demonstrate today was responsible for ruining the west pediment with more than 500 years of acid rain. My dicoveries were published in The Oxford Journal of Archaeology in 2002 and the site in Athens is now signposted as a chimney.

We are here in a gallery full of sculpture from The Parthenon the sculptures were brought to Britain by Lord Elgin and so they have the local name of “The Elgin Marbles”. All were taken off The Parthenon, the most famous Greek Temple built by Pericles in Athens starting in 448 BC. The original sculptures were completed in 432 BC. We are in a perfect place to assess most of the evidence of smoke damage.

We are circulating a page of photographs of the evidence we cannot see today because it is in Athens. It is relevant to my thesis – the thesis being that the whole of the west pediment and “The Horse of Selene” on the east pediment are in fact Roman replacements for the original Greek works which had been ruined by smoke from the Athens chimney. I am not the first to suggest Roman workmanship but I am the first to explain how that came about. The evidence of smoke is very easy to follow, the evidence of style which comes second may be slightly more difficult for those untrained in these matters.

Figure 1 – This shows the relationship of the chimney to The Parthenon. The chimney emerges about 150m down wind from the west facade. The west pediment would therefore have received the full brunt of the weather and smoke driven by the prevailing south-westerly wind. Even now after extensive cleaning and repair there is plenty of evidence that The Parthenon was once blackened by smoke. John Boardman, a well known classical archaeologist was looking for a source of pollution for The Parthenon – I found the chimney and as a result finally came to the upsetting conclusion that many of these works are excellent Roman replacements for the original Classical Greek works.

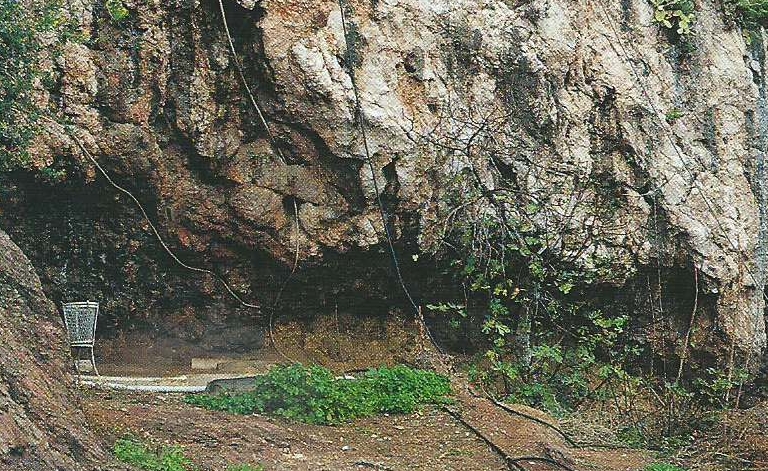

Figure 2 – This shows the upper west end of the diagonal C section cut in the Acropolis rock which I discovered, it is full of soot and tar throughout its length and discoloured orange by heat. Interestingly at the top end of the existing chimney-section the signs of smoke disappear. I therefore hypothesize there was a vertical tower chimney (represented white in fig.1) that would have taken the smoke yet closer to damage The Parthenon. I have no way of knowing how high the chimney was but undoubtedly a metre or two. Furthermore, if one was designing a building to catch smoke The Parthenon would be a good solution with its outer columns and inner wall making a corridor to conduct smoke along its length.

Figure 3 – This shows the passage of smoke through the Parthenon, mainly high up on the walls and ceiling but particularly along the west and south sides of the Parthenon you will still find blackening under the architrave caused by centuries of smoke rising from below.

Figure 4 – This shows an early photograph of the Parthenon before restoration. We see it is heavily blackened particularly at the west end, and less black around the damage caused by the explosion of the Turkish arsenal in 1687. The Acropolis was being bombarded by the Venetians, the Turks kept their gunpowder in The Parthenon. Naturally, tremendous structural damage was done by the explosion but the pollution would have been short lived. The chimney would have been polluting perhaps for 500 years 1,500 years earlier. Bearing in mind that those pillars have been washed by rain for 2000 years before the photo, we can guess the pollution in Hadrian’s time would have been very heavy indeed.

From here, below the east pediment, I ask you to look at the colour/tone difference between The Horse of Selene (on the extreme right) and the rest of the east pediment. I think you will agree with me the horse is much lighter. If you now look at the west pediment it is all the light colour of the horse. I believe that all the lighter work is Roman replacement of the original Greek designs. If we now go over to the east pediment I will explain why.

Here we see two very damaged genuine classical Greek horses to contrast with the perfect clean Roman Horse of Selene. We see blackening in many places on this pediment, under the thigh of Dionysos there is even erosion under his knee, from the acid smoke rising from below. On the stool of the two ladies next to him there is heavy evidence of smoke rising from below and depositing soot on the stool, the skirt and legs. If we go round the back we see very heavy deposits of soot that has survived four cleanings (the one here in the museum in 1938 was scandalously severe, removing up to 2 mm of the surface in some places). The reason for the position of this heavy deposit is that in classical times they were carving marble with iron or bronze tools. The fragile nature of the tools confronted with the hard marble meant that they worked very slowly pecking away at right angles to the surface but this had the effect of bruising the marble beneath. That is the crystalline structure was disturbed creating crevices which allowed the smoke to enter deeply, well beyond the reach of any scouring. Working in this valley between the cloth of the sleeve would have been more difficult and therefore created more bruising and more penetration.

Figure 5 – Horse of Selene (right) compared to the greek original (left)

Figure 6 – Damage caused to sculptures in the Parthenon. One can see on the knee of Dionysos (right) a dent at the top where erosion has taken place; also the parallel ridges on the thigh suggest that a layer of black erosion has been chiselled off (probably before Hadrian’s more thorough restorations were undertaken).

Later carving was done with steel tools at an oblique angle to the surface which did not bruise the marble beneath, hence the dark gray of the original work and the lighter colour of the replacements. I guess that these replacements were paid for by the Roman Emperor Hadrian because he had the power, the taste and the willingness being a great admirer of Greek art. I do not insist it was he but at the time of the purchase of the works from Elgin, an art expert who was also an MP, Richard Payne Knight suggested the works were Roman and of that period. He was disgraced as a result, though I now believe he was right. Elgin himself had left two figures, of King Cecrops and his daughter, on The Parthenon because he believed them to be Roman copies.

The reason why the horse had to be replaced although furthest from the source of smoke is twofold. First because the nose and mouth actually overhang the parapet and therefore received the full effect of the rising smoke; and second because the work on the hollowed mouth and nostrils would have undermined the crystal structure severely thus increasing the entry of smoke and the chances of collapse.

Many regard these sculptures as the most beautiful ever made. It is interesting to reflect that what I now believe to be Roman work has been particularly lauded and reproduced as typical examples of Classical Greek work.

We have looked at the most obvious evidence. Before going on to demonstrate the stylistic difference of the Roman work, which is more subtle.

This horse’s head is crisp and geometric suggesting a Roman hand. Let us return to genuine Greek Dionysos in order to compare him with the Illissos figure on the west pediment, which I believe to be Roman, in the Dionysos the forms are more rounded and with little or no sense of the underlying muscle, fat or bone, where the museum’s own brochure describes the figure of Ilissos on the west pediment as “an admirable example of the mastery with which the surface textures of skin, tense or loose, and the underlying muscle, fat and bones are indicated by the sculptors of the Parthenon. I agree about the excellence but not about the authorship. I have always regarded this figure of Illissos as the greatest of all. I particularly admire the way the stomach stretches between the rib-cage and the pelvis and the differentiation between the two thighs, all brilliantly observed. I have described this work as by an earlier Bernini from ancient Rome. Recent scholarship has consistently taken a dim view of Roman art. Roger Fry in his “Last Lectures” as Slade Professor at Cambridge said of Rome “the one great culture of ancient times of which we can, I think, say that the loss of all her artistic creations would make scarcely any difference to our aesthetic inheritance.” I hope my demonstrations have persuaded you that this assessment, is gravely mistaken. It has had enormous influence.

Finally to bring this new truth up to the present let me quote Lord Clark, he spent a page and a half denigrating Rome’s contribution to art in his “Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance”(1966) with such phrases as “what could have persuaded Rembrandt to have drawn these posturing marble divinities – smooth, soulless and inane”. Clark would doubtless be somewhat embarassed to find out that this magnificent piece was in fact a Roman copy.

Unlike Clark and modern taste generally Rembrandt admired Roman art intensely. He owned 30 Roman portraits and filled two books with drawings of them. The syntax of his drawing is deeply influenced by the Roman tradition. Sadly, this modern attitude has led to many major art schools banishing the cast-room, where traditional drawing was taught because that illusive factor “form” has a direct relationship to Greek or Roman sculpture. As a student in1956 the main aim of an art education was to see form.

When we have finished here I hope to have time to explain why this low estimate of Rome goes hand in hand with the destruction of connoisseurship. I will demonstrate my analysis of the three dimensional geometry in a bust of Hadrian, room 70. This geometry, I believe, became the basis of the better part of European drawing. As prime examples of the use of Roman form I put forward Masaccio, Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas and Giacometti.

There are many of my videos on YouTube. If you wish to check out what you have heard today you can visit my website www.nigelkonstam.com where you will find an ebook entitled “An Alternative History of Art” in which chapter one deals with Greece, chapter two with Rome and chapter nine with Rembrandt and many blogs. All suggest a new start with a new, more accurate history for art. We need to abandon the false traditions of Art History that have gone so far astray.