I have been scathing about the scholars ability to judge quality in art. Let me give two of the twenty examples I might have chosen. Rembrandt made many etchings of nudes, even the best are often marred by passages that are of inferior quality. Arnold Houbraken who was a painter and a contemporary of Rembrandt’s in Amsterdam, also an admirer was also very critical of Rembrandt’s drawing on occasion – “it is very seldom one finds in Rembrandt a well painted hand”– of his female nudes……“he has produces such pitiful things that they are hardly worth mentioning, they are invariably repellent and one can only ask oneself in amazement how a man with such talent and intelligence can be so stubborn in his choice of models.” – . So we have been warned – Rembrandt is not always attractive.

As a student I loved Rembrandt because he did not attempt to hide this variability. It was encouraging to see that even the great Rembrandt could live with passages that I felt I could out-do myself. He started from a ground base that was not all that exceptional, in fact quite ordinary. He was most unusually truthful about this and also about what he perceived.

The Arrow Holder

Look at this etching (The Arrow Holder) that has gone through many adjustments (changes of state), the hand holding the arrow, in fact that whole arm is badly drawn. When we compare it with the arm in the preparatory drawing B1147 we find there an arm that recedes much more satisfactorily.

B1147

We can be absolutely sure that Rembrandt did the etching (he signed it on the plate) all previous scholars have accepted the drawing which although not exactly the same is clearly a preparatory drawing for the etching. (The drawing of the light on her back is identical given that one is done with a pen, the etching with a needle.) But Mr.Royalton Kisch, recently of the British Museum, has the arrogance to reject it. In spite of Houbraken’s warning he finds the drawing “frankly indifferent”. I don’t disagree but I don’t find that reason for saying it is not by Rembrandt.

You may ask does it matter? – yes it very much matters because the style of this has been the reason for Kisch and his friends to relieving Rembrandt of many more drawings. This is one of many preparatory drawings that have been recently rejected. The “experts” should read the early documents every day till they change their attitude. They have no conception of how they have trampled on holy ground.

The second example is much the same, only in this case the etching is all very poor in relation to the preparatory drawing which is a beauty and has been rejected by today’s “experts”.

|

Preparatory Drawing |

Etching of young man leaning |

Look at the pose of the head, in the drawing a bony young man is seen leaning back on the wall behind (protected by a drape we see in the etching). The foreshortened features are beautifully seen but Rembrandt has lost it in the etching. The long bony face has become squashed (compare where the tip of the nose is in the drawing, it covers one eye, not so in the etching) Even allowing for the fact that Rembrandt has apparently moved further back for the etching, the youth’s lower legs seem very stumpy there, compared with the pose in the excellently descriptive drawing.

These new findings were all published in the catalogue for an exhibition held in The Rembrandthuis Museum in 1984-85. (They will doubtless be repeated at the forthcoming Getty exhibition) Has any art historian raised his voice against them? Not as far as I have heard. The sad truth is that art historians are not very good at judging quality. There must be 10,000 trained artists out there who can see what I am talking about. LET US HEAR FROM YOU (in the comments section). It is surely part of an artist’s duty to help preserve the visual culture, which is now in terminal decay.

This blog makes a case for starting again with the neglected art of observation, particularly the art of observing human nature. Humanism: how the spirit of Man expresses itself in the physical world. Humanity is the most interesting subject because it concerns us most deeply. It was the prime subject of art for the 40,000 years prior to this passed century. The subject never pales because life moves on and art changes with it.

Unfortunately the writers on art are somewhat outclassed by the artists themselves when it comes to observing. Some artists have spent their lives studying it. The critics protect their self esteem by avoiding this subject matter and concentrating on abstract ideas, where they feel safer.

After 100 years of this bias in public notice it is little wonder that observed art, the art that Everyman can understand, is in steep decline. Through habit we try to take seriously establishment art (Art Bollocks as it is so justly dubbed by the Jackdaw Magazine) but the effort is seldom worth making. Their art is only of interest to the few who are making money out of it. Art matters because seeing and responding to the world about us is essential to our very survival and art is our best educator in this.

Rembrandt scholarship is used as a demonstration of how far the rot has gone. The scholars seem completely out of touch with human feeling. Having spent their lives in company with the greatest artist to observe humanity, they have so undermined his reputation that students can no longer trust him. Observing the results, they must represent the steepest artistic decline in human history. It is no coincidence that the decline dates from the rise of Art History as a political power. Artists have been too lazy or naïve to direct their own evolution. They have left it to the likes of Serota at the Tate and the Rembrandt scholars.

It is going to be very difficult to stop them but that is what must happen. The Jackdaw and the Stuckists have unearthed sufficient evidence to put many of them “away”. This is well worth considering as a tactic. I have shown that the Rembrandt scholars are simply protecting themselves, their tactics of head-in-sand have worked but done immense damage to the cause of art as a result.

In a nut-shell – my article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” published in the Burlington Magazine (Feb.1977) demonstrated that the hypothetical development of Rembrandt’s style created by generations of Rembrandt scholars, was no longer tenable. The variations in style were due to Rembrandt’s responses to the very different stimuli of reality or the reflection of that reality in a dim polished metal reflector (glass of the necessary size did not exist in Rembrandt’s day). Below I show three illustrations from that article to clarify this point. Many more examples are available (link to www.saveRembrandt.co.uk)

Take this link to see a 5 minute film which shows the same use of mirrors with two of Rembrandt’s paintings: “The Adoration of the Shepherds” in London and in Munich. The London one (observed in a mirror) has been discredited by the “experts” of the Rembrandt Research Project though it passed all tests that The National Gallery put it through. It probably now resides in the basement there.

The briefest perusal of the three catalogues put out by the three main collections of his drawings (The British Museum, The Rijksmuseum and the Boymans of Rotterdam) show that the “experts” are still spending all their time pretending to put dates on drawing according to style – making no attempt whatever to look at the human aspect which was Rembrandt’s chief concern. Their lack of aesthetic discernment pales into insignificance beside their lack of ordinary common sense. Either the authors are too dim for the job we entrust them with, or they badly need psychological help. The same applies to the regiments of Rembrandt scholars elsewhere.

ARE THE NEW FACTS ABOUT REMBRANDT EVER DISCUSSED? IF SO

HOW ARE THEY COUNTERED? WE WOULD LIKE TO HEAR..

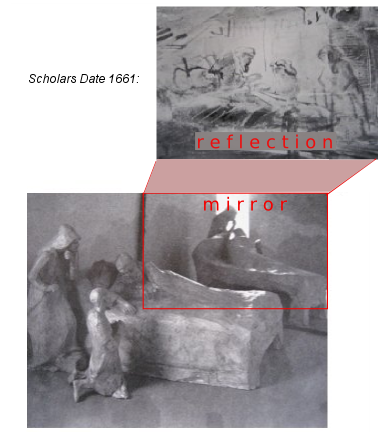

The photo is of a maquette to represent Rembrandt's studio set up with live models and a mirror for his series of drawings of Isaac and Jacob. Below is a drawing that scholars have dated 1652 ( Rembrandt's classical style) and above a drawing they date 1661 (his mature style). The photo demonstrates how both were drawn from the same seat in the studio, under identical lighting conditions and very nearly the same group of models, only Rebeccah has moved. Common sense suggests they were drawn one after the other- not after a gap of 9 years. Clearly the style of the two drawings is very different but the difference can be very well explained by Rembrandt's differing response to reality (below) and reflection in a dim mirror (above). This same difference has been demonstrated many times in Rembrandt's work. eg. The Adoration of the Shepherds, The Dismissal of Hagar and this series of drawings of death bed scenes. Konstam's article “Rembrandt's Use of Models and Mirrors” was published in The Burlington Magazine in February 1977. That article invalidated stylistic criticism but the scholars continue to destroy Rembrandt and waste everybody's time with their out-dated theories.  Scholars date 1652 |

|

|

To pursue Bols good fortune we need only turn to the Rijksmuseum catalogue p.134, there we find that a particularly fine Rembrandt drawing has been re-attributed to Ferdinand Bol, a painter of little standing or quality. Bol happened to make a painting of the group Rembrandt set up in his studio of Hagar and the Angel. Even better luck he was working near Rembandt (just to the left of Rembrandt himself). It is quite probable that Rembrandt made the drawing to help Bol get a little more excitement into Hagar’s gesture. If so Rembrandt sadly failed to make his point. Bols Hagar remains unmoved by the miraculous apparition.

In Rembrandt’s drawing Hagar’s hands are a miracle of virtuosity. It would seem that the pen never left the paper as it outlined the the fingers on a most amazingly beautiful pair of hands. Rembrandt quite often drew hands this way but never before so successfully. This was Rembrandt on top form, so is the body of Hagar, gorgeous. The Angel is also typical but not quite so sparkling. The outstretched hand absolutely typical Rembrandt. Our team of three have used this example to plunder Rembrandt’s quality portfolio in favour of Bol on many occasions. Just turn to page 136 and see how a particularly amusing Rembrandt has also fallen to Bols credit. (Vertumnus and Pomona, once exhibited as particularly typical of Rembrandt.)

I know the gang have found comfortable niches for themselves in museums but given they have devolved so far from normal human feelings maybe they would be happier in a zoo.

Bol's dull Hagar

Rembrandt's failed lesson to Bol

B1121 |

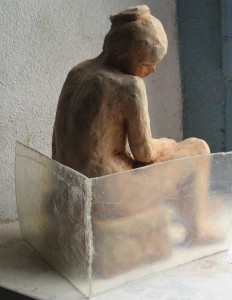

B1121 maquette with space envelope |

My favourite of all Rembrandt’s life drawings can be analysed in a sculptural way. B1121 is one of several drawings Rembrandt made of Hendrijke in his search for a pose for the Bathsheba in the Louvre. Her stool parallels the two sides of the block from which she could be carved. (Rembrandt seems to have had a natural feeling for sculpture though there is no evidence that he ever made any.) The light illuminates the side plane and strikes across her back defining the forms exquisitely. This is no idealized goddess but a beloved mistress seen as she truly was: no longer in the first bloom of youth. Not the rounded stereotype of the Renaissance but there, to the very life so that I have been able to make a little sculpted maquette of her. Her knee is seen with just that extra squareness about it that Sickert described as typical of Rembrandt (in his appreciation of The Polish Rider). The squareness serves to define the parallel between the top of the knee and the back plane of the space envelope. Degas often uses the same kind of device.

Every mark Rembrandt makes is defining form in space. I made a copy of this drawing during my first year at Camberwell. I hope that lesson will stay with me always. It was a defining moment.

On the other hand the gang of three (from The British Museum, The Rijksmusem and The Boymans in Rotterdam) who met regularly to coordinate their “findings” take a very different view. Mr. Schatborn, (Rijksmuseum) warns “only very few (of Rembrandt’s life drawings) can be assumed with any certainty to have been done by the artist himself”. Mr.Giltaij (Rotterdam) finds the stove in this drawing “incoherent…while the modelling of the back gives the impression of being over detailed and cautious…the contours (of the figure) are weak and hesitant” these appalling misjudgments fly in the face of all previous scholarship, not just mine! I wonder have they ever come across Kandinski’s maxim? – line becomes plane.

B1122

This drawing is usually paired with another of Hendrijke in the same pose (B1122) because as Schatborn admits “at first sight the two drawing resemble one another very closely… the nearly identical position of the two figures on the surface of the page – the use of the same ink, the lines that do not describe with precision and touches of transparent water colour”. The two drawings are indeed so identical in feeling, in materials and treatment that it is impossible for any one but an “expert”to doubt that Rembrandt did them both, probably in the same sitting. None the less, the greater of the two (B1121) is now attributed to Aert de Gelder and the lesser is still a Rembrandt. I say lesser because the front plane of her chest is very mildly out of geometry with the side plane. One can see that Hendrijke has slumped forward a little while posing because of the repositioning of her left shoulder. Her left breast was also repositioned but not sufficiently. Otherwise Rembrandt’s sense of form and structure are of the same very high, one could say, canonical order, in both. Is it at all likely that Rembrandt would have invited young Aert in to share this intimate drawing session with his mistress? In the Getty catalogue other students are credited with drawings of Hendrijke.

What can one say, the temerity of the gang knocks the breath out of me. How is it possible to teach drawing in a culture that can tolerate such minds in the top echelons of Rembrandt studies? I saw these two drawings hanging together in the Rijksmuseum exhibition, “Rembrandt and his Workshop”. I nearly had a fit.There was no workshop. It is a modern fabrication to explain away the many painting the RRP have de-attributed. Rembrandt had a good, expensive, school of painting. He was not that great at teaching drawing judging by results. His students are nothing like the master, few are even tolerable draughtsmen but there are hundreds of Rembrandt drawings re-attributed by the “experts” in the recent past to his dull students! Ferdinand Bol has been particularly fortunate in this respect.)

I have said quite a lot about the mistreatment of Rembrandt’s life drawings in my website

www.saveRembrandt.org.uk (save him from the experts, of course.) (For more about Woman seated on a stool take this link) I shall probably say a good bit more here. Please if there is anyone left out there who understands what I am talking about, help me in this crusade. I issued three news sheets at the time of the “Rembrandt and his Workshop” exhibitions (1991). I put on a show in St Martin’s in the Fields for the day of the opening in Trafalgar Square, it was very well received by the hundreds who saw it but for all my efforts the establishment marches on unflinching.

Art matters.

We need to demonstrate in the street, if necessary to stop the rot. Wilfred Owen wrote-

“Reach at that arrogance that deserves thy harm,

And beat it down before its sins grow worse!”

Look around you and see the results on the younger generation who no longer look to Rembrandt for guidance; they can no longer trust him. The gang have no idea of the harm they have done. They are victims of a truly terrible training. The whole apparatus of Rembrandt scholarship must be stopped; and only restarted with an entirely new set of criteria. One of which might be a minimum of three years at a good art school before taking up art history!

I would be pleased to hear from anyone from Harvard where I said diplomatically (in 1978) what I say here, more stridently.

Good friends have suggest I should be more moderate, more reasonable in my approach to the “experts”. In 1977 I was most reasonable, 35 years later I feel it is reasonable to follow Green Peace’s excellent example – be reasonable when you have people to reason with.

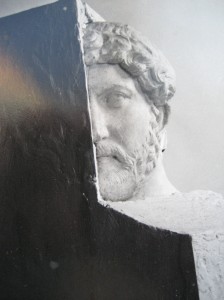

Hadrian with his nose in the corner of the block |

I have made an analysis of a Head of Hadrian, first published in Apollo Magazine (1978) and summarized in my book on sculpture ( Sculpture, the Art and the Practice isbn 0-9523568-1-3). Essentially it shows how the survey geometry used by the Romans to copy in stone, has had a great and lasting effect on European art; at least as great as the legacy of ancient Greek sculpture. It was after all much more widely distributed and admired through out Europe. Prior to the arrival of the Elgin marbles in London, Greek sculpture was known in Rome a little and hardly anywhere else.

I use Holbein as the greatest exemplar of the alternative tradition before Rembrandt. ( I can rekindle a sculpted head from any one of Holbein’s drawings, they are so brilliantly descriptive of the three dimensional world.) Rembrandt made a beautiful copy of a Holbein, which in terms of geometry is considerably better than the original, look at the volume of the head and the general pose. Alas it is not included in any of the catalogues known to me, though it is catalogued as a Rembrandt in Oslo, its home. Fortunately, I have a photocopy.

Virtually all of Rembrandt’s observed works show some sign of this geometry. For works he constructed from “imagination” he was forced back onto the Greek/Renaissance tradition but he seemed to make a point of guying it when he did so.“Rembrandt was taught by nature and by no other law.”

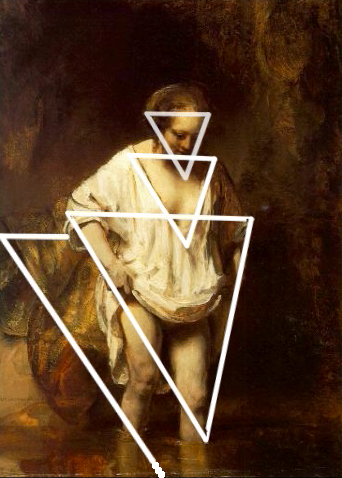

Woman Wading with geometry |

His “Wading Hendrijke” in The National Gallery, London is a magnificent oil sketch held together by a series of isosceles triangles laid parallel in space with the triangle that defines the neck-line of her shift. Rembrandt widened the geometry of Holbein to include space as well as solid. I call the space around Hendrijke – a space envelope. Another way of looking at the space envelope is to see it as the shape of stone a sculptor would use to carve the figure. In this case if we start from a block – by putting her head into the corner (like Hadrian’s nose) we can save half the block by sawing it in half, along the diagonal. Both pieces would make a space envelope for Hendrijke. (This concept is further explained in my sculpture book).

Space envelope for Wading Woman |

Rembrandt's drawing B395 with geometric diagram |

Rembrandt’s geometry is broader than Holbein’s, more implied than stated. An artist learns his syntax as we all learn our verbal syntax, by usage. I hope Rembrandt would understand what I am talking about but I am not certain that he would. If it helps us appreciate his work that is all that matters to me.

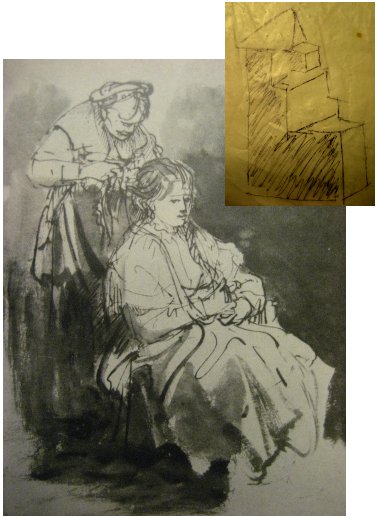

Looking at this charming drawing of a girl having her hair plaited, though the handwriting is very fluid the geometry is firm. If we examine her head we see that Rembrandt has drawn in the top of the block from which he carves the head. Two thin lines at the top of her forehead are the orthogonal between front and top planes. The hair on top establishes the top plain, her features define the the axis of the front face. We can then follow the plait in it’s form defining journey across her shoulder down to her breast and down to where it is caught between finger and thumb (all gorgeous drawing). |

| The hands are seen as simple shapes and directions, perfectly articulated. Her lap is described with apparent casualness but the scrawling pen line shows us the plane and roundness of the thighs beneath her skirt. The vertical of the skirt falling to the floor completes the step-like structure of the drawing.

The hairdresser has not got quite this volumetric sureness. The axes of her head are clearly defined. Her head forms the apex of a pyramid that is completed by her forearms at the base. Rembrandt’s shorthand is made readable because it is so firmly underpinned with geometry. |

|

There is one more painting and hundreds more drawings by Rembrandt around in the world than those acknowledged by the experts. They are probably in museums or private collections but may be in the hands of dealers.

On Youtube you can see Konstam’s model reconstruction of the scene in a barn which Rembrandt observed direct from his group of real people to create his painting now in Munich. The camera then pans round to a reflection of that complex model group seen in a mirror of polished pewter (polished copper would have produced a yet more Rembrandtesque warmth of colour). The reflection shows the subject matter of “The Adoration of the Shepherds” now probably in the basement of The National Gallery (London). It was always accepted as a Rembrandt until the Rembrandt Research Project pronounced that it could not possibly be by the same painter as the Munich Rembrandt.

Amusingly only two objects have to be repositioned; the cow and a little boy with a dog. The adults and a central post in the barn with a basket hanging from it remain as they were, even the spaces between them remain constant.

The complexity of the array and the accuracy of its reflection must prove (beyond reasonable doubt) that Konstam’s long scorned version of Rembrandt’s varied output has triumphed over the establishment version that has tried to impose a level of consistency, which is completely at variance with the recorded character of the artist.

Konstam now comes forward with two long forgotten preparatory drawings for the two paintings which he reasonably claims are therefore by Rembrandt, for certain. The first was published as a Rembrandt by W.R.Valentiner in his 1934 catalogue. The second was recognised as a Rembrandt by H de Groot in 1904 but written off by S.Slive in his Dover publication 1965.

Published as a Rembrandt by W.R.Valentiner in his 1934 catalogue

Recognised as a Rembrandt by H de Groot in 1904 but written off by S.Slive in his Dover publication 1965

Konstam points to a particularly beautiful drawn young woman in the drawing wearing a broad brimmed hat and carrying a lantern. The young woman appears again in the National Gallery painting but her hat and lantern are carried by the tall bearded man behind her. This is Konstam’s version of Rembrandt, using live models and mirrors, swapping hats etc.

Beautifully drawn woman with hat and lantern |

The woman's hat and lantern are carried by the tall bearded man behind her in the National Gallery Adoration |

Over several generations the “experts” have constructed a castle in the air which has finally collapsed because its founded on a series of fallacies. Ninety percent of their judgements from 1904 onwards should be put straight in the waste paper basket. The present scholars should be relegated to pronounce on Warhol and the like. They are fit for nothing else because they are blinkered by their training. It is a sad fact that we see only what we expect to see, in the main.

Two quotes from the Phenomenon of Man, (P.Teilhard de Chardin) “Seeing. We might say that the whole of life lies in that verb.”p.31 “a truth once seen, even by a single mind, always ends up by imposing itself on the totality of human consciousness.” p.218

So why is it so difficult to transmit such a truth? I have been at it half a life-time (since 1974 to be precise) and still have not got it through. Thank God for internet, it may give me half a chance. The answer to my question is - because many others think it is their territory and I, a mere sculptor, should not trespass. There is the other complication that what I have seen makes them (the many) look rather foolish for not having seen that truth for themselves. Furthermore that blindness goes back several generations.

I will be aiming at three individuals who made up a team of “experts” in charge of the main collections of Rembrandt’s drawings at The British museum, The Rijksmuseum and the Boymans in Rotterdam. They have produced three new catalogues of their collections which follow the fashion set by The Rembrandt Reseach Project (RRP) of reducing that great master’s corpus by de-attribution, to a mere shadow of it’s former self. The master’s reputation has naturally followed.

I am in the process of writing a commentary on all the drawings I believe to be by Rembrandt and a few which the “many” favour but I do not. I expect the number of Rembrandts in my commentary to be at least twice as large as a catalogue any of these three might be writing (God forbid).

The emphasis in my commentary will be on Humanism and what Fry called “significant form” a term which was the rage while Fry was around but now out of fashion. I call it “visual syntax” by analogy with literary criticism. Today’s “experts” seem hardly aware of syntax yet no real understanding of Rembrandt’s drawings is possible without it. He has a syntax all his own which I will be at pains to make clear in these pages. Very fortunately computer technology has made possible an explanation that was not available to Fry. Some may well still be guessing what he was on about.

The team of Rembrandt experts I am sure are all very cultured in the sense of being well read, knowledgeable about music, poetry and above all about the literature produced by their fellow art historians. But of what we can term visual culture, that is the culture of artists, I do not detect a smattering, scarcely a vestige. No doubt all have been through the Art Historical mill at smart universities and most probably come out near the top of their year because they have thoroughly adsorbed what their professors had to offer, and there lies the trouble. They come through the mill blinkered by the accumulated prejudices of their predecessors. Unable to see for themselves, they chew over and add to the accumulation of half truths. Rembrandt studies are a vicious spiral that has been spiraling downwards for over 100 years. It must be stopped.

No new knowledge is allowed to enter this closed circuit. This particular artist has been banging at their door for half a life-time and has been roundly snubbed and occasionally robbed of his insights. What I have discovered about Rembrandt’s practice would become established fact immediately in scientific circles because of the weight of evidence (see www.saveRembrandt.org.uk). Yet it has hardly penetrated the mentality of Art History beyond the above mentioned thefts. My evidence has been most unsatisfactorily rebutted in The British Museum catalog. Unsatisfactory because there is no mention of the fact that Rembrandt’s use of mirrors has been noted in nearly 100 cases, which statistically must make it a dead cert.

Furthermore, Max Wykes-Joyce wrote of my exhibition at Imperial College (The International Herald Tribune 27.1.76 ) …with the use of maquettes, photographs, mirrors and a text, illustrates what Konstam believes to have been the working methods of Rembrandt, Poussin and others, and which by implication, contradict much of 20th century criticism and scholarship. Certainly as a working artist the case he makes for the re-dating and reconsideration of many of Rembrandt’s drawings is strong.” And later…”certainly the exhibition is a seminal one that should not be lightly dismissed.” The Observer headlined a quarter page article “The Rembrandt Revelation”. Two very eminent art historians (Gombrich and Montagu) assisted me in writing the text that was published in The Burlington (Feb ‘77). The editor (B. Nicholson) wrote in his letter of thanks “ I find the evidence you have accumulated of the greatest possible interest, and so I am sure will Rembrandt scholars, who must now get down to revising the corpus of drawings!” A similar text was published in Dutch (Rembrandthuiskroniek 1978.1) And yet I believe since this auspicious beginning the whole idea has been brushed under the carpet without discussion.

I WOULD BE VERY GLAD TO HEAR FROM ANYONE WHO HAS STUDIED REMBRANDT AT UNIVERSITY LEVEL, WHETHER THIS IS SO.