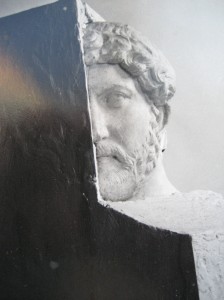

Hadrian with his nose in the corner of the block |

I have made an analysis of a Head of Hadrian, first published in Apollo Magazine (1978) and summarized in my book on sculpture ( Sculpture, the Art and the Practice isbn 0-9523568-1-3). Essentially it shows how the survey geometry used by the Romans to copy in stone, has had a great and lasting effect on European art; at least as great as the legacy of ancient Greek sculpture. It was after all much more widely distributed and admired through out Europe. Prior to the arrival of the Elgin marbles in London, Greek sculpture was known in Rome a little and hardly anywhere else.

I use Holbein as the greatest exemplar of the alternative tradition before Rembrandt. ( I can rekindle a sculpted head from any one of Holbein’s drawings, they are so brilliantly descriptive of the three dimensional world.) Rembrandt made a beautiful copy of a Holbein, which in terms of geometry is considerably better than the original, look at the volume of the head and the general pose. Alas it is not included in any of the catalogues known to me, though it is catalogued as a Rembrandt in Oslo, its home. Fortunately, I have a photocopy.

Virtually all of Rembrandt’s observed works show some sign of this geometry. For works he constructed from “imagination” he was forced back onto the Greek/Renaissance tradition but he seemed to make a point of guying it when he did so.“Rembrandt was taught by nature and by no other law.”

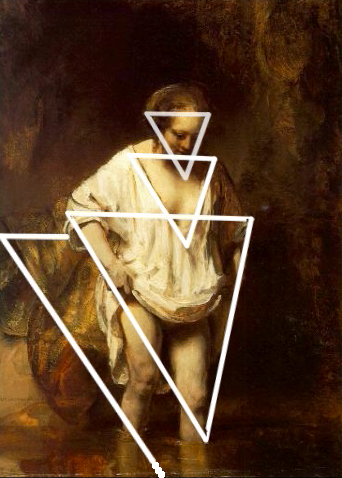

Woman Wading with geometry |

His “Wading Hendrijke” in The National Gallery, London is a magnificent oil sketch held together by a series of isosceles triangles laid parallel in space with the triangle that defines the neck-line of her shift. Rembrandt widened the geometry of Holbein to include space as well as solid. I call the space around Hendrijke – a space envelope. Another way of looking at the space envelope is to see it as the shape of stone a sculptor would use to carve the figure. In this case if we start from a block – by putting her head into the corner (like Hadrian’s nose) we can save half the block by sawing it in half, along the diagonal. Both pieces would make a space envelope for Hendrijke. (This concept is further explained in my sculpture book).

Space envelope for Wading Woman |

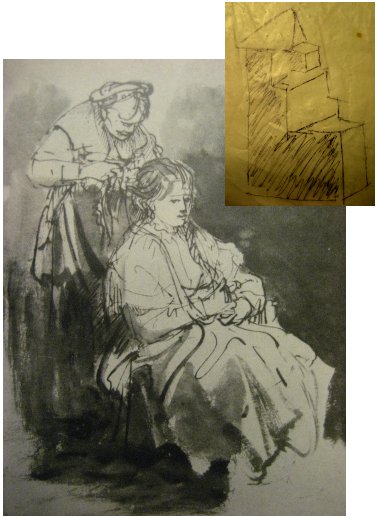

Rembrandt's drawing B395 with geometric diagram |

Rembrandt’s geometry is broader than Holbein’s, more implied than stated. An artist learns his syntax as we all learn our verbal syntax, by usage. I hope Rembrandt would understand what I am talking about but I am not certain that he would. If it helps us appreciate his work that is all that matters to me.

Looking at this charming drawing of a girl having her hair plaited, though the handwriting is very fluid the geometry is firm. If we examine her head we see that Rembrandt has drawn in the top of the block from which he carves the head. Two thin lines at the top of her forehead are the orthogonal between front and top planes. The hair on top establishes the top plain, her features define the the axis of the front face. We can then follow the plait in it’s form defining journey across her shoulder down to her breast and down to where it is caught between finger and thumb (all gorgeous drawing). |

| The hands are seen as simple shapes and directions, perfectly articulated. Her lap is described with apparent casualness but the scrawling pen line shows us the plane and roundness of the thighs beneath her skirt. The vertical of the skirt falling to the floor completes the step-like structure of the drawing.

The hairdresser has not got quite this volumetric sureness. The axes of her head are clearly defined. Her head forms the apex of a pyramid that is completed by her forearms at the base. Rembrandt’s shorthand is made readable because it is so firmly underpinned with geometry. |

|