Casole has just become a major art centre. Our excellent museum has mounted an exhibition of true world class. The church has always housed the splendid standing monument to Il Porrina (1305). Always admired but only recently attributed to Marco Romano, a sculptor hardly known before now. This exhibition should certainly put him on the map. Apart from Il Porrina, there is a small head of a prophet, an Annunciation from the high altar of St. Marks (Venice) and a Crucifix, all of outstanding merit.

He is believed to have worked under Giovanni Pisano at Siena. Four plaster casts taken from figures in the Cathedral are displayed as Romano’s early work. By the time he got to Casole (via the Cathedral at Cremona) he was a very different artist. Like Lorenzo Maitani of Orvieto*, Romano turned away from the extreme stylization of of Pisano towards a more natural humanism. Indeed it may well be that Romano brought back the Roman influence to Sienese sculpture that was first introduced by Giovanni’s father Nicola, on the pulpit (c1265). Certainly his work in Siena has a classical flavour.

To make the case for Romano as a distinct, individual voice in sculpture Alessandro Bagnoli has assembled a mind boggling collection of works from as far afield as Berlin, Venice, Florence and Siena: such illustrious names as Giovanni Pisano, Tino da Camaino and Simone Martini are to be seen here in Casole. This show lays the foundations for a larger concurrent show in Santa Maria della Scala, (Siena) of later Sienese work “From Jacopo della Quercia to Donatello”. Both constitute a “must” for students of Sienese sculpture.

*Lorenzo Maitani was Sienese and would have been a contemporary of Romano’s if he ever worked on the Cathedral there. His work takes the same humanist road as Romano’s, I hope to extend my film about Maitani to include works of Marco Romano. We are righting art history here at Casole!

When that great prophet/seer of the modern age, Tom Wolfe, penned his last sentence to his long spoof on the art world “The Painted Word” (1975) he rather under estimated the power the word would continue to have on that pre-verbal activity – Art. Predicting the view from the year 2000 he wrote “With what sniggers, laughter and good humoured amazement will they look back on the era of the painted word.” But here we are in 2010 on the same road with the same cops directing the traffic!

Things move so fast today that a new “Story of Art” needs to be written every 10 years. I am one of the last generation to have been taught the history of art by the same artists who taught the practice when at Camberwell Art School (1956). A very different story to the one students hear today. In those days “Art History” was not generally accepted as a suitable subject for study. It was still being resisted by some of the older universities as being too subjective and open to the whim of fashion to be an area in which to educate young minds.

This essay is designed to show how right the old universities were and how tragic it is that resistance crumbled. Soon after I had left art school The Coldstream Report suggested that art history should be taught at art schools by professionals and that the students should devote 20% of their time to it. At the time we saw no objection to the idea. I very much enjoyed looking at pictures and the commentaries that went with them were often helpful. The majority of my contemporaries at Camberwell made a point of visiting the great museums of Europe to see the real thing and make up their own minds about what they saw. Art history did not play a part in the final exams which had only one written component that could be inspired by history or by purely practical craft considerations.

The reforms of The Coldstream Report brought in their wake a huge revolution in art teaching, partly because they coincided with the invasion of American Abstract Expressionism, (which was sweeping the board in Britain at that time) and partly because of the large and vociferous presence of art historians in art schools for the first time. I witnessed at first hand the resentment they caused when I was appointed to the new staff at Wimbledon that was destined to implement the reforms and raise the standard from diploma to degree level. Naively, I presumed that the art history I had received would continue to be a necessary element in the background of any potential artist. I soon found myself in conflict with the professionals, nor were the students in a mood to hear a different story of art from me.

The wisdom I had received from practitioners was roughly as follows:- Cave art was remarkably natural and lively because it was the product of ‘eidetic vision’ a presumed condition of thought prior to the coming of language and number that imposed abstraction on an important part of the brain. The cave men thought in terms of images which they seemed able to trace onto the walls of their caves, rather in the same way as Stephen Wiltshire demonstrated with his drawing of St Pancras Station at the age of 12. More recently he has taken a short trip in a helicopter over Rome and produced an intricate and remarkably accurate aerial drawing of that city! (see Youtube). This visual memory was a gift of nature that has been swamped by abstractions in the modern brain.

Since this abstracting shift of consciousness it has been a struggle for us to see nature as it is. We artists have to invent methods of tricking the mind to see clearly before recognising what we are looking at. Recognition means abstracting: abstracting distorts the perception! Observation is not that dull procedure that art historians suppose.

The progress of art has never been a smooth and continuous evolution but moves in fits and starts with long periods of stagnation or regression. In those days we received that message very clearly: all that is new is not necessarily good. Greek and Renaissance histories are outstanding examples, not typical. Other civilizations were swings and roundabouts illuminated by individual insights not mass enlightenment. Great periods of art are infrequent, and fugitive. That was a message that still rings true for me today but it seems to have been forgotten.

Greek civilization from 1000BC to 450 moved from the abstract symbols with which they decorated their pots (in 960 BC) through the stiff architectural, archaic figures inherited from Egypt and Babylon. Very gradually the figures became more naturalistic; till that magic moment around 500 BC when, with an unprecedented “leap of the imagination” the Greeks arrived at the balanced and natural pose of contraposto within 50 years! A short period at this apex of achievement was followed by decline into empty naturalism: that is the copying of surface detail without the necessary foundation of “form”: the abstract element found in all great art.

“Seeing form” was the desired outcome of a course of study in my day. Not everybody achieved it in three years. As a sculpture student at Camberwell I and my fellow students did nothing but study from life for two years, usually at life size. Models stood for 6 weeks in one pose as a norm. Composition was half of the final exam but we were not encouraged to practise that until a month before the exam. Observation was the be all and end all.

Such was the received wisdom. Though many years later I myself discovered that the great Greek “leap of the imagination” was nothing of the kind but simply the result of a technical improvement in life-casting. Nonetheless I continue to behave as if the Greek achievement was due to very refined observation. It is my belief that the artists’ main task is to keep the faculty of sight focused. The fact that the Greeks “cheated” and saved themselves no end of trouble has not upset that core belief. I rationalize my inconsistency with the thought that we need to be able to see what is going on out there in order to survive as a species. This is after all – fundamental; artists should not neglect their traditional responsibility in this. Look what happens when you leave it to art historians to decide where artists should go!

The organ of sight has not changed but the brain that receives messages from the eye and interprets them has changed beyond recognition. If that earlier brain is not to attrify completely, we better use it. Through the act of observing artists have come to realize the extent of that change. If the word-smiths did the same they would be better equipped for the task that society has foolishly wished upon them. Meanwhile artists should seize back the initiative in art they have lost through neglect.

During my student days it was de rigeur to accept Roger Fry’s dictum on Rome “that the loss of all her artistic creations would make scarcely any appreciable difference to our aesthetic inheritance”. I did not go along with that. My analysis of a portrait bust of Hadrian (1965 approx) has been the foundation of my syntax for “The Alternative Tradition”. I was intuitively aware of the great importance of Roman three dimensional geometry long before defining it.

This idea of ‘form’ was the very centre piece of art education in those days but by 1963-4 the existence of ‘form’ was being denied by the art historians. Their education was very different and they could not see it. My life’s work has been directed towards keeping the idea of ‘form’ alive. I use the word syntax to convey the yet more important idea that there is a grammar with which forms are held together in a structure.

Rembrandt’s drawings cannot be understood without the realization that his grammar is not the same as Renaissance grammar. His interest was concentrated on human expression in body language and he needed a more precise grammar of space in order to convey his findings. If we need evidence that the human ability to see is deteriorating intolerably, the steady sinking of Rembrandt’s reputation is the clearest possible indication of just that.

As I have written extensively on Rembrandt’s contribution to the development of the language of drawing www.saveRembrandt.org.uk I will skip that bit of history here.

If some tribunal existed in which I could present my case for reversing most of the judgments made by established Rembrandt scholarship over the last 40 years, I have no doubt that I could win. But alas there is no such tribunal, so the mighty establishments can ignore my abundant evidence with impunity.

I see the work of Brancusi as redirecting the attention to the ‘form’ basis of all art after a period of Victorian decadence when human sentiment had overwhelmed all else. As a student, I welcomed that new broom, but with hindsight I feel the pendulum has swung much too far. We need to get back to where our human interests truly lie.

*******************

Archaeologists have ignored my discovery that the Greek achievement was based on life-casts, as I have done myself. It is a pity that they have also ignored the two great chimneys I discovered at Athens and Olympia, which are necessary to explain the colossal Greek bronzes that we know once existed. These ancient chimneys are equal in effectiveness to the great chimneys that were built in the 19th century during the industrial revolution. Without them the Greek feats of casting would be impossible.

[It is now 10 years since I made these discoveries but no archaeologist has bothered to confirm or deny them using the array of scientific tests that they have at their disposal. The British School at Athens flatly refused to do so.]

If I may lay my customary modesty aside for a moment; I do find it strange that having rediscovered more important facts, more widely spread in the field of art history than any man alive, or dead*; that no student or department of Art History has shown the slightest interest in either the facts themselves, or in how those discoveries came about.

[*David Hockney, also trained as an artist, runs me closest in this respect. I much admire his pointing out the significance of the concave mirror but I have an earlier example of modern drawing (just after 1288) with a different explanation: an anonymous stained-glass artist tracing nature through glass (see The “Duccio” Window film). I am with Hockney on Caravaggio but feel some of his other examples are open to doubt. I find my own ideas more persuasive on Brunelleschi and Vermeer.]

As predicted there are plenty of absurdities at the Getty exhibition of “Drawings by Rembrandt and his Pupils”, some you can now see on line. When I receive the catalog there will be more on this blog.

Here are some notes on the Getty website comparisons to help you sort out the mess:-

1. Lievens, was a fellow student with Rembrandt at Lastman’s atelier. When they set up studio together Lievens was the better draftsman. Rembrandt learned more from Livens than from Lastman. (That is probably why Rembrandt only stayed with Lastman 6 months.) Eventually Rembrandt surpassed Livens as a draftsman. It is therefore misleading to include Lievens in this exhibition as he was not a student of Rembrandt’s. I accept the Lievens Rembrandt judgement. NK

2. Flink, was a student of Rembrandt’s. He was a fairly good draftsman and painter. However, his drawings are not similar to Rembrandt. Judgment accepted NK

3. Bol a pathetic student of mythological subjects was unable to learn from the master in spite of brilliant lessons in drawing (see Hagar and the Angel – “One does not Know whether to Laugh or Cry”). see also “The Finding of Moses” & “Pomona”. Bol wisely specialized in portraiture later.Both these drawings are clearly by Rembrandt; look at the hands, feet and fur hat. Bol’s “brilliance” is always due to the recent robbery of Rembrandt’s portfolio by the “experts”. Judgment absurd, refuted NK

4. Landscapes – I do not comment on the landscapes.

5. Renesse was one of Rembrandt’s better students. Certainly a student NK

6. House on the Bullwark – I do not comment on the landscapes.

7. Eeckhout, was a diligent student of Rembrandt’s. accepted NK

8. Hoogstraten was a student of Rembrandts. (I hope you will recognise mundane version of the same set in a barn as in my movie of “The Adoration of the Shepherds)”. Judgement accepted NK

9. Raven may have been a student of Rembrnadt’s. However, he had no drawings to his credit until experts discovered his name on the back of a Rembrandt drawing (presumably because he owned it). It is a complete disgrace that Raven was ever considered the author of this drawing. Note that the model is again Hendrikje Stoffels. Is it likely that Raven and co get invited in to draw Rembrandt’s mistress? absurd, refuted NK

10. Unkown student -this drawing is clearly by Rembrnat absurd judgment NK

|

|

As an artist working primarily from life, I am acutely aware that nature provides the observer with a hugely complex amount of visual information so any ‘gadget’ or aid to seeing which simplifies the process is always of interest. Having produced this painting with the use of two mirrors, I can appreciate the practical advantages:

1. The complete image, as seen in the easel mirror, is considerably smaller than ‘real life’ and it is all in focus, making it easier to judge the final effect. As a result, the spacial relationships and colour balances within the painting can be fully considered and explored before brush is ever put to canvas.

2. Using a present-day mirror reduces the light areas in tone making the judgement of relative tones on the palette much easier – a more primitive 17th century mirror would have reduced them still further.

3.The artist can position his easel in the same light that bathes the subject of his painting. This is a decided advantage in a small studio, particularly if the artist wants to depict himself from behind.

My own experience of the camera obscura is that it achieves none of these things and would actually hinder the painting process as the artist needs to see the paints on his palette in the same light that he views the painting. However, an image through a lens could well have influenced Vermeer’s vision, such that he chose to paint objects slightly out of focus, as an extra technique for creating his reality.

Close study of Vermeer’s interiors reveals him as a precise thinker and it seems to me that he worked slowly and thoroughly making few changes as he went along. I also think he was well ahead of his time in the way he created atmosphere with colour composition and the effect of light filling the spacial volumes.

All artist’s have their different methods. I suspect that Vermeer elongated the orthogonals in the foreground to create more spacial volumes in his interiors, as, for example, in “The Music Lesson” painting. The traditional chequered flooring would have been a great help for that.

- The Music Lesson, Vermeer

The historical facts of the time lead me to think that, inevitably, he would have investigated and experimented with any new optical tools but I think it is highly unlikely that he actually used the camera obsura images to paint from.

WEB SITE: www.anneshingleton.com

On the 20th of January I gave a talk to the British Institute of Florence as part of their cultural programme. The subject was “The Museum of Artists’ Secrets” housed here at the Centro d’Arte Verrocchio. The talk was very well received.

A lot of artists were present and asked a lot of good questions; I hope I gave them good answers. Certainly many promised to come and visit the museum for themselves. Seeing is believing! In the time available (one hour) it was only possible to mention in a cursory way most of the exhibits.

I started with my discovery of the use of life-casts in ancient Greece from around 490 BC (Pliny tells us that life-casting was invented around 350 BC by the brother of Lyssipus). This produced some sceptical questions. Unfortunately I had not brought exhibit No.1, the wax foot cast from life, which I regard as the evidence that puts the matter beyond reasonable doubt. Charles Cecil, who runs a very successful school in Florence, promised to investigate the matter further either with a visit here with his students or for me to visit his school.

I then gave a brief summary of the geometry of Roman portraits with photos of the carving process for the bust of Hadrian from the British Museum. And demonstrated how this geometry had become part of the syntax of the Alternative Tradition in European art: the tradition of Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt and Degas. I should perhaps have included Giacometti in the list of examples.

I gave a long build up of the importance of Rembrandt’s drawing B1121 (included in this blog) and finally shocked them with the news that it had been re-attributed to Aert de Gelder. At that point I made a strong bid for their help in making the RRP and the drawing “experts” pay attention to what I was saying. I have never been so clear and forceful on this point before and it really seemed to strike home. ( A young Dutch woman offered her help at the end and I promised her a DVD to help her on her way.) Richard Serrin, a well known painter, said he had been studying Rembrandt for 50 years and what I had said made a lot of sense to him. He paints rather Rembrandtesque subjects.

It was gratifying that so many of the painters of Florence came and were excited by these new interpretations of Rembrandt’s artistic character. I certainly stirred them up. I finished with two excerpts from our DVDs of Maitani and Rembrandt. I had to cut “Duccio’s Window” and Simone Martini as I had gone over time. Wine was served to all afterwards and I was presented with a bottle of Brunello for my pains. We drank it with great pleasure at supper. A good night out.

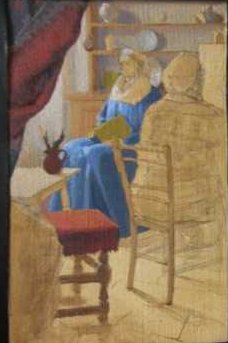

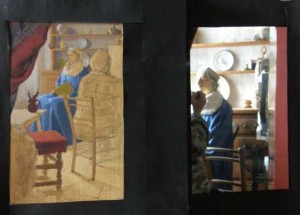

After some days of very poor light Anne has very nearly completed the painting. Using the size of the image as seen in the easel mirror the painting is remarkably small. Although the necessary space for a studio using the mirror method is very small the visual distance from the main subject (Rembrandt and side-board) is actually 3.95 m, this is because the light hits the large mirror then the second mirror on the easel and finally comes to her eye. This distance causes the small image.

Anne's Painting

Our big mirror was narrower than Vermeer’s, accounting for our somewhat cramped composition. By using a wider mirror than we have behind, the angle of vision could be widened considerably.

The large areas of fabric or carpet that one finds in the foreground in many of Vermeer’s paintings was there to provide an undemanding area of the painting that would cover over the area where he would have seen himself directly reflected in the easel mirror. In Anne’s case we see her right shoulder blotted out the left-hand corner of the picture which she then painted with green and striped fabric following Vermeer’s example. This is another strong argument in favour of Vermeer’s use of two mirrors rather that the camera obscura. With the camera obscura the artist is hidden behind the lens, so the image of the subject would have been complete.

I feel that Anne’s painting is very Vermeer like; in the simplifications of Rembrandt’s face for instance. Also in the very accurate and simple recording of the patches of light coming from the objects on the shelves behind, which gives precedence to the light rather than the description of the object itself. This is particularly typical and very much the result of the method of observation. Until someone comes up with something more Vermeer-like observed in a camera obscura; I am persuaded that this method, which was strongly hinted at in “The Art of Painting”, was in fact Vermeer’s method.

For me Vermeer is the first painter to be primarily concerned with light. It can be no coincidence that the inventor of the microscope lived in Delft. He was Vermeer’s contemporary, he was the first to see microbes swimming in water. The telescope also was a recent invention and was being improved throughout Vermeer’s life-time, bringing revolutionary knowledge to mankind through the medium of light. Light is the prime way we receive the outside world and Vermeer investigated its properties (focused and unfocused) with single minded “scientific”devotion. It was for this reason that he was obliged to use the camera obscura: to study unfocused light. He could have used it also for the planing stage of his paintings but two mirrors, or the better known methods mentioned above, would also have produced the same perspective effects.

|

The photo shows a reflection in the easel mirror (above) for comparison with the same in pewter (below). The pewter is a poor substitute for a 17thC silver-backed mirror which we believe Vermeer would have used but we do not possess. The pewter gives a tonal range that is too reduced to be of practical assistance to a painter. Silver turns black over a period of years in light. Experiment could show whether Vermeer's mirrors were new or old, certainly they would have been silvered. |

The palette-knife is held against the reflection in the easel mirror to aid the process of matching the colours and tones. |

Since the publication of “Vermeer’s Camera” by Philip Steadman it has become accepted that Vermeer used a camera obscura. Steadman is an architect by training he is most knowledgeable about the mathematics of drawing. His book is a very thorough review of the literature on Vermeer. He rightly opts for Lawrence Gowing as the leading expert. Many may not know that Gowing was for the first half of his career, a fine tonal painter. From his book it is perfectly clear that Vermeer was his role model.

Gowing is very much more in touch with what a painter gets from Vermeer than Steadman. Gowing writes “the optical basis of his method is most visible not in the planning…….so much as in the tonal recording of certain passages” later he describes Vermeer’s work “as statements of light purged of any other content”. It is this essence of Vermeer that “Vermeer’s Camera” fails to address. The camera obscura would be a positive handicap in achieving these qualities. We can be quite certain that Gowing would have taken one look at the “dark images” the camera provided and turned away disappointed.

Most recent authorities agree that the camers obscura was used, and I am certainly persuaded that it was but my interpretation is different to Steadman’s. The eye automatically refocuses. However determinedly one may try to observe objects out of focus one fails to see anything approaching Vermeer’s out of focus effects, which must be deliberate.

Steadman shows that Vermeer could have been in touch with the most advanced optical experiments of his day. The anatomy of the eye was sufficiently understood to know that it, like the camera, must also go out of focus but only the camera allows one to study light in this condition. This is Vermeer’s prime use of the camera. The planning stage could equally well have been done with Durer’s screen and fixed eye point or Alberti’s net, or Brunelleschi’s constructional method, as Steadman readily admits.

Here we are experimenting with an arrangement of mirrors which is cryptically described in Vermeer’s largest painting “The Art of Painting”. The interpretation was first proposed by Willenski. I arrived separately at the same conclusion through my interest in artists’ use of mirrors and wrote it up in 1980 after conducting the simple experiment which Willenski failed to make. It works. Incidentally this arrangement can also explains the geometry of the results.

Essentially we are pursuing Willenski’s line of thought into the practice. Anne Shingleton, who is a painter trained in the old school (by Simi) and who has 30 years experience of painting light, is in the driving seat.

Here in the library of The Centro d' Arte Verrocchio we see Anne sitting between two mirrors. The big one behind her is somewhat narrower than that used by Vermeer. It is 53x130cm with generous bevels and a frame, which rests on the floor. The plane of the mirror is very nearly parallel to the end wall. The smaller one on her easel, for simplicity is masked off at 26 high x 16cm. wide. The angle between the two mirrors is approx 30 degrees.

Her first reaction on looking at the image in the second mirror on the painting easel was. “Wow, I would like to try it, it seems such a good idea”. She went back to her studio and immediately produced a painting with the method, she said “ the experience has been of great value and has made me look at Vermeer’s work with a completely different eye. The main advantages of working in this way are :-

1. You see the whole composition in the second mirror and so you can move objects around to achieve a pleasing colour and tonal balance before you start.

2. The image in the mirror is conveniently small in comparison with reality, making it easier to judge the balances within the composition.

3. The image can be traced off the mirror, or as it’s viewed sight size can therefore easily be drawn on to a canvas.

4. Above all the tonal range can be analysed much more easily because the intensity of the light is reduced by being reflected off two mirrors and is not thrown out of balance. (Two 17thC mirrors would have reduced the light still further.)

5. The objects are quite far away so the details are more difficult to observe but for a painter this is a definite advantage as the this helps perception of the main light and dark areas.

6. The heavy drape in the immediate foreground also helps the artist judge the more subtle area of light by providing the darkest darks and sometimes the richest colours for comparison within the picture frame.

The artist's task is to mentally compress and adjust this tonal range down a series of tonal notches to that which his paints can span to produce the same scene, maintaining all the time the delicate relationships between all the middle tones. Here we see the painting (left) and the reduced image in the second mirror (right).

Judging the tones of a scene and converting them into paint for a painting is a skill that requires much practice to master. There are many approaches. When we look at a scene with the naked eye we see the lightest areas and the darkest areas and the rest is made up of all the multitude of tones between. (Our eyes also adapt in many ways, for example by changing the width of the pupil, allowing us to work with a really wide tonal range.) Our eyes are wonderful machines to perceive light.

Simply put, the task of the painter is to trick the eye into seeing the same scene, but reproduced using the darkest paint, black, to represent the darkest dark, and the lightest paint, white, to represent the lightest light, and to reconstruct all the tones in-between. Looking at a scene with the naked eye it is quite difficult to imagine, for example that the bright shine on a white, porcelain jug, would have to represent the white pigment on your palette, when the actual white pigment held up on a palette knife in front of the jug actually compares in tone more closely to the lit side of the jug. Thus, the artist’s task is to mentally compress and adjust this tonal range down a series of tonal notches to that which his paints can span to produce the same scene, maintaining all the time the delicate relationships between all the middle tones. The visual reality is reconstructed in painted areas of tone that balance well with each other on the canvas and create the illusion of the same scene. Mirrors which help reduce the light intensity are certainly a useful tool here.

To judge all the light and dark values the artist uses a palette on which to mix up the colours. The colours are arranged around the edge. It is portable because the palette must be seen in the same light that the canvas is lit by. I do not think an artist could look at a very lowlight image in a dark box and then return to mix up the colours in the daylight outside the box. It would be a very impractical way of working, since for each mix you would be comparing many times, and there would be a pause each time as your eyes adjusted to the large change in light intensity. This is another advantage of the two mirrors over the camera obscura.

I have recently studied an image through a camera obscura and did not find it remotely inviting to paint. Steadman’s explanation of the necessary technique with blinds sounds too complicated by comparison with the ease of this mirror method.

The first days work was spent in arranging the composition using Vermeer’s colour schemes as a guide. The back mirror is only 3.10m from the wall. A remarkably small studio space. And this is perhaps the strongest argument against Steadman who requires a palatial studio for Vermeer’s camera. Could Vermeer, who was driven to paying his baker’s bill with a painting and died in debt, possibly have afforded such a studio? Think of the heating bills in Holland in the winter.

This blog makes a case for starting again with the neglected art of observation, particularly the art of observing human nature. Humanism: how the spirit of Man expresses itself in the physical world. Humanity is the most interesting subject because it concerns us most deeply. It was the prime subject of art for the 40,000 years prior to this passed century. The subject never pales because life moves on and art changes with it.

Unfortunately the writers on art are somewhat outclassed by the artists themselves when it comes to observing. Some artists have spent their lives studying it. The critics protect their self esteem by avoiding this subject matter and concentrating on abstract ideas, where they feel safer.

After 100 years of this bias in public notice it is little wonder that observed art, the art that Everyman can understand, is in steep decline. Through habit we try to take seriously establishment art (Art Bollocks as it is so justly dubbed by the Jackdaw Magazine) but the effort is seldom worth making. Their art is only of interest to the few who are making money out of it. Art matters because seeing and responding to the world about us is essential to our very survival and art is our best educator in this.

Rembrandt scholarship is used as a demonstration of how far the rot has gone. The scholars seem completely out of touch with human feeling. Having spent their lives in company with the greatest artist to observe humanity, they have so undermined his reputation that students can no longer trust him. Observing the results, they must represent the steepest artistic decline in human history. It is no coincidence that the decline dates from the rise of Art History as a political power. Artists have been too lazy or naïve to direct their own evolution. They have left it to the likes of Serota at the Tate and the Rembrandt scholars.

It is going to be very difficult to stop them but that is what must happen. The Jackdaw and the Stuckists have unearthed sufficient evidence to put many of them “away”. This is well worth considering as a tactic. I have shown that the Rembrandt scholars are simply protecting themselves, their tactics of head-in-sand have worked but done immense damage to the cause of art as a result.

In a nut-shell – my article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” published in the Burlington Magazine (Feb.1977) demonstrated that the hypothetical development of Rembrandt’s style created by generations of Rembrandt scholars, was no longer tenable. The variations in style were due to Rembrandt’s responses to the very different stimuli of reality or the reflection of that reality in a dim polished metal reflector (glass of the necessary size did not exist in Rembrandt’s day). Below I show three illustrations from that article to clarify this point. Many more examples are available (link to www.saveRembrandt.co.uk)

Take this link to see a 5 minute film which shows the same use of mirrors with two of Rembrandt’s paintings: “The Adoration of the Shepherds” in London and in Munich. The London one (observed in a mirror) has been discredited by the “experts” of the Rembrandt Research Project though it passed all tests that The National Gallery put it through. It probably now resides in the basement there.

The briefest perusal of the three catalogues put out by the three main collections of his drawings (The British Museum, The Rijksmuseum and the Boymans of Rotterdam) show that the “experts” are still spending all their time pretending to put dates on drawing according to style – making no attempt whatever to look at the human aspect which was Rembrandt’s chief concern. Their lack of aesthetic discernment pales into insignificance beside their lack of ordinary common sense. Either the authors are too dim for the job we entrust them with, or they badly need psychological help. The same applies to the regiments of Rembrandt scholars elsewhere.

ARE THE NEW FACTS ABOUT REMBRANDT EVER DISCUSSED? IF SO

HOW ARE THEY COUNTERED? WE WOULD LIKE TO HEAR..

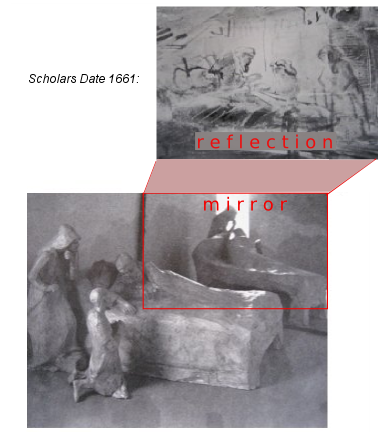

The photo is of a maquette to represent Rembrandt's studio set up with live models and a mirror for his series of drawings of Isaac and Jacob. Below is a drawing that scholars have dated 1652 ( Rembrandt's classical style) and above a drawing they date 1661 (his mature style). The photo demonstrates how both were drawn from the same seat in the studio, under identical lighting conditions and very nearly the same group of models, only Rebeccah has moved. Common sense suggests they were drawn one after the other- not after a gap of 9 years. Clearly the style of the two drawings is very different but the difference can be very well explained by Rembrandt's differing response to reality (below) and reflection in a dim mirror (above). This same difference has been demonstrated many times in Rembrandt's work. eg. The Adoration of the Shepherds, The Dismissal of Hagar and this series of drawings of death bed scenes. Konstam's article “Rembrandt's Use of Models and Mirrors” was published in The Burlington Magazine in February 1977. That article invalidated stylistic criticism but the scholars continue to destroy Rembrandt and waste everybody's time with their out-dated theories.  Scholars date 1652 |

|

|

We have recently completed a DVD about one of the all time greats in sculpture. You are unlikely to have ever heard of him. He started his great work as architect and sculptor on Orvieto Cathedral in 1303 and some of the sculpture was in place by 1307 that is some years before Giotto’s Arena Chapel or Duccio’s Maesta. He is so original and advanced technically that he does not fit the mould of art history’s development, so it is easier to leave him out all together!

Technically his work in relief is the missing link between the Pisani (Nicola & Giovanni) and Ghiberti’s “The Gates of Paradise” on The Baptistry in Florence. More importantly he speaks to us through a common humanity more immediately and comprehensively than any of his contemporaries. His observations of humankind are truly delightful. He retells the Bible stories with gravity, humour and even one feels with a touch of criticism for God’s pre-feminist attitude to the fair sex.

How could such a master be neglected? It was in answering this question that I believe I have stumbled upon the great hole in art criticism today. See “A Manifesto for New Humanism” below.

The sculptor’s name is Lorenzo Maitani. You can find splendid photos of his work in “La Facciata del Duomo di Orvieto” (SilvanaEditoiale 2002) or in our DVD see below. If you go to Orvieto take binocculars, the reliefs start at eye-level but go up about 10m, there are 112sq.m of them!

DVD will soon be available through the Orvieto Tourist Board.