I have been silent for quite a time because I have been busy preparing a talk for PINC conferences. It has been very demanding trying to put all that is necessary to see the greater Rembrandt, into 20 minutes for a lay audience. Some may not even know that Rembrandt’s work has been cut by more than half in the last 40 years by the experts. I think I have pulled it off.

I will be delivering the talk in the PINC series on May 17th. I will publish it on this blog soon afterwards. It is most gratifying that the Rembrandt Research Project has collapsed before finishing their labours; people may at last be ready to listen to my lone, dissenting voice.

Info @ PINC.nl

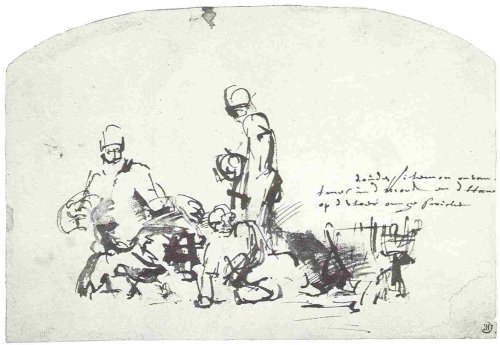

Front Cover of Catalogue

There are so many howlers in the expert assessment of Rembrandt’s nudes that I will limit myself to the two splendid drawings reproduced on the cover of the Getty Catalogue. On the front, is a drawing that is still accepted as by Rembrandt; on the back cover is a better drawing which is now re-attributed to a moderately accomplished student, Arent de Gelder. Both drawings are quite obviously not only by Rembrandt himself but of his mistress, Hendrijke Stoffels: furthermore these drawings are quite clearly investigating the pose of Rembrandt’s painting “Bathsheba” in The Louvre. No previous reputed scholar has had the effrontery to doubt either before.

Nigel's Maquette from back of Getty Catalogue

It is almost besides the point that Rembrandt clearly loved her – we love her – because she is reality framed, simplified, clarified to penetrate the human brain. Through hinted geometry we can find our way across that soft, once muscular back, the nuances of the tone in the shadow, as the light strikes across her back, allows us to caress every limp muscle and protruding bone. This drawing teaches us to love and accept nature as she is – not to fly off to some imagined stereotyped goddess. This is Rembrandt’s gift to us: life as it is – miraculously lovely.

The technical basis for our grasp of what Rembrandt is drawing is straightforward and founded on an ancient tradition of form making. We find forms of geometry hinted at in art. Rembrandt himself was greatly attached to Roman portraits, he owned 30 of them and filled two books with drawings of them. Alas these books have been lost, last heard of in the sale of his goods in 1656. (I have made a DVD which explains Rembrandt’s reliance on three dimensional geometry more fully.)

Here in fig.3 below you see how the figure fits into a block of space (suggested by the plastic frame). The figure conforms to the two sides of the block and her stool gives us the hint that the light confirms. See how her head reaches over to touch the light plane of the block, as does most of the figure. The shadow side is parallel with the back of the stool. Once you see the space every mark that Rembrandt makes on the page is accurately legible within that space. He gives all that is necessary for a sculptor to find the figure in a block of stone ( my figure is modeled in clay). Because the space is so clear the forms within it can be perfectly understood.

Maquette within the block

In fact I prefer this pose to the final version of Bathsheba; the turn of the head away from the indecent suggestion this married woman has received from King David, seems superbly appropriate. We cannot see the letter that is needed to explain the subject and it is probably this that made Rembrandt go for the front view.

While the drawing that is still a Rembrandt is clearly of the same model in nearly the same pose, the geometry is not quite so secure. One can see that Hendrijke has slumped forward a little during the pose. Her distant shoulder has been redrawn lower down. This would have necessarily lowered and swung forward that breast as well but Rembrandt has not made that adjustment, so the front plane of her chest does not quite mesh with the side plane. A very small slip, which may be difficult to see and which those that can see, can easily forgive.

Thus the Getty“experts” are suggesting that de Gelder is more reliable in his geometry than the master. They go on to say “ de Gelder” (the great drawing) “is weaker in the illumination and the rendering of form… above all, it is highly improbable that one artist would draw the same model from the same pose twice”! Highly improbable as it may seem to the “experts” I do it whenever my enthusiasm is aroused. Moving round the figure demonstrates the sculptural side of Rembrandt’s genius. Mr. Giltaij, of the prints and drawings department in Rotterdam, finds “the modelling of the back gives the impression of being over detailed and cautious…the contours (of the figure) are weak and hesitant” such appalling misjudgements are confounded by my ability to make sculpture from the drawing.

In the Getty catalogue the “experts” re-attribute three other former Rembrandt nudes to de Gelder, although the one “sure de Gelder” according to them, is of Jacob being shown Joseph’s blood stained coat (a typical and much tried Rembrandt subject. It is not a great drawing but nonetheless I would guess Rembrandt’s. How can they guess it is by de Gelder with no drawing to compare it with?) They must be stopped! Now!

Form is a somewhat hidden ingredient of art. Brancusi made it his life’s work to expose form to public view. He dared to call an egg a head, thus demonstrating the classical Greek form of the head. He made these abstract simplifications the final aim of his art. It is also generally agreed that Brancusi was in strong reaction to the work of Rodin and others of his generation, whose work by contrast seemed to be formless but it is not.

Rodin very seldom subscribed to the simple Greek idea of the head. He followed a different tradition of form that we might designate as Roman, as it made its way into Europe following ancient Roman conquests. Very many great artists followed the Roman tradition subconsciously. Rodin would have received its influence not only from the Roman work that abounds in Europe but from many French devotees from Gothic times onwards – Clouet and Houdon were masters of it, and in his own time – Degas, Lautrec stand out. Today’s art critics and historians need to become more aware of this second tradition of form , which is, if anything, more prevalent than the Greek tradition because it is much more useful for analyzing the complexities of nature.

I think it would be true to say that no artist can be considered even of the second rank without subscribing to a tradition of form. Form is a vital ingredient of art. Form is nature simplified so that the human mind can comprehend it. More important than form is the development of a sense of structure.

Structure is the logic with which multiple forms are held together. In sculpture structure is usually to do with the way the building blocks defy gravity. In archaic figures, for instance, the structure is the same post and lintel architecture as the temples they adorned. Classical form is based on the simplified cylinders and cubes which underlie Greek classical sculpture. Their structure is defined by what we all know of the human body – what it can do – and what it cannot do. This is the form that art historians more or less understand. But Rembrandt found that the classical Greek tradition had descended into a stale academicism, moreover, it was too crude spatially to deal with the subtle psychological relationships that interested him.

Rembrandt’s greatness as a draughtsman rests on his extension of the Roman tradition. Rembrandt studied the solid that was so exquisitely defined by the geometry of Holbein and the Romans and extended that geometry to include the intimate space that is so essential in reading psychological situations in the physical world. Rembrandt not only owned 30 Roman portrait busts, he filled two books with studies of them! Alas, these books have been lost.

If Rembrandt scholars could understand that this structuring of space, is where Rembrandt’s greatness lies; we could return to the complete, great master we once knew. Rembrandt’s style of “handwriting”, which so dominates Rembrandt studies today, is quite irrelevant to his greatness. Added to which my Burlington Magazine article of Feb. 1977 demonstrated that their understanding of Rembrandt’s style of handwriting was absurdly wide of the mark. 33 years later, instead of those grave mistakes, we have the atrocities of the Getty show (as outlined in Getty 1- 4 below) which have deprived more than a generation of artists of their greatest master of gestural expressiveness: body-language, and much else. They must be stopped!

I am working on a DVD which I hope will help the experts on their way to a better understanding.

There is so much I disagree with in the Getty catalogue it will be quicker to name those parts with which I have no argument. There are two students of Rembrandt who though not great are perfectly decent workaday draughtsmen. Their names are Renesse and Hoogstraten. Their style of drawing is not like Rembrandt’s and therefore they have not benefited from the recent handout of drawings that the “experts” have de-attributed from Rembrandt’s portfolio.

I do argue with two others who come into the same category of good, workaday draughtsmen whose work does not in the least resemble Rembrandt’s but have nonetheless benefited from re-attributed Rembrandt drawings. Eekout and Flinck. By what convoluted argument they have been so lucky, the catalogue does not explain.

There is the strange case of Carel Fabritius who was a fine painter but left us no certain drawings. This is not unusual as some painters paint over their preparatory drawings, which were done directly onto the canvas (like Hals and Vermeer). CF has been gifted two very fine and typical Rembrandt drawings, on what grounds we are left to guess. Without comparisons there is nothing to argue about. But he is likely to receive more of the same in future madness.

Johannes Raven, is a comparative newcomer to Rembrandt’s supposed stable of assistants or students. He wrote his name on the back of a drawing, which while not being one of the greatest is almost certainly by Rembrandt. (Rembrandt did many careful drawings in preparation for his etchings, they have all been re-attributed. This looks like one of those.) Had Raven written his name on the front we could agree that he was at least claiming it as his work. However, by signing on the back, I would guess he was only claiming ownership. Surely we all write our names in books for that purpose. Luck was on Raven’s side, the “experts” have overlooked that possibility. A whole raft of life drawings by Rembrandt (mostly of his mistress Hendrijke Stoffels), are now re-attributed to Raven!

Most outrageous of all is the case of Ferdinand Bol whose work as a draughtsman scores a lot lower than the category of decent, workaday. Bol has benefited from a large number of really good or great drawings by Rembrandt. Rembrandt once gave him such a magnificent demonstration of draughtsmanship relating to his, Bol’s, painting of Hagar and the Angel. If, with eyes tight shut, we attribute that drawing to Bol there is no reason why he should not have done other great Rembrandt drawings. With eyes open this mirage vanishes. But the fact remains that at this moment Bol appears great, due to gross misjudgements. With little merit, he has had greatness, thrust upon him!

Those, like Bol, that have benefited from the handout, very much diminish Rembrandt’s stature and obscure his unique contribution to the art of drawing. We now see Rembrandt surrounded by a team of gifted mediocrities, who have made quantum leaps on occasion and who will in due course inherit more of Rembrandt’s greatness, unless, of course, we can unseat the present regime. The uncanny feebleness of modern scholars can only be the result of promoting the most loyal and unquestioning students over several generations of scholarship. They don’t seem to possess eyes or minds of there own. They religiously follow the now untenable theories of their teachers.

Benesch told us that Rembrandt’s “inner vision (of the Biblical subjects) was as if he had seen them in reality”. My experiments demonstrate that he “produced” them in reality by the use of models and that is part of the reason why they are so much more convincing than other artists’ inventions. Unfortunately, for generations we have been fed the idea that what is imagined is superior to what is observed. (Rembrandt himself would have laughed at such a notion.) It is therefore, difficult to persuade today’s art students that they should follow Rembrandt’s example and feed their imagination on reality. Thus, the mythology of Art History has undermined a well tried road to improvement. The “imagination” mythology is yet more dangerous because it diverts our attention from the real world in which we live. Without attention we will falter.

CONCLUSION I hope with these four critiques aimed at the most recent example of Rembrandt scholarship I have conveyed the urgent need for change.

The evidence I have put before you was all there in my Burlington article of February 1977, I have simply amplified it to the point where one can claim that there is no possible room for further doubt. Rembrandt did use large groups of live models, dressed in his extensive theatrical wardrobe, as in the “Adoration of the Shepherds”(see film on YouTube where it is possible to compare the paintings with the photos of the maquettes) on many occasions. An unbiased eye could have deduced the same from a fairly casual perusal of his collected drawings. The mirrors were a proof, which has still not been acknowledged. It needed a desparately biased collective eye to deny the obvious. Many thousands of students have had the wool pulled over their eyes since 1977. This must stop!

Rembrandt is universally regarded as among the great seers of humanity:

a creative genius. It is worth inquiring how he achieved this

pre-eminence. Unlike his chosen artistic partner Lievens, he was not a

child prodigy. In fact, his early works give no inkling of the genius he

was to become. It is not easy to decide who was the major influence on

his development Lievens or Lastman. Lastman was the master in whose

atelier Rembrandt and Lievens met as students.

I tend to favour Lievens; as Rembrandt’s very short stay with Lastman (6

months) suggests antagonism of some kind. Rembrandt made numerous copies

of Lastman’s work. Perhaps these copies were a compulsory but resented

part of the Lastman teaching. Rembrandt’s copies of Lastman are also

criticisms. On the other hand he learnt rapidly and uncritically from

Lievens. His early Leyden works are very strongly influenced by Lievens.

Rembrandt and Lievens worked together from nature, perhaps this was the

crucial difference between the methods of teaching and speed of

assimilation. If this is so Rembrandt had learnt the prime lesson of the

great leap forward in science. Observing nature directly was the secret

of that success. Furthermore, the documents of Rembrandt’s life give

incontrovertible support to the idea that working from nature was

crucial “anything else was worthless in his eyes”. It is difficult to

see how scholarship came to the opposite conclusion: that Rembrandt

imagined his Biblical pieces. Even today scholars remain convinced of

that idea. Perhaps I should attempt to explain their strange behaviour.

[There are two aspects of recent scholarship that are entirely

undermined by my re-discoveries:

1. the dating of drawings by style is no longer tenable. The changes

in style are demonstrated to be the result of either different

media or different stimuli: reality, reflection or imagined.

2. the vast literature on the iconography of Rembrandt and his school

becomes a laughing-stock. All that speculation about the shifts in

emphasis found in the student works are explained by the differing

view point of the physical groups of models in Rembrandt's studio.

These are not mere peccadilloes that can be lightly laughed off. The

scholars are used to being taken seriously, they are entrusted with our

artistic patrimony. These two major gaffs undermine their status as

experts.]

**************************

An unusual characteristic of Rembrandt’s behaviour is his acceptance of

failure as the possible outcome of an experiment. He did not tidy away

his failures as others did. If you accept the greater, more prolific

Rembrandt that I propose, it could be said, he advertised his failure to

draw from the imagination. I interpret this “carelessness” as a

wonderful openness and generosity. He seemed to want us to know how he

had arrived at the summit; perhaps, he did this so that we could emulate

his behaviour and push further with his insights into the working of the

psyche in the physical world.

Rembrandt earned a reputation for leaving his work unfinished but was

unconcerned. Furthermore, only about twenty drawings can be identified

by signature or handwriting, the rest we have to chose according to our

understanding of his aims and style of thought. Rembrandt’s confidence

in his own unique character as an artist was justified. The sensibility

of our “experts” is the issue. For instance ex. 7 & 8 are both typical

of Rembrandt’s concerns and his habits as an artist. The little dog in

Ex.9 is a veritable Rembrandt trademark! He loved dogs and could

obviously draw them from memory, unlike his angels.

Example 7

No.7 has been re-attributed to Drost, in spite of the fact that

Rembrandt did an etching of precisely this subject. The treatment of the

clasped hands of Tobias could hardly be closer to the hands of his

mother in the drawing still accepted as a Rembrandt; reproduced in the

catalog opposite for contrast. The angel has that clumsy feel of

Rembrandt constructing from imagination rather than observing. All the

other figures express shock as we would expect from Rembrandt.

Example 8

Ex.8 is re-attributed to an unidentified student of Rembrandt. We are

therefore unable to compare with known examples. We can be certain that

the central group would be much closer to the Rembrandt on the opposite

page. In fact, the “mocker” is so typical of Rembrandt and better

realized here, than in the accepted drawing. If I was going to talk of

the style of this figure I would be referring to it’s compactness, its

sculptural quality, it’s balance, it’s geometry and it’s expressive

quality. The handwriting is of no importance to it’s quality as art. If

we talk about the style of Dickens we are looking at his entire

philosophy, his use of words, not his handwriting! Why can we not get

Scotland Yard onto these drawings to compare inks, pens etc. they would

make a far better job. Our experts are to be pitied, not to be listened to.

Fortunately, Rembrandt signed and dated his etching plates. Therefore

the etchings and paintings give us a fairly reliable foundation on which

to build. They give me the feeling of a man so absorbed in his journey

that he will sacrifice whatever is necessary in craftsmanship,

draughtsmanship or detail to keep up the momentum. “A picture is

finished when the painter feels he has expressed his intention in

it.”(Rembrandt as reported by Houbraken). What an excellent example for

us all: this is why his intentions are so obvious to some of us. His

drawings should be seen as steps towards finding his intention: that is

his interpretation of the Bible story. Ex.1.expresses a particular

relationship between Lot and the Angel, this is Rembrandt at work with

his practical brand of imagination: sodomy is a male concern, forget the

pillar of salt.

There are many important lessons we can learn from Rembrandt:-

One, is not to be frightened of failure, we need to learn to acknowledge

our failures and then learn from them.

A second lesson is to learn to feed one’s imagination. Rembrandt did

this by producing model groups in his studio; the closest he could get

to the actual occurrence (the Bible story). This was a part of his art.

His unique success in depicting human relationships lies in the physical

“production” of the re-enactment. “He would spend a day or even two

adjusting the folds of a turban until he was satisfied”. We can presume

that he spent equal time arranging his actors.

Third, was his drawing strategy: he put top priority on the disposition

of the masses in space. This is how the physical pose expresses the

spirit of his protagonists so brilliantly. Perhaps, this can be

appreciated more fully by those who practice drawing or acting

themselves. The scholars’ study of style amounts to no more than the

study of the idiosyncrasies of his handwriting, which they have then

misinterpreted and over played.

The scholars’ search for “ the leaner, fitter Rembrandt” has pruned away

most of these valuable lessons for artists. We must learn to see

Rembrandt’s drawings as he himself saw them: as journeys of discovery,

which only occasionally end with the hoped for, pot of gold.

Surprisingly, Rembrandt did not sign the jewels, he signed his gifts in

autograph albums etc. which were often from imagination

Example 9 Homer

and therefore mediocre. He unwisely left it to the taste of the connoisseurs

to recognise his true hand. He even left proof of authorship on his

least satisfactory products.

Ex.10, B.960 Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis, an illuminating inability. Rembrandt has had to write the story that the drawing fails to tell.

The museum“experts” tend to see the drawings as valuable items in a

collection, and their job as to weed out the duds. I hope I have shown

sufficient reason why we do not want that weeding to continue; we lose

much too much in the process. Tragically today’s scholars are not good

at weeding. Through their pruning over the last 100 years we have lost

sight of many of Rembrandt’s greatest drawings . Their confidence swells

as the great Rembrandt shrinks; they must be stopped!

My experiments with maquettes and mirrors have given me a fresh insight into Rembrandt's modus operandi; which give me a true grasp of his strengths and weaknesses. Even sensitive scholars relying on instinct cannot rival this knowledge. The fact that my findings are entirely in accord with the documents of his contemporaries and near contemporaries; must add considerably to their credibility. My findings are completely at odds with today's “experts”. In his introduction to the Dover edition of the “Drawings of Rembrandt” and his School, Prof. Slive sites the near unanimity as reason for giving extra credence to scholarly opinion. I would argue, on the contrary, that it demonstrates the hopelessly hierarchical system of promotion within the discipline of art history: a structure that systematically eliminates any heresy. [My own experience as a rising star that was subverted by the unanimous voice of the Rembrandt “experts” I need not repeat here. Suffice it to say that without the democratizing influence of internet my voice would have been effectively silenced. The other media have not given me space for over 25 years though my discovery was once hailed as “The Rembrandt Revelation” by The Observer. Apparently the “experts” can successfully defend the indefensible by drowning my solid evidence with the sheer volume of their babble. The present volume is a striking example of this phenomenon.] Criticism of The Biblical Subjects I limit myself to the Biblical Subjects because that is where my evidence is grounded. This catalogue breaks with normal precedent by not making it clear just how far it strays from earlier scholarly opinion. It strays very far indeed. Over 20 of the drawings here attributed to pupils were accepted by Otto Benesch in 1954. In not one single case can the student suggested by these authors be shown to have even a hint of Rembrandt's characteristic gifts, nor for that matter, his weaknesses. I will attempt to define these as we look at the examples.Example 1. A drawing of Lot and his family being led out of Sodom by an Angel, was accepted as a Rembrandt by Benesch, B.129 in his 1954 catalogue. It has been re-attributed to one Jan Victors, of whom few people will ever have heard, nor is there any proof that he was ever a student of Rembrandt's. His paintings are undoubtedly Rembrandt inspired in colour and tone but his idea of form is much more classical than Rembrandt's. The two Victors drawings reproduced in the catalogue to back the re-attribution have nothing in common with this, other than the use of brown ink as a medium. They are feeble by any standard. This (B.129) on the other hand is characteristic of Rembrandt in two important respects: Lot himself is typical of Rembrandt when drawing from life – the clasped hands are an oft recurring item – the head is typical, particularly in the modification of the line of the forehead, which turns Lot slightly in our direction so he does not present us with a pure profile.B.129 Lot being led out of Sodom by an angel

His stance is suitably expressive of discomfort, his cloak recognisable from Rembrandt's theatrical wardrobe. But most characteristic of Rembrandt are the accompanying figures behind Lot. They are not observed from life but invented and therefore “ worthless in his (Rembrandt's) eyes”. I know of no other artist but Rembrandt who would be prepared to demonstrate just how worthless he is “without life in front of him”. For me the pose of the leading angel is of a different and superior order, he probably has been sketched from life. The very different quality of these figures make it certain that Benesch was right and the present authors, dangerously misleading.B.129 Lot's face

Example 2. A mother suckling a baby B.359 is one of Rembrandt's most lovely drawings. If anyone can accept that Bol might possibly have drawn the “Hagar and the Angel” the subject matter of my film then of course there is no reason why Bol should not have drawn many of Rembrandt's greatest successes, however, the quality of his real drawingB.359 Mother Suckling a baby

and the pathetic quality of his painted Hagar make this quite impossible. Bol's box of drawings in the Rijksmuseum does, alas, contain many of Rembrandt's most precious pearls.Bol: Hagar and the Angel

Example 3. also now attributed to Bol once B.537, of Christ mistaken for a gardener, is another splendid example of the way Rembrandt can catch, with a few well selected directions of limbs and perfect sense of balance, a most relaxed pose. Vintage Rembrandt, an unerring sense of space.b.537 Jesus mistaken for a gardener

Example 4. of Esau selling his birthright to Jacob for a bowel of potage, B.564 could hardly be more typical of Rembrandt, particularly as the second superfluous bowel suggest that the drawing is loosely based on a mirror image.B.564 Esau sells his birthright

B.121 An actor being crowned. Now attributed to Flinck

Examples 5 & 6 B.121 & B.122 are infinitely closer to Rembrandt's many drawings of actors than to anything known from Flinck or Eeckout to whom they are now re-attributed. This madness must be stopped! I could go on and on but this is probably enough for now.B.122 a Bishop: attributed to Eeckout

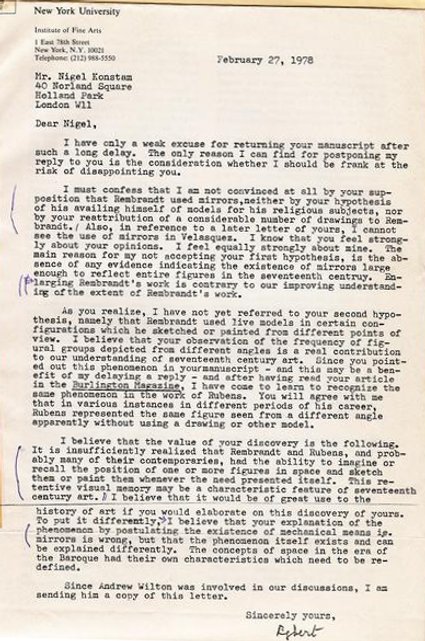

See transcript below for ease of reading.

New York Univerersity

Institute of Fine Arts

1 East 78th Street

New York

N.Y.10075

Mr Nigel Konstam

40 Norland Square

Holland Park

London W11

February 27, 1978

Dear Nigel,

I have only a weak excuse for returning your manuscript after such a long delay. The only reason I can find for postponing my reply to you is the consideration whether I should be frank at the risk of disappointing you.

I must confess that I am not convinced at all by your supposition that Rembrandt used mirrors, neither by your hypothesis of his availing himself of models for his religious subjects, nor by your re-attribution of a considerable number of drawings to Rembrandt. Also, in reference to a later letter of yours, I cannot see the use of mirrors in Velasquez. I know that you feel strongly about your opinions. I feel equally strongly about mine. The main reason for my not accepting your first hypothesis, is the absence of any evidence indicating the existence of mirrors large enough to reflect entire figures in the seventeenth century. Enlarging Rembrandt’s work is contrary to our improving understanding of the extent of Rembrandt’s work.

As you realize, I have not yet referred to your second hypothesis, namely that Rembrandt used live models in certain configurations which he sketched or painted from different points of view. I believe that your observation of the frequency of figural groups depicted from different angles is a real contribution to our understanding of seventeenth century art. Since you pointed out this phenomenon in your manuscript – and this may be a benefit of my delaying a reply – and after having read your article in the Burlington Magazine, I have come to learn to recognize the same phenomenon in the work of Rubens. You will agree with me that in various instances in different periods of his career, Rubens represented the same figure seen from a different angles apparently without using a drawing or other model.

I believe that the value of your discovery is the following. It is insufficiently realized that Rembrandt and Rubens, and probably many of their contemporaries, had the ability to imagine or recall the position of one or more figures in space and sketch them or paint them whenever the need presented iself. This retentive visual memory may be a charcteristic feature of seventeenth century art. I believe that it would be of great use to the history of art if you would elaborate on this discovery of yours. To put it differently. I believe that your explanation of the phenomenon by postulating the existence of mechanical means in mirrors is wrong, but that the phenomenon itself exists and can be explained differently, the concepts of space in the era of the Baroque had their own characteristics which need to be redefined.

Since Andrew Wilton was involved in our discussions, I am sending him a copy of this letter.

Sincerely yours,

Egbert

There was an exhibition at The Rembrandthuis at the turn of the year 84/85 that gave ample reason to fear the madness that has now been carried through with a vengeance at the Getty. Nonetheless the devastation of Rembrandt’s portfolio has left me dumbfounded. The level of corporate madness is beyond belief, The Director of the Getty welcomes this volume, “Drawings by Rembrandt and his Pupils, telling the difference” as ’stunning and momentous’ I agree but not in the sense that Michael Brand probably intends.

Anyone who approaches this enormous volume in the hope of understanding what distinguishes the greatest master from his pupils will be sorely disappointed. In the majority of cases there is no difference because the specimens held up as by pupils are the result of recent re-attribution and are clearly by Rembrandt himself. As a result we see the master as surrounded by little known nonentities who could, when they felt like it, turnout masterpieces which had fooled generations of experts but not apparently Mr. Schatborn and his colleagues. The arrogance takes one’s breath away.

Rembrandt scholarship of the last 50 years has been an escalating disaster, Benesch’s catalogue of 1954, which I would wish to enlarge has been reduced by approximately 50% and the resulting bonanza of master drawings handed out indiscriminately to obviously unworthy students. Indeed, in some cases they cannot even be shown to have been students. The idea that anyone has the ability to suddenly turn out a drawing that has passed for a Rembrandt because of its penmanship and sharpness of observation and then chosen to revert back to their middling talent is just too absurd. This catastrophe can only have resulted from the inbreeding of Rembrandt scholarship. No new blood or ideas are allowed to enter. The Rembrandt Mafia have hermetically sealed themselves from the intrusion of advice from the practitioners.

No draughtsman could possibly go along with the recent misjudgments, where some of Rembrandt’s finest drawings have been handed out to mediocrities or, in the case of Carel Fabritius, to a fine painter who had not previously shown a talent for drawing. There is no evidence whatever that these scholars have the least idea of what makes a great drawing (see www.saveRembrandt.org.uk for details).

Some of the reproductions in this lavishly produced volume are so small as to preclude the necessary comparisons. Common sense forces me to believe that scholarship since my article in “The Burlington Magazine” February 1977 is not only misguided but verging on fraudulent. Anyone contemplating a libel action on the strength of this statement should study that article and the letter from Prof. E.Haverkamp Begerman which conveniently summarizes the false assumptions on which Rembrandt scholars have continued to destroy Rembrandt in the face of my own evidence and the unanimous voice of Rembrandt’s contemporaries.

The crucial points are

1.Rembrandt “would not attempt a single brush-stroke without a living model before his eyes”(Houbraken). Or, “Our great Rembrandt was of the same opinion that one should follow only nature, anything else was worthless in his eyes.” (Karel van Mander as reported by Houbraken) and there are many more quotes of the same character. The scholars would have us believe exactly the opposite: that Rembrandt actually taught his students to invent, not to observe.

-

The evidence in My article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” proves, beyond reasonable doubt, that these statements are remarkably accurate. The proof of groups of live models in Rembrandt’s studio for the Biblical and other group subjects is incontestable. My recent film on Youtube “Rembrandt’s Adoration of the Shepherds” makes the same point on a grand scale. There we see practically the entire subject matter of two paintings (one seen direct and the other observed from Rembrandt’s same position but reflected in an angled sheet of polished pewter, accurately recorded by Rembrandt even to the extent that the more impressionistic technique suggests the blurred quality of the image reflected in polished metal. Both paintings were once accepted as by Rembrandt). The chances of these very complex space relationships happening by chance, or being constructed by calculation must be millions to one against. There are just too many reversals seen from a different point of view. To suggest, as Prof. E.Van der Wetering does that these were typical exercises in Rembrandt’s atelier is unacceptable lunacy.

This evidence which cuts the ground from under the scholars view is not mentioned let alone discussed in the Getty catalogue. For instance in the penultimate and last paragraph p19-20 explain how Rembrandt’s etching of “The Dismissal of Hagar”1637 “made a great impression on his pupils and inspired many variants….we do not know precisely how drawing from the imagination was handled in Rembrandt’s atelier…..” Yet I, Konstam, have explained precisely how Rembrandt himself developed eleven variants of the same subject from the group of three live models posed in his studio; observing sometimes direct, and sometimes in a mirror to their left and at other times in a mirror behind them, but always from the same seat in his studio. The DVD is available on www.saveRembrandt.org.uk also in the Arts Review Yearbook 1989, not to mention my unpublished book; freely circulated among the Rembrandt establishment many years before.

Peter Schatborn who master-minded the catalogue of The Rembrandthuis exhibition from his position in charge of the prints and drawings at the Rijksmuseum, was also the major contributor of the exhibition at The Getty. He can hardly claim ignorance of my discoveries as he translated my second article into Dutch for inclusion in The Rembrandthuiskroniek in 1978.

The fact is that today’s art theorists seem to have no understanding of the importance of observation in human affairs. It is not enough that scientists are so good at it, their observations are specialized; artistic observation is also specialized but specialized in a different area, an area where neglect is already horrifyingly apparent. By destroying Rembrandt, the figurehead of observed art, the theorists have slued modern art with such success we have to doubt whether it can ever recover. First we must recover The Greater Rembrandt by putting an end to Rembrandt scholarship as it now exists.

Do not burn their books, preserve them as a warning to future generations of experts.

Surprisingly it is necessary to learn to observe. Observation is a specialized activity and each of us has a mind that more easily absorbs either visual or auditory (language based) experience. I, for instance, could not tell you the names of streets that I pass every day because I find my way visually, the street names are irrelevant to me. If one is going to become a specialist in art it is important to start with the right “visual” mental make-up.

The present system of selecting art historians seems more concerned with their auditory ability: to learn languages, rather than to observe art. This selection process means students spend their time reading the literature rather than quizzing the works of art. Art History desperately needs practical revision; embroidering on the literature inevitably leads to the accumulation of myth.

The selection of students is a fundamental mistake that has led us into the present morass: the blind leading the “visual” astray. As George Orwell wisely noted “He who controls the present controls the past.” Rembrandt is being changed beyond recognition by those who control Art History today. It is very rare for an artist to get published in an Art History Journal; rarer still for an artist’s findings to be assimilated by the professionals, we are poles apart. It is only in the last 50 years that art historians have been allowed to dictate the direction of art; it has been a disaster.

This web site proves, beyond reasonable doubt, that Rembrandt worked by observation and not by his ability to invent. This is a fundamental aspect of his artistic make-up. In the case of “The Adoration of the Shepherds” we have two paintings, which replicate on a grand scale, what I have been saying about Rembrandt’s practice in drawings since 1974. It would need an astronomer’s mathematics to work out the odds of such a thing happening by any other means than the use of a mirror. I can only guess it must be many millions to one, against. The reversal of a new point of view of a very complex visual array, can be achieved naturally with an angled mirror. To do it by calculation, as the RRP suggests in this case, is virtually impossible. This being so, it is clearly absurd to go on training young minds to see Rembrandt according to the ideas of the Rembrandt establishment, which deny Rembrandt’s reliance on observation and indeed would have us believe that he taught his students to invent! This is a reversal of all documentary evidence as well as the evidence manifest in his works. It must not be allowed to continue.

There are a simple explanations for Rembrandt’s variability. I have tried to make Rembrandt scholars see this since 1977 through publications, lectures and this web site. Yet, I have not succeeded in attracting a single art historian to my courses; they are hermetically sealed from criticism. Artists accept my version of Rembrandt but alas, are too preoccupied with their own work to take the necessary action.

The main lines along which to come to an understanding of Rembrandt are set out here link but I know that they will not suffice on their own. A minimum of three months practical work is necessary to re-educate, even a “visual”mind. It is frustrating to think the breakthrough I have made in understanding is to be lost if I can find no one interested in continuing the battle to return Rembrandt to his rightful, supremely respected place in the history of painting and drawing. Our visual culture is in a state of collapse. At the age of 77 it is obvious that I will not be able to instruct the young for the indefinite future.

The insights gained from such a course will prove useful beyond Rembrandt studies. An appreciation of Rembrandt is a study of the greatest, most advanced artist in the field of human behaviour. Have our present “experts” contributed one iota to that study? They continue with their study of style which was rendered obsolete when it was discovered that Rembrandt responded variously to the varying stimuli: life, reflection and in the case of imaginative construction, the lack of stimulus. The variety had little or nothing to do with his maturity, everything to do with the quality of the stimulus. For instance, the style of his late etched nudes is remarkably similar to his early etched nudes. Any attempt to assign dates to Rembrandt’s drawings by style is empty posturing; the recent re-attributions are outrageous nonsense. Rembrandt studies at present are worse than a waste of time: they are deeply misleading and have damaged his reputation unjustly.

*******************************

The words Art History have a rather conservative ring to them, which is deceptive. The contrary is true. Art historians have fostered a culture of “the new” quite regardless of whether the new ideas produce greater awareness or less. The sad truth is that we have in the last 50 years regressed very considerably in awareness. The story of recent Rembrandt scholarship where literally hundreds if not thousands of academics have clung to a doctrine that the facts and the documents deny, is proof enough that our visual culture is in steep decline.

Art historians concerns are not the concerns of trained artists. They cling to a very narrow view of style which makes no real sense in quality evaluation. I was trained in art schools before 1960. The criticism of drawing took the form of assessing the mass; the form, usually of nude human beings, how they were perceived in light and how they resisted gravity. The style of handwriting was not considered worthy of comment. One hundred years earlier the criticism would probably also have included questions about what the pose actually meant in terms of drama, character or feeling.

Such humanist questions were estewed in the 1950s as too literary, not architectural enough for “real art”. We were under the influence of Roger Fry , with his “pure form” as being the only proper concern of the true artist. Rembrandt, if he could have understood this concept at all, would hardly have concurred. The fact is that modern criticism can no longer deal with Rembrandt’s primary concerns as an artist. The more rigorously modern the critic the less chance there is of awareness of human expression. Our focus has narrowed alarmingly; a changed for the worse, that is clearly reflected in our everyday life. We need to put Rembrandt back where he belongs – at the top; for our own well-being.

I still await an answer to this letter

Nigel Konstam (director)

CENTRO D’ARTE VERROCCHIO

Via San Michele 16,

Casole d’Elsa, 53031, SI, Italy.

tel 0039-0577-948312 fax –399

to The Director of The National Gallery (London)

July 18th 2010

Dear Dr. Penny,

I am writing to draw your attention to an anomaly that needs to be cleared up surrounding the Rembrandt painting “The Adoration of the Shepherds” in The National Galleries collection. Once vetted by your scientific staff and accepted as genuine, now on show in your current exhibition of “Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries” where it is attributed to an unknown advanced student of Rembrandt’s.

I am aware that the RRP have found it wanting but I have proved, quite beyond reasonable doubt, that it is painted from the same group that Rembrandt set up in a barn for his accepted painting of the same subject in Munich. It is observed from the same viewpoint as he used for the Munich painting but viewed through a large mirror; probably made of polished pewter or copper (the copper giving a more Rembrandtesque warmth to the image).

This procedure may seem an odd thing for him to have done but I have shown in my article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” (Burlington Feb ‘77) that this was a normal practice for him; when drawing. In fact, he used it nearly 100 times for drawings. This is the only time it can be proved in painting. When I say ‘proved’ the precise relationship between the two subjects, not only in the number of objects reflected but also the spaces between them remains constant, this precludes any other explanation. If you can imagine the task of reversing a complex three dimensional array and seeing it from a different point of view; you will immediately see that Prof Van der Wetering’s explanation as a student exercise, vastly underestimates the complexity of the interrelationships.

We could suggest that a student took over Rembrandt’s place but there is no student capable of such nearness to Rembrandt’s style, hence his“anonymity”. The much more impressionistic treatment of the subject is due to Rembrandt’s reaction to a less clear image in the reflector. This change of quality is also obvious in the drawings. See for example the comparison between the two versions of Isaac Blessing Jacob B1065 & B891 in my article. Both were drawn from the same group of models under identical lighting; yet B1065 drawn from the reflection is vaguer in treatment. Just what we find in the National Gallery’s version of The Adoration!

Though I live in Tuscany I would be pleased to come to London to give a talk or take part in a debate to clear up this rather crucial divergence of opinion. I enclose a DVD which shows I have plenty to say on the subject. The 5 min film on the Adorations is in the last chapter of the DVD or on Youtube. My saveRembrandt website (as above) with a blog on the Verrocchio site. You will find that my view of Rembrandt agrees with that of his contemporaries “He would not attempt a single brush-stroke without a living model before him, anything else was worthless in his eyes”, where the official view is that he actually taught his students to invent! Rembrandt was an observer not an inventor, this case of the Adorations proves that most forcefully.

Yours sincerely,

Nigel Konstam