Venus and Cupid - Bronzino

I have known and admired Bronzino’s masterpiece in the National Gallery, “The Allegory of Venus and Cupid” all my life. The newly opened exhibition at the Strozzi Palace in Florence of Bronzino’s life’s work (80% of his paintings) is very exciting. It allows one to see him in context, by comparisons with his mentor and friend, Pontormo and contemporary Cellini. (The National Gallery painting is one of the few important works not on show here.)

The range of his work is amazing. His portraits vary in quality, I would guess; according to the number of sittings he was able to exact. The faces of the children of Cosimo I are somewhat doll-like but their costumes are painted with the most consummate ‘trompe l’oeil’ skill. This is true of many of his paintings. His attention to detail is breathe-taking. His best hands can compare with the greatest. When you add to this the beauty of his colour, the gorgeous rhythmic texture of his low-relief type subjects, his mastery of mannerist composition generally, the near VanEyk quality of his best portraits – the word ‘genius’ must spring to mind. The sensuality, range and sensitivity shines through the Mannerism.

There is a newly attributed Crucifixion which extends the range of his painting still further. The extreme austerity of the treatment of this much used subject, holds one spellbound. Little wonder it has evaded recognition for so long. It is not typical, yet this most varied painter is surely it’s author.

There is a small book “Bronzino Revealed” which contains a conversation between the experts which helps one to understand the cultural context in which he worked. It whets one’s appetite for his poetry but without sufficient examples. Nor does it divulge the secret of the new varnishing treatment that allows one to appreciate the consummate skill of the painter even though the varnish is so reflective that at times one seems to be looking through glass.

The museum is devoted to the history of the making of art. The museum’s collection has accumulated over the last forty years as a result of stumbling on the unexpected . When I see something inconsistent with my experience – I seek to explain the inconsistency. This has led to a sequence of art discoveries which could bring about a new understanding of art.

Artists understandably keep secrets about their methods to maintain an advantage over rivals within their profession. Centuries later their secrets often remain hidden. This may happen because of our desire for super-heroes – we want to believe in the magical. This museum is about delving into the truth about how things were made, based on the artefacts themselves, questioning the art mythology.

We have concrete evidence that the Classical Greek sculptors did not follow the “proper” art school procedure of observing from a life-model but used a hollow wax cast taken from life. This came as a great shock. It has upset our sense of where we come from. It requires the revision of Art History. By following the clues present in all the life-size bronzes that survive from the Severe and Classical periods we are led to a very different conception to the one we have accepted for the last 2500 years.

Long ago Pliny reported that life-casting was invented by Lysistratus around 350BC but few historians have acknowledged this possibility. In fact my discovery pushes that date back to around 500BC; the moment when the great Greek revolution changed the course of history with the discovery of natural movement: the famous Greek contraposto. We must now see this leap forward, more as a technical advance, rather than a leap of the imagination. Up to that time the Greeks had followed the Egyptian pattern but less successfully than the Egyptians. Their revolution all happened too quickly, in less than 50 years. Nonetheless my concrete evidence, like Pliny’s report, is neglected.

*****

My most important discovery is Rembrandt’s need to have life in front of him when drawing or painting. In the museum we will see that Rembrandt was a different and inferior artist if he didn’t work from life. Rembrandt’s genius is based on his observation of human interaction: body language, which he conveys through his precise observation of space relationships, usually set up in his studio with live models and theatrical properties.

The importance of his use of mirrors is that it shows us definitively how Rembrandt worked . The experts’ ideas about the development of his style are wrong. The relationship between Rembrandt and his students are also gravely misleading.

Though he could not work out of his head, Rembrandt’s imagination was more serious than is commonly meant by the term. Coleridge, a poet who thought very deeply about imagination, distinguished between “fancy”(fantasy) and true imagination. The brain receives the world through the senses but we all need imagination to make sense of these perceptions. Rembrandt made new and better sense of what he saw, psychologically, using his genuine interpretive imagination. If our experts could take Rembrandt’s and Coleridge’s lessons to heart the future course of art and criticism would be of much greater value to us.

Rembrandt is clearly the most evolved artist that has ever existed. Yet we have witnessed a steep decline in his perceived stature because the art historians refuse to revise their time honoured misunderstandings. They rely too unquestioningly on the literature of art, (including the artists’ own self-promotions) and seem unable to interpret the primary evidence, the artefacts.

The subjects covered in the museum are in chronological order :-

GREECE

1. The discovery that the Greeks used life-casting for their life-size figures from the time of Phidias onwards.

2. a chimney on the Acropolis in Athens, and another in Olympia.

3. a method of steaming moulds to recover 70% of the wax usually lost, used at Rhodes and almost certainly elsewhere.

ROME

Roman geometry had an enormous influence on subsequent art that is seldom acknowledged. The analysis of a portrait bust of Hadrian in the British Museum, demonstrates this geometry. Those artists who have used it since are also represented.(Mantegna, Holbein, Rembrandt, Degas, Giacometti)

SIENA

1. An appreciation of the works of Rinaldo da Siena recently discovered under the cathedral.

2. Reasons why the so called “Duccio Window” cannot be by Duccio.

3. The discovery of the dimension of time in Simone Martini’s Madonna of the Annunciation.

FLORENCE

1. The probable use of a polished silver mirror in Brunelleschi’s second essay in perspective.

2. The probable use of sculptural maquettes in conjunction with mirrors by Masaccio.

3. Michelangelo’s use of maquettes for preparatory drawings

4. Cellini’s casting method is demonstrated to be very close to the method of Phidias.

REMBRANDT’S use of live models and mirrors, indicating that his contemporaries knew a Rembrandt that modern scholarship has all but destroyed; an artist whose example is very important to artists who observe life today.

VELASQUEZ’ use of a large mirror from the Hall of Mirrors at the Royal Palace in Toledo for the composition and rapid completion of his most important masterpiece – “Las Meninas”.

VERMEER’S use of two mirrors in conjunction with a camera-oscura as an aid for painting.

———————–

If there were space available in some future museum. I would like to include some of David Hockney’s discoveries as presented in his fim and book “Secret Knowledge”. He is another artist who has made a very considerable contribution to the true history of Art. I found his suggestions about the use of the concave mirror very convincing and also his demonstration of Caravaggio’s methods. In the museum you will see that I have something to add to his ideas about Brunelleschi, Velasquez and Vermeer. What he had to say about Flemish, as opposed to Florentine perspective, I found positively illuminating. Perhaps it could only be explained so well by an artist such as Hockney, who uses photo-collage.

Nigel Konstam

February 2008

Rembrandt is universally regarded as among the great seers of humanity:

a creative genius. It is worth inquiring how he achieved this

pre-eminence. Unlike his chosen artistic partner Lievens, he was not a

child prodigy. In fact, his early works give no inkling of the genius he

was to become. It is not easy to decide who was the major influence on

his development Lievens or Lastman. Lastman was the master in whose

atelier Rembrandt and Lievens met as students.

I tend to favour Lievens; as Rembrandt’s very short stay with Lastman (6

months) suggests antagonism of some kind. Rembrandt made numerous copies

of Lastman’s work. Perhaps these copies were a compulsory but resented

part of the Lastman teaching. Rembrandt’s copies of Lastman are also

criticisms. On the other hand he learnt rapidly and uncritically from

Lievens. His early Leyden works are very strongly influenced by Lievens.

Rembrandt and Lievens worked together from nature, perhaps this was the

crucial difference between the methods of teaching and speed of

assimilation. If this is so Rembrandt had learnt the prime lesson of the

great leap forward in science. Observing nature directly was the secret

of that success. Furthermore, the documents of Rembrandt’s life give

incontrovertible support to the idea that working from nature was

crucial “anything else was worthless in his eyes”. It is difficult to

see how scholarship came to the opposite conclusion: that Rembrandt

imagined his Biblical pieces. Even today scholars remain convinced of

that idea. Perhaps I should attempt to explain their strange behaviour.

[There are two aspects of recent scholarship that are entirely

undermined by my re-discoveries:

1. the dating of drawings by style is no longer tenable. The changes

in style are demonstrated to be the result of either different

media or different stimuli: reality, reflection or imagined.

2. the vast literature on the iconography of Rembrandt and his school

becomes a laughing-stock. All that speculation about the shifts in

emphasis found in the student works are explained by the differing

view point of the physical groups of models in Rembrandt's studio.

These are not mere peccadilloes that can be lightly laughed off. The

scholars are used to being taken seriously, they are entrusted with our

artistic patrimony. These two major gaffs undermine their status as

experts.]

**************************

An unusual characteristic of Rembrandt’s behaviour is his acceptance of

failure as the possible outcome of an experiment. He did not tidy away

his failures as others did. If you accept the greater, more prolific

Rembrandt that I propose, it could be said, he advertised his failure to

draw from the imagination. I interpret this “carelessness” as a

wonderful openness and generosity. He seemed to want us to know how he

had arrived at the summit; perhaps, he did this so that we could emulate

his behaviour and push further with his insights into the working of the

psyche in the physical world.

Rembrandt earned a reputation for leaving his work unfinished but was

unconcerned. Furthermore, only about twenty drawings can be identified

by signature or handwriting, the rest we have to chose according to our

understanding of his aims and style of thought. Rembrandt’s confidence

in his own unique character as an artist was justified. The sensibility

of our “experts” is the issue. For instance ex. 7 & 8 are both typical

of Rembrandt’s concerns and his habits as an artist. The little dog in

Ex.9 is a veritable Rembrandt trademark! He loved dogs and could

obviously draw them from memory, unlike his angels.

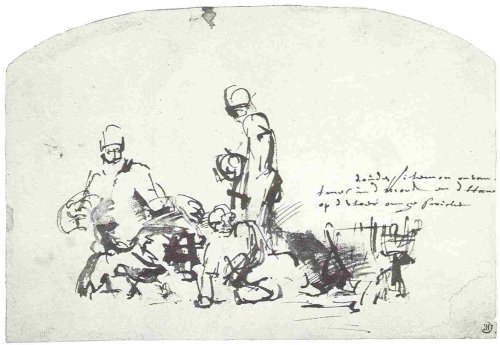

Example 7

No.7 has been re-attributed to Drost, in spite of the fact that

Rembrandt did an etching of precisely this subject. The treatment of the

clasped hands of Tobias could hardly be closer to the hands of his

mother in the drawing still accepted as a Rembrandt; reproduced in the

catalog opposite for contrast. The angel has that clumsy feel of

Rembrandt constructing from imagination rather than observing. All the

other figures express shock as we would expect from Rembrandt.

Example 8

Ex.8 is re-attributed to an unidentified student of Rembrandt. We are

therefore unable to compare with known examples. We can be certain that

the central group would be much closer to the Rembrandt on the opposite

page. In fact, the “mocker” is so typical of Rembrandt and better

realized here, than in the accepted drawing. If I was going to talk of

the style of this figure I would be referring to it’s compactness, its

sculptural quality, it’s balance, it’s geometry and it’s expressive

quality. The handwriting is of no importance to it’s quality as art. If

we talk about the style of Dickens we are looking at his entire

philosophy, his use of words, not his handwriting! Why can we not get

Scotland Yard onto these drawings to compare inks, pens etc. they would

make a far better job. Our experts are to be pitied, not to be listened to.

Fortunately, Rembrandt signed and dated his etching plates. Therefore

the etchings and paintings give us a fairly reliable foundation on which

to build. They give me the feeling of a man so absorbed in his journey

that he will sacrifice whatever is necessary in craftsmanship,

draughtsmanship or detail to keep up the momentum. “A picture is

finished when the painter feels he has expressed his intention in

it.”(Rembrandt as reported by Houbraken). What an excellent example for

us all: this is why his intentions are so obvious to some of us. His

drawings should be seen as steps towards finding his intention: that is

his interpretation of the Bible story. Ex.1.expresses a particular

relationship between Lot and the Angel, this is Rembrandt at work with

his practical brand of imagination: sodomy is a male concern, forget the

pillar of salt.

There are many important lessons we can learn from Rembrandt:-

One, is not to be frightened of failure, we need to learn to acknowledge

our failures and then learn from them.

A second lesson is to learn to feed one’s imagination. Rembrandt did

this by producing model groups in his studio; the closest he could get

to the actual occurrence (the Bible story). This was a part of his art.

His unique success in depicting human relationships lies in the physical

“production” of the re-enactment. “He would spend a day or even two

adjusting the folds of a turban until he was satisfied”. We can presume

that he spent equal time arranging his actors.

Third, was his drawing strategy: he put top priority on the disposition

of the masses in space. This is how the physical pose expresses the

spirit of his protagonists so brilliantly. Perhaps, this can be

appreciated more fully by those who practice drawing or acting

themselves. The scholars’ study of style amounts to no more than the

study of the idiosyncrasies of his handwriting, which they have then

misinterpreted and over played.

The scholars’ search for “ the leaner, fitter Rembrandt” has pruned away

most of these valuable lessons for artists. We must learn to see

Rembrandt’s drawings as he himself saw them: as journeys of discovery,

which only occasionally end with the hoped for, pot of gold.

Surprisingly, Rembrandt did not sign the jewels, he signed his gifts in

autograph albums etc. which were often from imagination

Example 9 Homer

and therefore mediocre. He unwisely left it to the taste of the connoisseurs

to recognise his true hand. He even left proof of authorship on his

least satisfactory products.

Ex.10, B.960 Jupiter with Philemon and Baucis, an illuminating inability. Rembrandt has had to write the story that the drawing fails to tell.

The museum“experts” tend to see the drawings as valuable items in a

collection, and their job as to weed out the duds. I hope I have shown

sufficient reason why we do not want that weeding to continue; we lose

much too much in the process. Tragically today’s scholars are not good

at weeding. Through their pruning over the last 100 years we have lost

sight of many of Rembrandt’s greatest drawings . Their confidence swells

as the great Rembrandt shrinks; they must be stopped!

My experiments with maquettes and mirrors have given me a fresh insight into Rembrandt's modus operandi; which give me a true grasp of his strengths and weaknesses. Even sensitive scholars relying on instinct cannot rival this knowledge. The fact that my findings are entirely in accord with the documents of his contemporaries and near contemporaries; must add considerably to their credibility. My findings are completely at odds with today's “experts”. In his introduction to the Dover edition of the “Drawings of Rembrandt” and his School, Prof. Slive sites the near unanimity as reason for giving extra credence to scholarly opinion. I would argue, on the contrary, that it demonstrates the hopelessly hierarchical system of promotion within the discipline of art history: a structure that systematically eliminates any heresy. [My own experience as a rising star that was subverted by the unanimous voice of the Rembrandt “experts” I need not repeat here. Suffice it to say that without the democratizing influence of internet my voice would have been effectively silenced. The other media have not given me space for over 25 years though my discovery was once hailed as “The Rembrandt Revelation” by The Observer. Apparently the “experts” can successfully defend the indefensible by drowning my solid evidence with the sheer volume of their babble. The present volume is a striking example of this phenomenon.] Criticism of The Biblical Subjects I limit myself to the Biblical Subjects because that is where my evidence is grounded. This catalogue breaks with normal precedent by not making it clear just how far it strays from earlier scholarly opinion. It strays very far indeed. Over 20 of the drawings here attributed to pupils were accepted by Otto Benesch in 1954. In not one single case can the student suggested by these authors be shown to have even a hint of Rembrandt's characteristic gifts, nor for that matter, his weaknesses. I will attempt to define these as we look at the examples.Example 1. A drawing of Lot and his family being led out of Sodom by an Angel, was accepted as a Rembrandt by Benesch, B.129 in his 1954 catalogue. It has been re-attributed to one Jan Victors, of whom few people will ever have heard, nor is there any proof that he was ever a student of Rembrandt's. His paintings are undoubtedly Rembrandt inspired in colour and tone but his idea of form is much more classical than Rembrandt's. The two Victors drawings reproduced in the catalogue to back the re-attribution have nothing in common with this, other than the use of brown ink as a medium. They are feeble by any standard. This (B.129) on the other hand is characteristic of Rembrandt in two important respects: Lot himself is typical of Rembrandt when drawing from life – the clasped hands are an oft recurring item – the head is typical, particularly in the modification of the line of the forehead, which turns Lot slightly in our direction so he does not present us with a pure profile.B.129 Lot being led out of Sodom by an angel

His stance is suitably expressive of discomfort, his cloak recognisable from Rembrandt's theatrical wardrobe. But most characteristic of Rembrandt are the accompanying figures behind Lot. They are not observed from life but invented and therefore “ worthless in his (Rembrandt's) eyes”. I know of no other artist but Rembrandt who would be prepared to demonstrate just how worthless he is “without life in front of him”. For me the pose of the leading angel is of a different and superior order, he probably has been sketched from life. The very different quality of these figures make it certain that Benesch was right and the present authors, dangerously misleading.B.129 Lot's face

Example 2. A mother suckling a baby B.359 is one of Rembrandt's most lovely drawings. If anyone can accept that Bol might possibly have drawn the “Hagar and the Angel” the subject matter of my film then of course there is no reason why Bol should not have drawn many of Rembrandt's greatest successes, however, the quality of his real drawingB.359 Mother Suckling a baby

and the pathetic quality of his painted Hagar make this quite impossible. Bol's box of drawings in the Rijksmuseum does, alas, contain many of Rembrandt's most precious pearls.Bol: Hagar and the Angel

Example 3. also now attributed to Bol once B.537, of Christ mistaken for a gardener, is another splendid example of the way Rembrandt can catch, with a few well selected directions of limbs and perfect sense of balance, a most relaxed pose. Vintage Rembrandt, an unerring sense of space.b.537 Jesus mistaken for a gardener

Example 4. of Esau selling his birthright to Jacob for a bowel of potage, B.564 could hardly be more typical of Rembrandt, particularly as the second superfluous bowel suggest that the drawing is loosely based on a mirror image.B.564 Esau sells his birthright

B.121 An actor being crowned. Now attributed to Flinck

Examples 5 & 6 B.121 & B.122 are infinitely closer to Rembrandt's many drawings of actors than to anything known from Flinck or Eeckout to whom they are now re-attributed. This madness must be stopped! I could go on and on but this is probably enough for now.B.122 a Bishop: attributed to Eeckout

There was an exhibition at The Rembrandthuis at the turn of the year 84/85 that gave ample reason to fear the madness that has now been carried through with a vengeance at the Getty. Nonetheless the devastation of Rembrandt’s portfolio has left me dumbfounded. The level of corporate madness is beyond belief, The Director of the Getty welcomes this volume, “Drawings by Rembrandt and his Pupils, telling the difference” as ’stunning and momentous’ I agree but not in the sense that Michael Brand probably intends.

Anyone who approaches this enormous volume in the hope of understanding what distinguishes the greatest master from his pupils will be sorely disappointed. In the majority of cases there is no difference because the specimens held up as by pupils are the result of recent re-attribution and are clearly by Rembrandt himself. As a result we see the master as surrounded by little known nonentities who could, when they felt like it, turnout masterpieces which had fooled generations of experts but not apparently Mr. Schatborn and his colleagues. The arrogance takes one’s breath away.

Rembrandt scholarship of the last 50 years has been an escalating disaster, Benesch’s catalogue of 1954, which I would wish to enlarge has been reduced by approximately 50% and the resulting bonanza of master drawings handed out indiscriminately to obviously unworthy students. Indeed, in some cases they cannot even be shown to have been students. The idea that anyone has the ability to suddenly turn out a drawing that has passed for a Rembrandt because of its penmanship and sharpness of observation and then chosen to revert back to their middling talent is just too absurd. This catastrophe can only have resulted from the inbreeding of Rembrandt scholarship. No new blood or ideas are allowed to enter. The Rembrandt Mafia have hermetically sealed themselves from the intrusion of advice from the practitioners.

No draughtsman could possibly go along with the recent misjudgments, where some of Rembrandt’s finest drawings have been handed out to mediocrities or, in the case of Carel Fabritius, to a fine painter who had not previously shown a talent for drawing. There is no evidence whatever that these scholars have the least idea of what makes a great drawing (see www.saveRembrandt.org.uk for details).

Some of the reproductions in this lavishly produced volume are so small as to preclude the necessary comparisons. Common sense forces me to believe that scholarship since my article in “The Burlington Magazine” February 1977 is not only misguided but verging on fraudulent. Anyone contemplating a libel action on the strength of this statement should study that article and the letter from Prof. E.Haverkamp Begerman which conveniently summarizes the false assumptions on which Rembrandt scholars have continued to destroy Rembrandt in the face of my own evidence and the unanimous voice of Rembrandt’s contemporaries.

The crucial points are

1.Rembrandt “would not attempt a single brush-stroke without a living model before his eyes”(Houbraken). Or, “Our great Rembrandt was of the same opinion that one should follow only nature, anything else was worthless in his eyes.” (Karel van Mander as reported by Houbraken) and there are many more quotes of the same character. The scholars would have us believe exactly the opposite: that Rembrandt actually taught his students to invent, not to observe.

-

The evidence in My article “Rembrandt’s Use of Models and Mirrors” proves, beyond reasonable doubt, that these statements are remarkably accurate. The proof of groups of live models in Rembrandt’s studio for the Biblical and other group subjects is incontestable. My recent film on Youtube “Rembrandt’s Adoration of the Shepherds” makes the same point on a grand scale. There we see practically the entire subject matter of two paintings (one seen direct and the other observed from Rembrandt’s same position but reflected in an angled sheet of polished pewter, accurately recorded by Rembrandt even to the extent that the more impressionistic technique suggests the blurred quality of the image reflected in polished metal. Both paintings were once accepted as by Rembrandt). The chances of these very complex space relationships happening by chance, or being constructed by calculation must be millions to one against. There are just too many reversals seen from a different point of view. To suggest, as Prof. E.Van der Wetering does that these were typical exercises in Rembrandt’s atelier is unacceptable lunacy.

This evidence which cuts the ground from under the scholars view is not mentioned let alone discussed in the Getty catalogue. For instance in the penultimate and last paragraph p19-20 explain how Rembrandt’s etching of “The Dismissal of Hagar”1637 “made a great impression on his pupils and inspired many variants….we do not know precisely how drawing from the imagination was handled in Rembrandt’s atelier…..” Yet I, Konstam, have explained precisely how Rembrandt himself developed eleven variants of the same subject from the group of three live models posed in his studio; observing sometimes direct, and sometimes in a mirror to their left and at other times in a mirror behind them, but always from the same seat in his studio. The DVD is available on www.saveRembrandt.org.uk also in the Arts Review Yearbook 1989, not to mention my unpublished book; freely circulated among the Rembrandt establishment many years before.

Peter Schatborn who master-minded the catalogue of The Rembrandthuis exhibition from his position in charge of the prints and drawings at the Rijksmuseum, was also the major contributor of the exhibition at The Getty. He can hardly claim ignorance of my discoveries as he translated my second article into Dutch for inclusion in The Rembrandthuiskroniek in 1978.

The fact is that today’s art theorists seem to have no understanding of the importance of observation in human affairs. It is not enough that scientists are so good at it, their observations are specialized; artistic observation is also specialized but specialized in a different area, an area where neglect is already horrifyingly apparent. By destroying Rembrandt, the figurehead of observed art, the theorists have slued modern art with such success we have to doubt whether it can ever recover. First we must recover The Greater Rembrandt by putting an end to Rembrandt scholarship as it now exists.

Do not burn their books, preserve them as a warning to future generations of experts.

Las Meninas

Las Meninas (1656) is Velasquez’ masterpiece. It is also his most complicated composition but was apparently achieved very quickly without his usual after-thoughts. The paint is remarkably thin, with little over-painting and applied with his usual breadth of handling. Surprisingly out of character for a painter aged fifty six. It needs some explanation. I explained it very simply in an article in The Artist Magazine (Mar 1980) and in a lecture at the Slade at about that time. I also exhibited the model with which I reconstructed the method in the Consort Gallery, Imperial College in that year.

RECONSTRUCTION On the left we see Velasquez at his canvas. A painted self-portrait also often includes the back of the canvas we are looking at, the only difference between this and the usual canvas is that this canvas is very tall. Las Meninas is 10ft, 3.18m tall. A self-portrait requires a mirror. All the other figures appear to be observed in the same mirror. It is surely worth asking the question did Velasquez actually use a mirror. R.Willenski asked that question, and answered yes, but no other art historian seems to have paid the slightest attention. I was initially stimulated to make my own inquiry by reviewing a book “Velasquez. The Art of Painting” devoted to this work, by M.Millner Kahn. Her explanation is so long and tortuous I cannot summarize a whole book.

I agree with Willenski; there are eight good reasons for doing so

1. X-rays show that Velasquez first painted himself as a left-hander and later changed it to conform with reality.

2. He painted the Infanta in the same year but with her parting on the other side of her head. (another mirror reversal)

3. The light comes from the window on the right, it hits the people on the right directly as you would expect but for the Infanta and the people on the left there is also a “fill light” that has bounced off the mirror. See how it illuminates the back of the canvas although the canvas is slanted to receive direct light on the front. Note the cast shadow on the floor.) The mirror is the picture plane between us and the picture. It allows Velasquez to arrange his models within the framed picture space as a photographer might do.

4. All the players look as if they are admiring the Infanta’s reflection in the mirror. The mirror is now at ground level, this may be the first time the Infanta has seen herself in it.

5. The size of the images in the painting are compatible with the idea that Velasquez actually traced their outline on the mirror surface, which he then transferred to his canvas. This would go a long way towards explaining the speed and sureness of the painting’s execution.

6. Velasquez previous work does not suggest an interest in geometric construction or defined interiors, rather the opposite.

7. Until recent times this painting was always exhibited opposite a mirror!

8. Do you see the blob of paint beside the Infanta’s nostril? That confirms the existence of the horizontal support bar we see on the back of the canvas. As the loaded brush hits this ridge it deposits more paint.

Infanta Margarita

I have been looking at Martin Kemp’s explanation of this painting in “The Science of Art” (Yale, 1990) . Kemp draws a ground plan that does not remotely resemble the room we see. It is far too long and narrow (it cannot even contain the width of the canvas he draws). He does not explain the method but tells us that Velasquez’ painting is “a declaration of his supreme gifts as a magician of painterly illusion”. I identified the room as the Pieza Ocbavada, which was more or less square in ground plan (the near ceiling fixture is its real centre; the other fixture is faked.). This room was next door to the Hall of Mirrors. It is no coincidence, in my view, that Velasquez was occupied with the redecoration of the Hall of Mirrors at the time he painted Las Meninas. It seems highly likely that he moved the great mirror next door to save it from possible damage and there conceived the idea of making a picture of the same size to hang opposite it. It may even be that the Infanta and her entourage composed themselves to some extent in front of this marvel (probably the largest composite mirror the world had ever known: over 8ft wide but lost in the fire of 1734)

It is a long established rule in science that the simplest explanation is likely to be the correct one. Why is it that art historians prefer explanations that are so complicated that they have only the vaguest idea of how they could work. Certainly both the hypotheses mentioned above would tie most practicing painters in knots.

My explanation ( Willenski never pursued the idea) could be very useful to a painter who had a complex group portrait to do. There is every reason to believe that both Goya and Velasquez’ assistant knew and used the method as does Ken Howard in our own day.

CREDITING GENIUS WITH THE IMPOSSIBLE obviously appeals to the earthlings longing for the miraculous. Like Velasquez’ “magician’s” achievement here, Kemp’s preferred methods for Brunelleschi’s invention of modern perspective are all beyond explanation, only his least favourite – (f) in his appendix, can produce the goods. This easy acceptance of the miraculous is a consistent failing of Art Historians. Kemp’s preferred solutions show he does not even grasp the problem and therefore cannot recognize the solution. They all put the cart before the horse: the geometry before the image. His scorned solution(f) does work, so would Hockney’s solution but Hockney has not read Manetti.(see “Brunelleschi’s Perspective” in this blog)

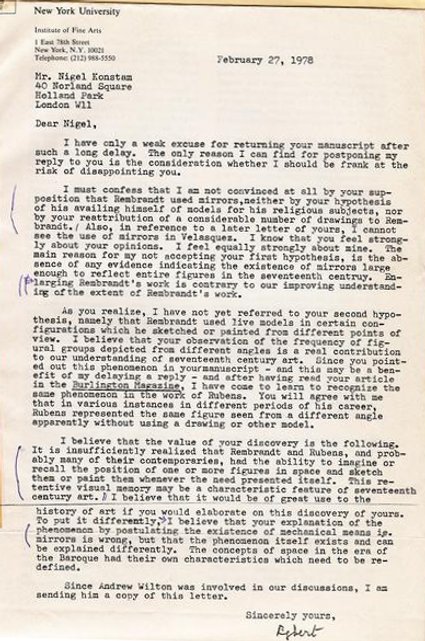

After the publication of my entirely practical explanation of Rembrandt’s quirky production as a draughtsman (Burlington Feb. 1977) which corroborated the reports of Rembrandt’s contemporaries (that he was an inspired observer not an inventor) I visited both Harvard and Yale in search of a publisher for my book on Rembrandt. At Harvard I lectured to the Rembrandt specialists (professors and post-graduate students) The result was a storm of questions. I heard afterwards (at Smith) that the Harvard gang admired my footwork in answering.

AN EXAMPLE

HG “In the 17th c they did not even need still-life in front of them to paint from.”

NK “ What makes you think that”

HG “ Flower painters often painted blooms together that were not in season together”

NK “well flowers wilt, flower painters tend to pick and paint their specimens one at a time”

HG stunned silence.

Although the majority of the audience, I presume, went on to teach and publish on Rembrandt I never received any further communication from any. At the reception afterwards the only people present were myself and the student in charge of the wine. He valiantly tried to convert me to the Harvard view, which has deteriorated still further since then.(see review of the Getty catalogue.)

At Yale I was able to discuss my findings with Prof. Haverkamp Begermann for well over an hour during which time he was unable to advance a single objection to my view. Optimistically I left the typescript of my book with him. After a year, I inquired of it’s progress and it was returned with the accompanying letter which contains the hilarious idea that I had discovered the three dimensional nature of the 17thC imagination! He advised me to write a book about that!

This kind of "thinking" has all but destroyed Rembrandt, the patron saint of the art of observation. Is it not time to wake up to the reality of Art History?

Later, my agents packaged the book on the understanding that it had been accepted by Phaidon with the whole editorial behind it, though they fully understood the revolutionary nature of the contents. All they needed was a reader’s report. When that came they dropped the project and ran. I was given an edited version of the report which made my hair stand on end on the first reading but on closer examination it turned out to be a cunningly crafted swindle. I answered the swindle but to no avail. Word got round and none of the nearly 30 publishers approached after Phaidon found the courage to take on the book but doubtless many experts got a chance for a good look at it. Lawrence Gowing in his review of Svetlana Alpers’ “Rembrandt’s Enterprise” (TLS Dec 16 ‘88) chided “more discussion of the sculptor Nigel Konstam’s observations on Rembrandt’s use of enactments and reflections would not have been out of place”!

Since those days I have done my best to propagate the true Rembrandt with three news-sheets “The Save Rembrandt Campaigner”(to counter the three exhibitions of Rembrandt and his Workshop, in Berlin, Amsterdam and London) with films, shows and DVDs, a website www.saveRembrandt.org.uk and this blog. Most of what I have to say is well within the competence of an educated person. It needs no specialist training in art. All you need is the confidence in your own common sense to see through the bullshit from on high. Our visual culture will be stuck in the mire until some group can muster the momentum to push over the deceitful house-of-cards that is art history. My single voice has all too easily been left to cry in the wilderness.

All these examples can be seen and discussed at

THE MUSEUM OF ARTISTS’ SECRETS.A catalogue of the museum could be of great interest, as also the book on Rembrandt.

Centro d’Arte Verrocchio,

via San Michele 16,

Casole d’Elsa

53031 SI, Italy.

appointments tel.no.0039-0577-948312 or email nkonstam@verrocchio.co.uk

PLEASE PRINT OUT THIS NOTICE FOR THE ART HISTORY NOTICE-BOARD OR OTHER SUITABLE PLACES

For the latest news on Brunelleschi's Perspective and Las Meninas see www.verrocchio.co.uk/nkonstam/blog

Ephebo

This is a secret that has been kept for 2500 years so it is bound to shock.

The great classical tradition of ancient Greece is based on life-casting. I was shocked myself when I discovered this but the proof is beyond dispute as far as I am concerned. It is an unpalatable truth that we must learn to swallow or our culture is founded on a lie.

About the year 500 BC Greek sculpture took a great leap forward, up till that point it had been a provincial imitation of of a culture that had thrived in Egypt for more than 2000 years, reaching its zenith in about 1250 BC in the reigns of Akenaton and Tutunkarmon. The Greeks took the Egyptian tradition a huge step forward towards a more natural pose. The stiffly “at attention” pose gradually softened into the famous Greek contraposto. The Egyptians probably also stood around like this but they never used it in their art. The contraposto so favoured by us was not right for the Egyptians. So it was left to the Greeks to make this break-through. This boy by the sculptor Kritios is the most likely to have been the first. Clearly he is not an athlete, a warrior or a god but an Ephebo, the love object of a homosexual patron, who wanted his boy, to the very life. My guess is that he was first cast in bronze but like 99% of Greek bronzes it was melted down by conquering barbarians to make armaments. This stone version remains more by luck than judgment. It was more valuable as a sculpture than as lime which was all it could have become if destroyed.

This Ephebo may well have been the first body to be cast from life. The drive towards nature was therefore motivated by love.

How can I be so sure? The evidence is very simple. When one models a standing figure in clay one does nothing about the soles of the feet; one cannot see them, no one else will see them. A bronze derived from a clay figure is a hollow shell with no soles (3) but the few surviving life-size bronzes of the classical era all have perfectly formed and naturalistic toes (2) furthermore they are under the pressure of the figures weight. This could only be achieved by the model standing in a pool of fresh plaster (1) When the plaster has set, the rest of the mould is built upon this base. When you think of it the development of Greek sculpture between 500 BC and 450 was far too rapid. It simply is not possible that so many could have reached this perfection so quickly.

These sculptures have become the ideal towards which most figurative sculpture strives. No one has equaled the Greeks. To us casting from life would be considered cheating. For the Greeks it may have been the obvious means of achieving a bronze figure. It would save no end of trouble. They did work over the wax to disguise their method and smarten the result.

Here is the bottom of the foot of one of the Bronzes of Riace. Here is a cast from life that I made myself. I have marked off the hole that would have been cut in the wax to allow the core to be supported. My book will fill in the details and also show the remains of two massive chimneys, one in Athens and the other in Olympia, that I discovered at the same time. The book tells the story of the discoveries.

1.) Modern Life Cast - the model was standing on a ridged tile in a pool of plaster.Note the pressure of the model's weight on the soles of the feet |

2.) Riace - Perfectly formed and naturalistic toes |

3.) Modern - a hollow shell with no soles |

4.) Carved Greek Feet: Pre-life-casting, archaic feet with unnaturally straight small toes and tendons visible when they would normally be sunk in flesh of the foot in this position |

Sculpture the Art and the Practice (2nd edition) ISBN 0-9523568-1-3

I apologize for not answering my critics sooner, I have only just become aware of them. Allow me to explain my point of view more fully on Serota.

Our way of life is changing more rapidly than ever before. Art has to change as life changes. But the white-hot revolution which Harold Wilson (once Prime Minister) foresaw as a great leap forward in opportunities for leisure has in fact put a great deal more stress into human existence; life has speeded up rather than slowed down. Advances in medicine have certainly prolonged life expectancy with the result that the care of the aged now requires far more expense than the pension funds can stand, so pensionable age has to go up. The world population explosion is upon us much sooner than Malthus foresaw. The human population is overwhelming all other species and the planet’s ecology. Climate change etc. etc.

I mention these very real challenges to point out that it is not that easy to predict the future. Yet in art we have allowed Serota with no particular qualifications to dictate the course of art. His “challenging art” does not remotely correspond to life’s challenges as I see them. On the contrary his “cutting edge” is an absurd diversion from what we should be focusing upon.

I see art as an education in seeing what is out there. The more one observes the more one becomes aware of the mental obstacles to seeing. Our survival as a species depends more on the sense of sight than on any other. Serota and his team live in a world of fantasy that does not amuse, it frightens me.

He is a great propagandist but then so were the Nazis, who proclaimed that if you are going to lie, make it a big one. Serota has learnt that lesson well. (see The Jackdaw). He has initiated the most disgraceful episode in the history of art, anywhere. I want to stop him in his tracks. Unfortunately there are a lot of people making a lot of money temporarily out of this financial bubble, so instead of seeing the disgrace, the art establishment is considered a success!

“New Humanism” is my answer to what has gone wrong with art. I respect the Stickists for what they have done to bring about change but I long for a different direction of change, one in which observation figures big again.

Currently there are two theories as to how Brunelleschi arrived at his rules of perspective, which deserve consideration but with which I cannot agree. David Hockney has demonstrated that Brunelleschi could have used a lens to throw the image of the Baptistery onto a surface on which it could then be traced. I could accept this theory if it were not for the evidence of Manetti, a friend of Brunelleschi’s, who had “held the painting (of the Baptistery) in his hands and seen it many times”. I have a second objection to Prof. Martin Kemps preferred theory (he actually lists six possibilities, Hockney’s was published after his book and was therefore not included). The second is that Kemp does not seem to take into account that there were many versions of perspective available at the time; and Brunellschi had to make a second demonstration to persuade people that his was the best.

Giotto and the ancients had a pragmatic means of conveying the space in a building or furniture based on it’s appearance. Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Simone Martini refined this perspective around 1330 so that their complete picture space was logical, and Kemp suggests that this perspective was used by Brunelleschi’s friend, Donatello as late as 1417 in his St. George relief, that is after Brunelleschi had made his first demonstration with the Baptistery. The new perspective did not reach Siena till the 1450s! Clearly the first demonstration was too complicated to follow, or perhaps it smacked too much of wizardry, with its use of two mirrors.

The solution that Kemp least favours I proposed in a lecture at the Slade c1978. (I do not suppose that I was the first to propose it) that is that Brunelleschi’s first demonstration was painted on a “a burnished silver” mirror. Manetti’s description says that “Filippo put burnished silver in the sky” but the reason he gives for this strange behaviour “so that the clouds would be seen to be moved by the winds that blow” seems scarcely credible for a man of Brunelleschi’s scientific bent. It diverts attention from the point he is making. I suggest that the Baptistery and surrounds were painted over the silver but Brunelleschi left the sky unpainted to explain his method.

Brunelleschi had to start from an image of reality that no one could question. The mirror image was such an image. The use of silver as the mirror is easily explained: Brunelleschi was a goldsmith, polished silver was the best reflector available and it had the further advantage over glass that one could scribe on its surface very precisely. The reflective surface could be touched without the thickness of glass intervening. Kemps main objection to this “simple” solution is that ones own image would blot out most of the Baptistery but this is not so. Once one has fixed the eye-point and the mirror one is free to move, to use either eye, and to look through the eye-piece with one’s head at what ever angle is convenient. By this method the size of the blot is no bigger than 2 cm in diameter, that is the distance between the pupil of the eye and the outer skull as reflected. This would not have been the slightest impediment as it need not blot out the outer corners of the Baptistery which are necessary points to fix the image. We can be certain that Brunelleschi would not have gone further with the work before analysing the geometry. The paint would have only been applied to clarify the image for others to appreciate how very like it was to the original. Naturally it needed to be turned round the right way this is why the peep-hole and second mirror were introduced. This method is not only the simplest as Kemp admits, it fits Manetti’s description in all but the one particular. Neither Kemp nor Manetti seem to have understood the need for the second mirror in righting the reversed image traced on the silver mirror.

Kemp’s further objections were:-

-

that Manetti could not have been mistaken in thinking that the silver was applied to the sky area only. But clearly if the rest had been painted over why should he not have made this mistake. On the one occasion on which he held it in his hand we may presume he was preoccupied with seeing the image in the second mirror.

-

Kemp goes on – it does not justify Manetti’s claim for Brunelleschi’s geometry. But it does of course require analytical geometry to arrive at the rules of perspective from the scribed image.

-

The second of Brunelleschi’s demonstrations did not require mirrors; adds Kemp. No, that was why it’s straightforwardness finally convinced the doubters. It was presumably arrived at through the perspective geometry derived from the first demonstration.

(see “A Documentary History of Art vol.I.p171-2 . Anchor books 1957 for Manetti’s whole text in English)